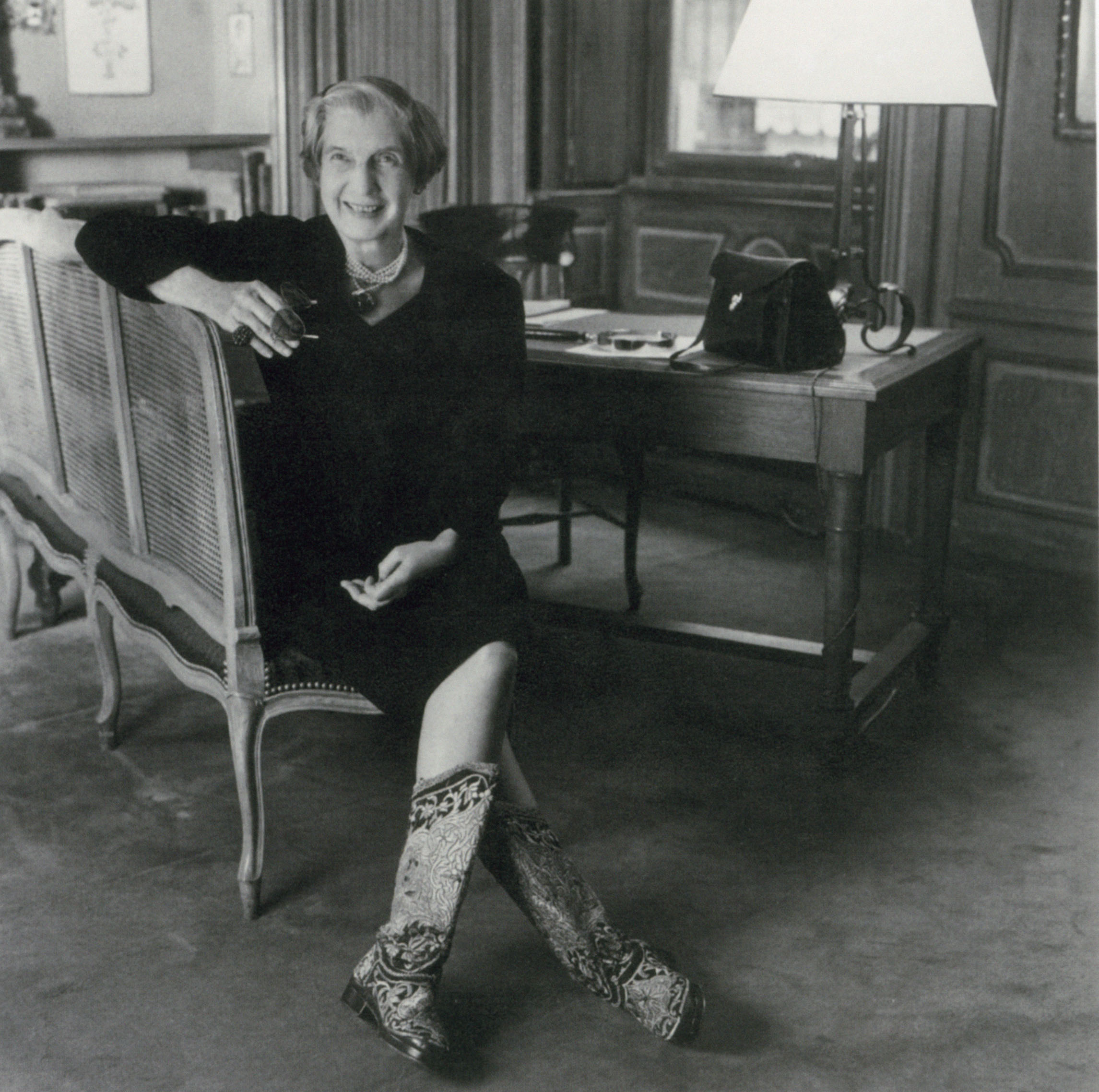

Jeanne Toussaint (1887–1976) was an iconic figure at Cartier. First asked, in the 1920s, to oversee leather goods and, later, accessories, in 1933 she was appointed Creative Director. A woman of elegance and character, Toussaint was nicknamed “the Panther,” and left an indelible mark on twentieth-century jewelry.

A unique background

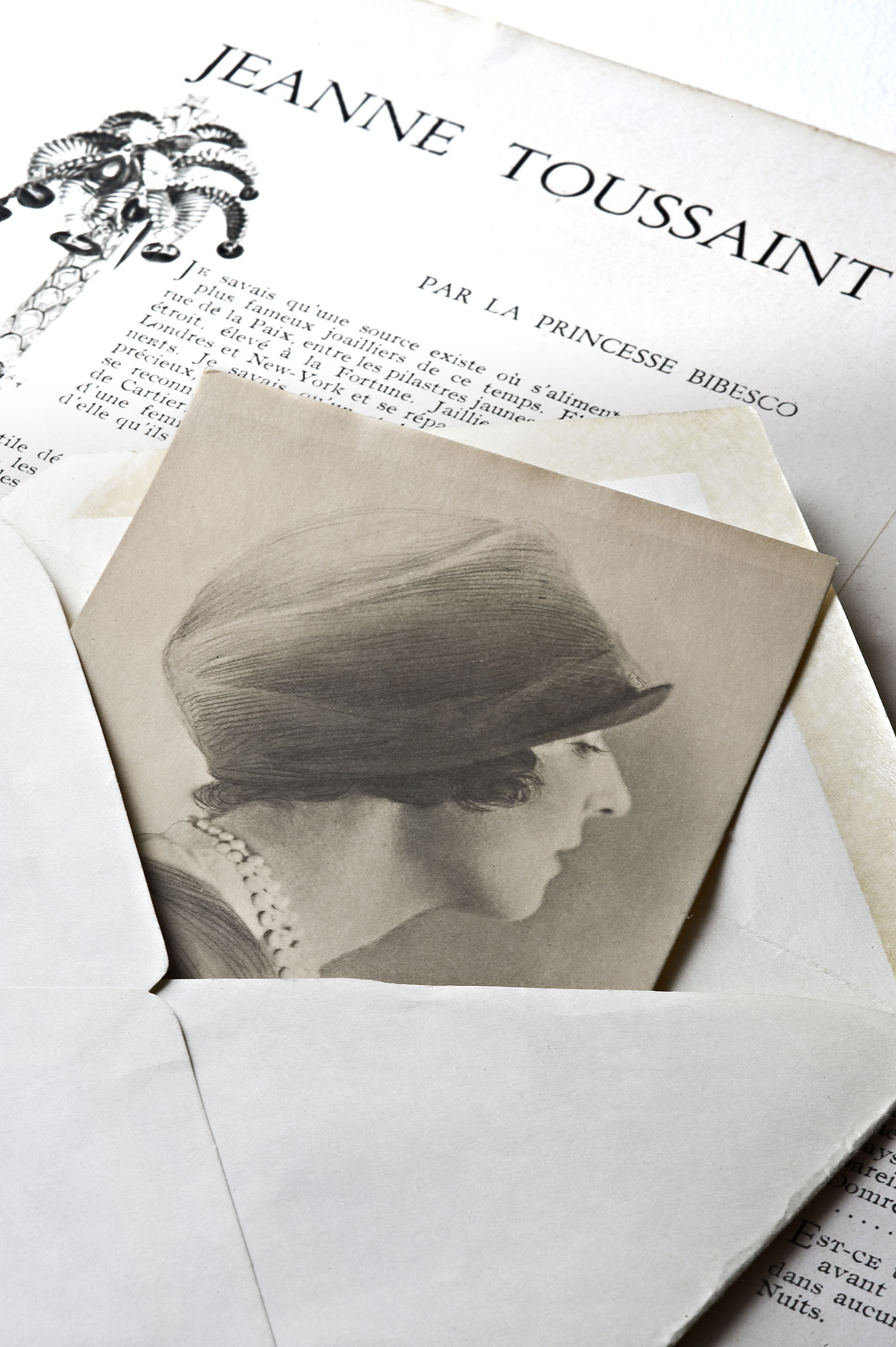

“Who, then, are you, you who perfume diamonds and make lavishness so poetic?” This cryptic question was asked by Princess Bibesco in an article on Jeanne Toussaint published in Le Jardin des Modes in 1948, conveying the mystery surrounding her.

We know little about Jeanne’s youth. She was born in 1887 in Charleroi, Belgium, and apparently attended a parochial school in Brussels as a child before moving to Paris when barely a teenager. There she became a muse to artists and society figures, and even earned a name for herself in the making of women’s accessories.

Toussaint met Louis Cartier in the days of World War I. Intrigued by her sure taste, Cartier asked her to join the Maison in the early 1920s. As she herself recounted, “I began to make handbags. They were a novelty at the time, and were popular.” So popular that in 1925 Louis Cartier made her the head of a new department, named “S” for silver, devoted to the making of accessories at affordable prices.

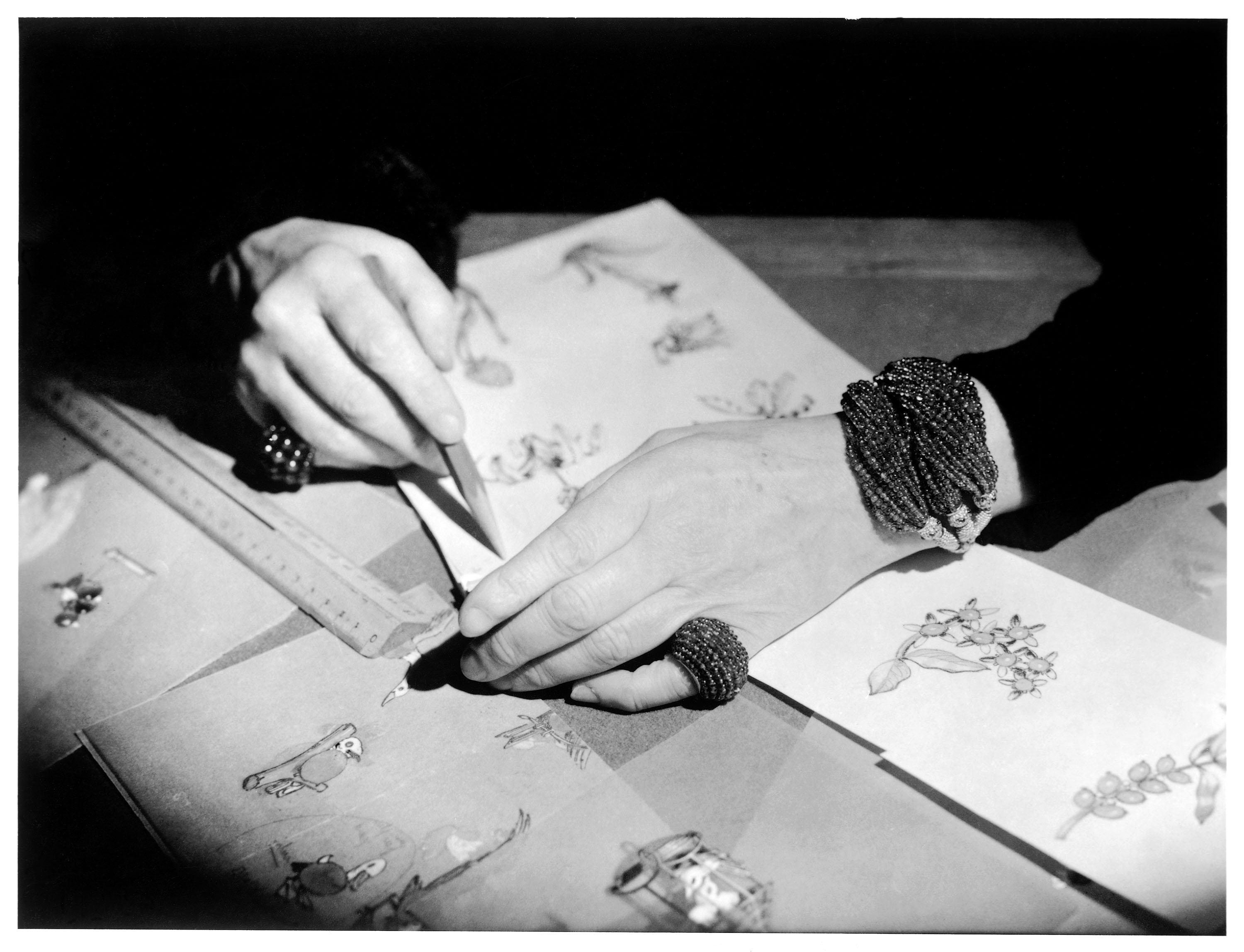

During that same period Toussaint was made a member of the committee that approved all new designs. Alongside “Monsieur Louis,” who chaired the group, she became familiar with the jewelry and timepieces being made by the Maison, as well as its style. This apprenticeship was capped in 1933 by her appointment as Creative Director to succeed Louis Cartier, who was convinced that she shared his vision of style. Spending much of the year in Budapest with his new wife, Countess Almassy, he explained the decision in a letter to his son-in-law: “Since Jeanne Toussaint has excellent, universally appreciated, taste, I am ready to allow designs to be executed . . . under her authority. It is clearly in the company’s interest to make her the artistic director in my absence.” Toussaint remained in that job until she retired in 1970.

The Toussaint sense of taste

As Creative Director of a jewelry and clockmaking Maison, Toussaint was one of the first women to reach that level of responsibility in an almost exclusively male sector. Her personal background, like her independent spirit, alerted her to the need to consolidate this emancipation. Thus under her aegis there emerged jewelry allowing a new emancipation for women.

Her contribution to the field was considerable, extending beyond Cartier’s own walls. As her friend, the French fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy, commented, Toussaint “revolutionized exclusive jewelry by imparting new youth and modernism to it. . . . Therein lies her thoroughly personal style—thoroughly distinctive, thoroughly Cartier.” Even during her lifetime, people referred to the “Toussaint taste.”

One of its main characteristics was the abundant use of noble materials. “Like a great painter [playing with] very fine stones,” as Givenchy put it, Jeanne Toussaint composed her own rich and flamboyant palette. She combined rubies, emeralds, colored sapphires, citrines, topazes, aquamarines, peridots, coral . . . in dense, original combinations, such as pairing amethysts with turquoises or citrines. Cecil Beaton, the arbiter of refinement in his day, wrote in The Glass of Fashion that Toussaint “creates combinations that have hitherto existed only in the jewels from India.” Indeed, inspired by Indian jewelry, Toussaint promoted the much-noted revival of yellow gold just after World War II. Whether smooth, gadrooned, woven, meshed, or even articulated, gold lent character to settings and warmed stones with its sunny aura.

Also worth mentioning are necklaces streaming with emeralds, twisted bracelets, and cocktail rings composed of myriads of ruby and sapphire beads. The flexibility of a jewel always prevailed, in order to allow women easy movement and to encourage a new freedom of attitude. This touches upon the holistic vision associated with Toussaint, who felt that a jewel should always stay close to life itself.

Distant horizons, animals, and flowers

The inspiration behind Toussaint’s creative universe extended to the Far East via Egypt and India. Her taste for distant lands, which she shared with Louis Cartier, was felt on Cartier designs, as notably witnessed by large numbers of “Oriental” pieces. Emblematic motifs from the iconographic repertoires of grand civilizations were conducive to all kinds of designs thanks not just to their visual impact but also their powerful symbolism.

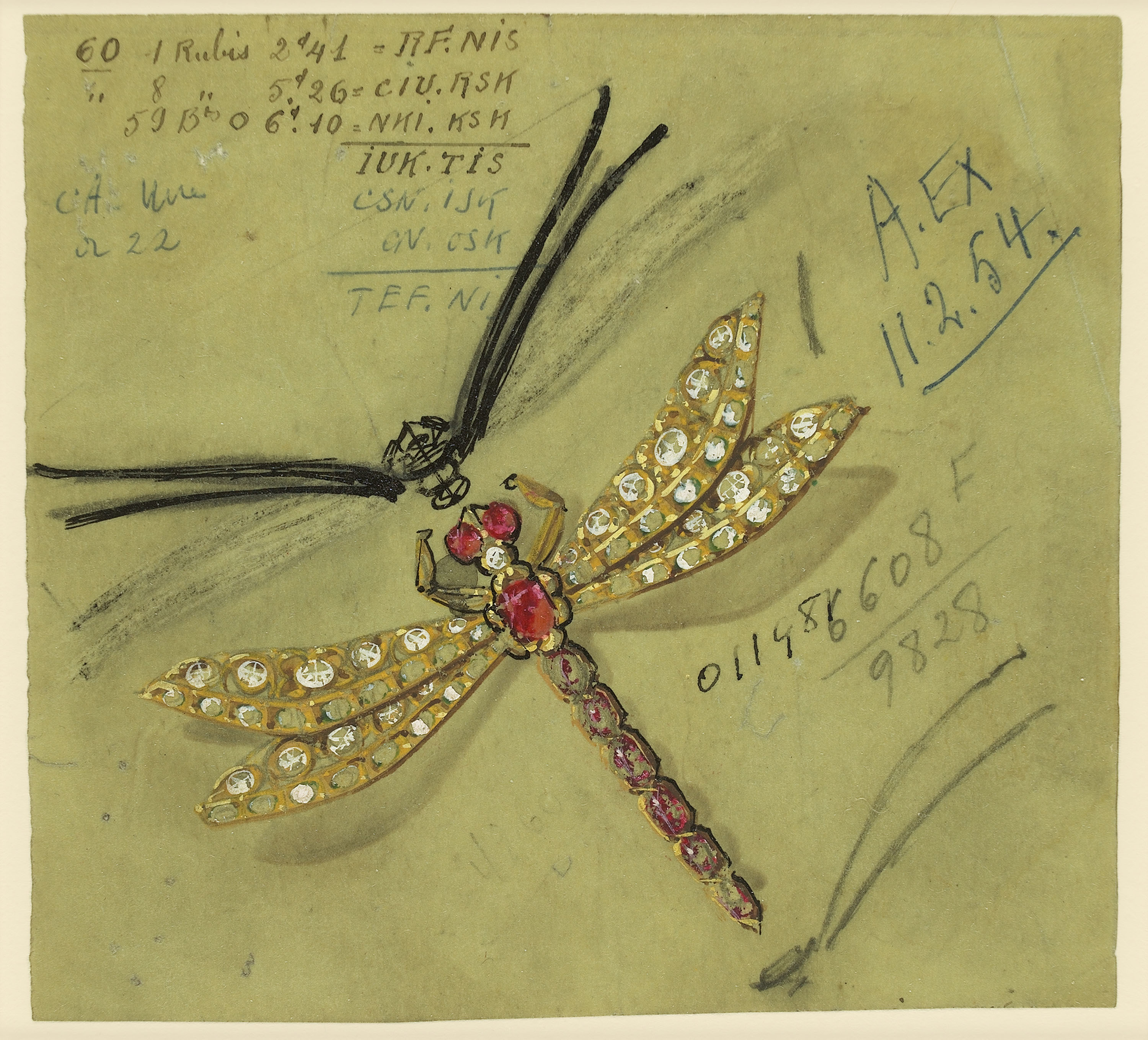

Flora and fauna were another main source of inspiration to Toussaint. Following the Art Deco period and, above all, the end of World War II, she returned to a naturalist vein and challenged designers and artisans to come up with ever more realistic jewelry. The demands of representation led them to reconceive volumes, to adjust lines, and to work precious materials as never before.

Output blossomed. Laurel and palm leaves of fine gold, coffee beans of yellow gold striped and dotted with diamonds, bouquets exploding with color, roses of carved coral, palm trees bursting with precious fruit, unique specimens with lively lines—representational jewelry became a metaphor for a femininity in which sensuality often went hand in hand with a strong character.

When it came to animals, Toussaint added a multitude of creatures to the Cartier bestiary, both real and fantastic. Such was the case, for example, with a lady-bug whose coral body was studded with diamonds. She also brought other animals back into the limelight, such as birds, who had made a discreet appearance at Cartier in the 1920s but multiplied in the 1940s under her aegis. In 1942, when the German army was occupying France, Toussaint even placed highly symbolic brooches of a caged bird in the store window, which earned her a summons to appear before the Gestapo. Once the Liberation came, the patriotic red-white-and-blue bird was freed from its cage.

Of all the animals adopted by Toussaint, however, the one most closely associated with her style is, of course, the panther.

“The panther”

Toussaint was “the panther.” That nickname conveyed both her magnetic charm and her rebellious spirit, her feline allure and her sharp mind. She made the panther her totem in life as well as in jewelry, decorating her apartment with panther and leopard skins. Already in 1917 Louis Cartier had given her a cigarette case decorated with a panther between two cypress trees; two years later she ordered another vanity case, in a striped pattern of gold and black enamel, adorned with the big cat in diamonds, platinum, and onyx.

As Creative Director, Toussaint gave the panther a new, more sculptural look. She imparted volume and life to the cat, encouraging her designers to go to Paris zoos in order to sketch the animal in every pose. In a 1948 brooch for the Duchess of Windsor, she set a yellow-gold cat spotted with black lacquer on a very large emerald, thereby creating the first three-dimensional version of the animal. The following year, another brooch—made for stock—featured a panther proudly set on a sapphire cabochon weighing 152.35 carats. This historic piece was also acquired by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, yet remains forever linked to the name of Jeanne Toussaint.