Art Deco was a broad art movement that emerged in the 1910s and reigned during the following decade. Its aesthetic is characterized by geometric patterns, contrasting colors, and a highly original eclecticism. In the realm of applied arts, Cartier was one of the pioneers of the trend. At Cartier, “Art Deco” was more than a style. It should be understood as an entire, extremely rich period that witnessed the first stirrings of women’s liberation, an unprecedented boom in transportation, and the West’s enthusiastic encounter with the East, all of which were reflected in Cartier designs.

Art Deco before Art Deco: The “Modern” style

Cartier pioneered Art Deco. Right from the early years of the twentieth century, when the neoclassical garland style was still the Maison’s reigning aesthetic, Louis Cartier explored new creative possibilities. He countered the excessive frilliness of the Art Nouveau style with pure geometric forms, boldly simplifying lines and stylizing patterns. He thereby forged a new aesthetic, dubbed “modern,” which laid the foundations for Art Deco.

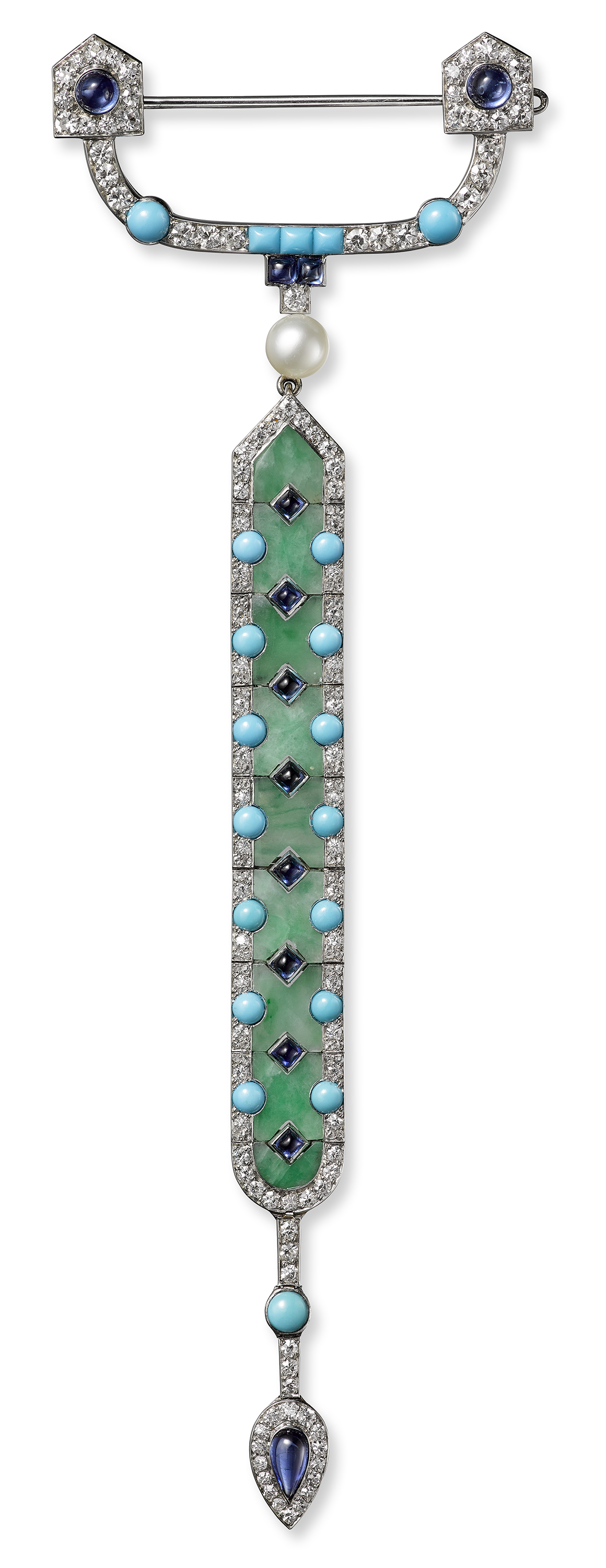

Sober design was enlivened by audacious color. A few chromatic experiments appeared in designers’ sketchbooks as early as 1903, then became more numerous in the following decade, spurred by the Ballets Russes, which began performing in Paris in 1909: the troupe’s “Oriental” aesthetic, with magnificently colorful sets and costumes devised by Leon Bakst, made a big impression on everyone at the time. “Everything is green, blue, red, and orange—that is to say, instinctive, sensual,” wrote a critic obviously struck by the explosion of color on stage. Cartier designers, led by Charles Jacqueau, were not to be outdone, and boldly employed unheard-of color combinations such as blue and violet, orange and green, green and black, black and red, etc. One of the most emblematic pairings, probably of Oriental inspiration, involved blue and green, later called the “peacock” look. Initially thought to be unsuitable, this combination soon became a highly popular Cartier design feature, notably during the Art Deco period.

Another distinguishing Cartier color combination was black and white. This more classical contrast became a popular trend that prefigured Art Deco. Setting diamonds among black enamel or lacquer had already been common during the Victorian era for mourning jewelry, but it returned to fashion in the early 1910s, following the sinking of the Titanic. New York’s high society adopted the look, which Cartier modernized: black introduced a sense of depth and perspective, underscoring shapes and accentuating movement. Also innovative was Cartier’s choice of materials, which often included onyx and even blackened steel, as seen in a tiara made in 1914. Equally characteristic of Cartier jewelry were little touches of color through the addition of rubies or emeralds. But the jeweler became known above all for stylized designs that fully exploited the visual impact of black, anticipating the Art Deco style of the 1920s.

Emancipated jewelry

The 1920s, when Art Deco reached its peak, was a decade of reinvigoration. Following the dark days of World War I, Western countries sought to put the horrors of war behind them in a frenzy of freedom, creativity, and celebrations. Those years became known as the “Roaring Twenties.”

Women were notably instilled with a new spirit of freedom after having replaced their drafted menfolk at the workplace and thereby winning a new social role. Their independence translated into a radical change in dress—corsets were abandoned in favor of full cuts and low waistlines, more conducive to freedom of movement. The look became more fluid, the figure more slender—straight lines became paramount.

This emancipation was reflected in jewelry. As noted by a contemporary commentator in Vogue magazine, “long, feminine, magnificent evening dresses call for matching jewelry that displays the same innovative spirit along with an indispensible air of refinement.” Corsage ornaments, which were too heavy and complicated to be worn on the lighter fabrics coming into fashion, were thus replaced by long necklaces known as sautoirs, underscoring the verticality of a dress. Pendant earrings and brooches lengthened endlessly. The abandonment of evening gloves favored bracelets, whose impact was heightened by wearing several on the same wrist. The less ceremonial jewelry of the 1920s also saw the decline of majestic tiaras in favor of equally alluring but less fussy headbands and aigrettes.

This new style was perfectly incarnated by Cartier designs. The emphasis they had placed on the essence of jewelry in the early years of the century found fuller expression during the Roaring Twenties. House designers finally crossed the line between stylization and total abstraction: recognizable themes and motifs gave way to the visual impact and interplay of abstract forms. Highly architectured designs were structured around combinations of stones, which were cut geometrically—Cartier made early use of the rigorous rectangle and flat top of the baguette cut, for example. As to colors, new combinations perpetuated the experiments begun back around 1910.

A new lifestyle

“Accessories are essential.” Thus declared Vogue magazine in 1929. The liberation of women meant not just a new wardrobe, but a new lifestyle.

As they became more independent, women took up activities and entertainments previously reserved for men, such as driving cars and playing sports. Freer than ever, they henceforth needed to have their indispensable makeup at hand every moment of the day, for every occasion. And they now put it on in public. That explains the profusion of women’s accessories during the Roaring Twenties—not just handbags but compacts, lipsticks, mirrors, and combs, all lodged in clever vanity cases.

Cartier positioned itself in this sector at an early date, as confirmed in the mid-1920s by the launching of its “S” (for “silver”) department. Louis Cartier, assisted by Jeanne Toussaint, developed a wide range of accessories. All displayed the Maison’s emblematic philosophy: never sacrifice usefulness to beauty. All these items were thus as practical as they were beautiful, employing noble materials and a wide range of decorative patterns including the geometric shapes and contrasting colors typical of the Art Deco period.

Men’s accessories were also solidly fashionable in the 1920s, thanks to smokers’ needs and writing implements. The lines of the designs remained clean and refined. The main novelty concerned accessories for travel, which had become a booming new leisure activity.

New horizons

During the 1920s the West opened itself to the world in an unprecedented way. It was an era of trips to the far ends of the earth, thanks to modern methods of transportation—cars, ships, and planes—which made it possible to cross continents faster and more comfortably than ever before.

This “taste for exoticism” influenced Art Deco in every sphere of applied arts, including jewelry, and was often fanciful. But the Cartier brothers were notable for their thorough knowledge of major civilizations; as enlightened connoisseurs and shrewd collectors, they shared their enthusiasm for foreign cultures with their colleagues.

This can be seen, in particular, in items of Egyptian inspiration. The highly publicized discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922 sparked European curiosity about the kingdom of the pharaohs. Cartier revamped the European view of Egypt through designs that betray a conscientious assimilation of Egyptian iconography. Cartier designers, prompted by Louis Cartier as early as the 1910s, not only went regularly to the Louvre to see works but also consulted a library full of scholarly monographs. Their sketches thus employed motifs found on papyri and on architecture. Louis Cartier also encouraged them to use fragments of ancient objects he had bought for the company’s stock of apprêts. The new designs granted a second life to these remnants of Antiquity, set on modern pieces of jewelry, such as a 1925 brooch graced with a statuette of the goddess Sekhmet, supplied by a Paris antique dealer who specialized in Mediterranean antiquities. It displays certain features typical of the Art Deco period, namely a stylized motif (lotus flower), contrasting colors, and the bold use of black enamel.

This enthusiasm for remote civilizations resonated with the blossoming of Cartier’s “modern” style, as notably seen in designs with an Indian feel. The Maison maintained a special relationship with India, especially following Jacques Cartier’s trip there in 1911. During that voyage, he met several maharajahs, some of whom became clients. Despite imperialist clichés to the contrary, Indian potentates were in fact keen on modernity. They were fascinated by Western timepieces and jewelry, and were particularly infatuated with gems set on platinum. Some of them therefore consigned fabulous family jewels to Cartier so that their exceptional gemstones could be re-set in a Western style.

One the first and foremost rulers to place such an order was the maharajah of Patiala. Known for his extravagance and curiosity about technological progress, he was the first Indian to acquire a car and even an airplane. He promoted a Western lifestyle based on his many trips to France, Belgium, and Italy. He also loved European jewelry and timepieces. So from Cartier he bought clocks (including an Egyptian-style one in 1927) and watches (including the Tank he wore on his wrist). In the 1920s he also consigned several thousand gemstones to Cartier, whom he commissioned to make an extraordinary series of items, the key piece being a ceremonial bib necklace completed in 1928. This necklace constituted a significant challenge to the designers and craftsmen, who had to respect the classical forms of Indian jewelry while using platinum settings, and had to employ a uniquely lavish collection of typically Indian stones while incorporating the symmetry and sobriety of the Art Deco aesthetic. By uniting tradition and modernity, Cartier created a link between Indian and European cultures.

The influence was mutual. Indian contributions to Cartier’s own art can notably be detected in the use of carved stones. Ever since the sixteenth century, India has been famous for its gem-carving workshops, originally under the aegis of Mughal emperors. Using a diamond point, artisans etched foliate motifs—and even passages from poetry or the Koran—on emeralds, sapphires, and rubies. On his trip to India in 1911, Jacques Cartier entered into contact with artisans able to supply the jeweler’s workshops, and a decade later he even opened an office in Delhi. Carved stones were initially used singly—such as an emerald set on a brooch, bracelet, or sautoir. Starting in the mid-1920s, however, emeralds, rubies, and sapphires carved with foliate motifs were combined into leafy designs later dubbed Tutti Frutti. These explosions of lavish color represented a new approach that contrasted with the sobriety of Art Deco, even if some items adopted the latter’s symmetrical construction and geometric patterns, notably on the clasps of bracelets.

The arts of Arabia and Persia were also conducive to the aesthetic aspirations of Art Deco. Louis Cartier displayed a precocious interest in Islamic civilizations. Right from the early years of the twentieth century he constituted a rich collection of Persian miniatures of remarkable quality. He spurred his designers to study the Arabic decorative repertoire, from which all representation is often banned in favor of an interplay of lines and shapes, which the designers then interpreted in ways that occasionally neared abstraction. The first sketches of such designs appeared around 1910, increasing in subsequent years thanks to the popularity of the Ballets Russes in Paris theaters. In 1913 there was notably a diamond and platinum pendant in an openwork, streamlined designed that evoked Oriental architecture in a motif that would be employed ten years later for a very Art Deco headband of diamonds. Here, however, the Arabic-Persian inspiration was less detectible, having given way to stylization.

The Far East also had a considerable impact on Cartier in the 1920s. Many designs betray the influence of the Chinese and Japanese iconographic and mythological repertoires, such as vanity cases adorned with dragons or picturesque scenes, not forgetting clocks designed around Oriental architectural features or ancient carved objects. Still other items took greater liberties, playing on the abstract inclinations of ideograms reinterpreted in sober, symmetrical patterns that dovetailed with Art Deco designs.

Art Deco at its height: the 1925 Exhibition

The artistic innovations of this period were epitomized by the “Art Deco Show,” officially known as the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, held in Paris from April to November 1925. The international exhibition was designed to offer a complete overview of contemporary artistry in every sphere. It was this show that spawned the term “Art Deco.”

Divided into pavilions spread over many acres stretching from the Eiffel Tower to the Champs Elysées, the vast exhibition hosted hundreds of creative designers from some twenty countries. Exhibitors were grouped into five main sections, each with several subcategories. Cartier joined the jewelry section, and Louis Cartier served as vice president of the admissions jury of that section, reflecting his influence. He was not convinced, however, that strict adherence to craft distinctions was a good idea. He wanted not just to show his own work among that of his colleagues, not just to vaunt the prowess of modern jewelry, but he aspired to place it in the broader perspective of the fashion of the day. His desire reflected the Cartier philosophy that its designs should participate in a global idea of beauty and refinement. Thus Louis Cartier was also allowed to display his jewelry alongside fashion designers, including Worth and Lanvin, in the exhibition building known as the Pavillon de l’Élégance, whose interior was decorated by Armand-Albert Rateau in an effort to maintain overall coherence while reflecting the image and ambition of each designer. Thus for Cartier he installed sales desks recalling the ones in the Cartier premises on Rue de la Paix.

Cartier exhibited some 150 items of jewelry and clockmaking, all made in the three preceding years. One notable item stood out, namely a spectacular shoulder jewel dubbed “Bérénice” by the leading fashion guide, La Gazette du Bon Ton. It took the form of a platinum band nearly two feet long, divided into several sections that draped over the shoulder with no need for clasp or pin, set with natural pearls and diamonds, and heightened with black enamel. Worn in an unusual, but very feminine and sensual way, this piece was a perfect accompaniment to fashionable dress of the day. It was studded with three old stones, namely Colombian emeralds carved with foliate motifs in the Mughal manner, probably done in India in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. The shoulder jewel was taken apart after the show closed but remains closely associated with memories of the event.

Its streamlined design, Indian inspiration, and elegant drape were all emblematic of the Cartier style during the Art Deco period. The show ended most successfully for Cartier—summing up the general opinion, Vogue reported that “the Cartier display is one of the richest in all kinds of inspired design, as well as one of those where modern art is most clearly expressed.”

White jewelry, or, the decline of Art Deco

The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing worldwide depression triggered the decline of Art Deco, which ended—in terms of jewelry—with “the white trend.” This tendency began with an Arts de la Bijouterie show held a few months before the crash, where pure, serene white was promoted as a reaction to multicolored jewelry.

At Cartier, the white trend meant a return to the sources that had ensured its success at the dawn of the century: the sparkling combination of diamonds and platinum. Designs favored abstract patterns and played on the shapes of stones in sometimes very complicated combinations. They notably exploited the geometry of baguette-cut diamonds, which remained fashionable throughout the 1930s, when Cartier set them not only with other cuts of diamonds, but sometimes with colored stones that underscored effects of light and graphic design.

The end of Art Deco also saw a revival of representational motifs, initially in very streamlined designs. By the late 1920s, stylized foliate motifs were surfacing on Cartier jewelry, such as the tree or palmette found on several brooches. These designs prefigured a return to naturalism, a key theme of the succeeding decades.