Inhabited by a multitude of wild, domestic or fantasy animals, Cartier’s bestiary reveals the richness of the Maison’s style and savoir-faire.

A great diversity of animals

Animals entered the Cartier repertoire very early on, as revealed in registries from the 1860s stored in the archives. They notably mention a bracelet purchased by Princess Mathilde Bonaparte in 1861 decorated with imperial bees. Also listed on her account is a turquoise and diamond brooch depicting a scarab beetle acquired in 1856.

Dragonflies, butterflies and other insects began to inhabit Cartier’s jewelry creations starting in the second half of the nineteenth century. They would continue to populate the Maison’s collections in the following decades, sometimes imbued with symbolic value, as seen by the many scarab beetles in pieces of Egyptian inspiration. The introduction of semi-precious stones expanded the color palette and allowed new effects, capturing the anatomical features of different species. The butterfly clip brooches purchased by the French actress Josette Day in 1945 are one example of this, with the combination of coral, yellow gold and black enamel evoking the subtle colors of this insect. As for the ladybug, bringer of good luck, it witnessed a lively success for ear studs and brooches in the 1930s and following decades.

Birds occupy a high perch in the repertoire of winged animals. The variety of their plumage and the grace of their forms lend themselves perfectly to jewelry, as seen in many pieces from the 1940s and 1950s. Jeanne Toussaint, then Cartier’s Creative Director, encouraged the use of semi-precious stones to depict avian anatomy. Birds of paradise, owls, peacocks and parrots lend their graceful allure and long plumes to lovely brooches. Among the most famous pieces created under Jeanne Toussaint were the patriotic jewelry items symbolizing the oppression of the French people during World War II by means of a caged bird, while a free bird celebrated the Liberation.

Among the wild cats, the panther soon became the most emblematic after its appearance in 1914. It is still an icon of the Maison today. Its cousin the tiger would also receive the jeweler’s honors. Yellow gold, diamonds, black enamel and onyx depict the graphics of its striped pelt while its supple silhouette graces a great range of creations.

Just as predatory, reptiles also bring their strength and sinuous lines to the designs. Salamanders and serpents have been represented in a naturalistic manner on brooches or hat pins since the 1870s. In 1919, a serpent coiled around the neck in a pioneering necklace of platinum and diamonds. Unprecedented at the time, its supple lines embodied the silhouette of the animal with great realism. This shape was reprised in 1997 for the Eternity necklace, enhancing two spectacular emeralds from the Chivor mine in Colombia.

The reptilian theme offered fertile ground for imagination across the decades. In 1975, the crocodile was given pride of place in a necklace commissioned by María Félix. For her, Cartier created a piece of jewelry that is striking for its realism, composed of two fully articulated animals that can be worn together or separately. Since then, the crocodile has been a regular feature of exceptional creations, such as the Orinoco necklace presented in 2014 at the Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris.

Very popular in the 1920s, dragons and chimeras evoke the distant civilizations of the Far East. The complexity of their hybrid anatomy provided a great variety of representations over the decades for jewelry items, timepieces and other precious objects. Emblematic in the Maison’s bestiary, a High Jewelry collection was dedicated to them in 2008.

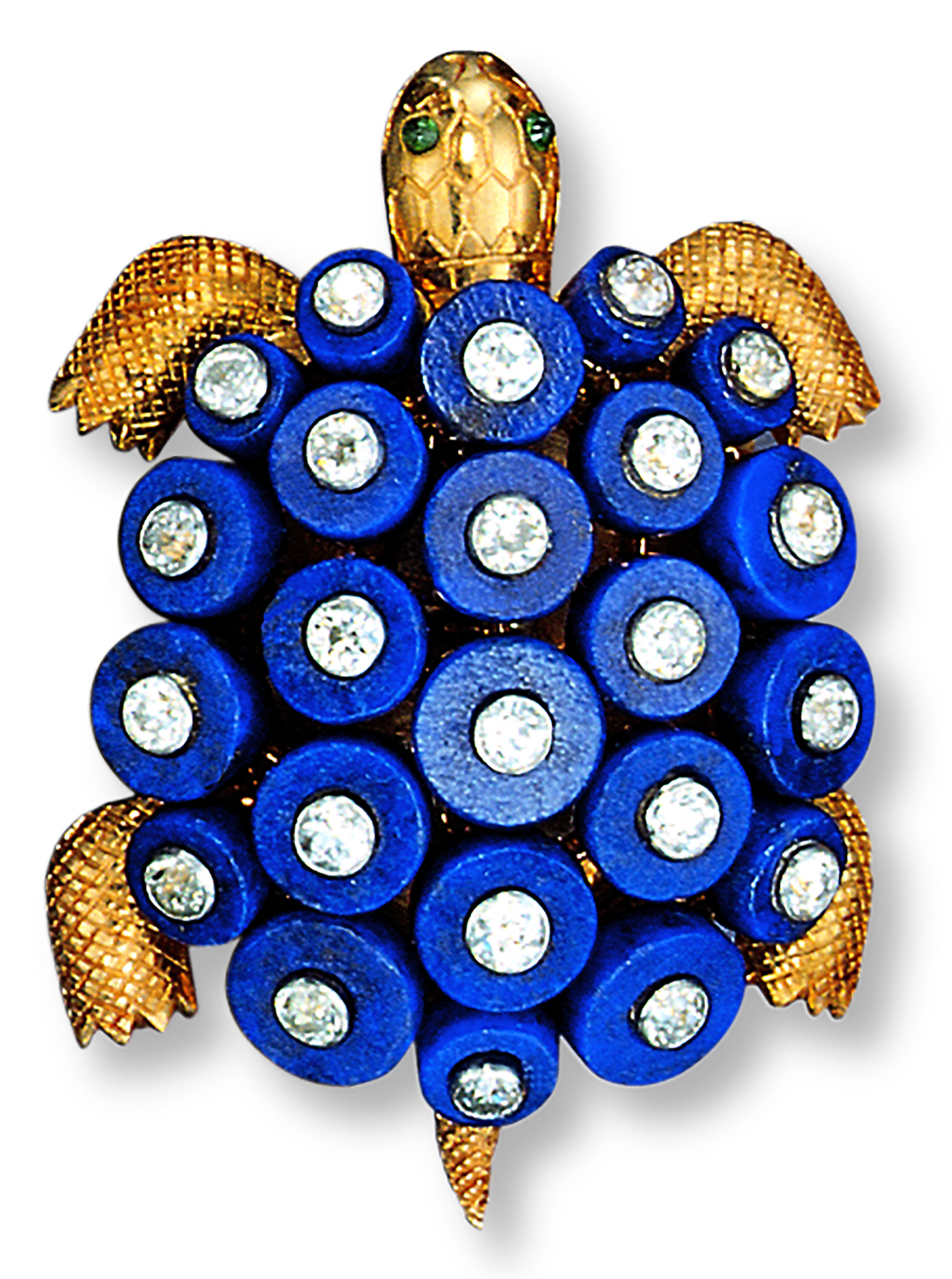

Fish, shellfish and tortoises also have their place in the Maison’s bestiary. Their scales and carapaces are rendered with a wide variety of gemstones. The tortoise stands out: it figures on a number of brooches from the 1930s and is also featured on timepieces.

Cartier’s bestiary explores the most distant horizons. In 2012, the High Jewelry collection paid homage to the polar zones. Families of polar bears and penguins populate, respectively, the chalcedony centerpiece of a necklace and an opal and moonstone brooch.

Savoir-faire at the service of realism

At Cartier, representations of animals are as true as possible to the creatures’ anatomies and behaviors, expressing the desire for realism so dear to the Maison. The Cartier artisans make use of time-honored techniques and develop complex mechanisms to mimic the real animal.

Exclusive to Cartier, the “fur” setting is a technique developed for feline creations. It consists of encircling the stone with miniscule wires of flattened precious metal to imitate the animal’s pelt. It creates an effect bursting with vitality, complemented by spots and stripes in onyx, black lacquer or sapphire.

In order to take the illusion of reality as far as possible, Cartier conceives ingenious mechanisms that appear to bring the animals to life. The wings of a dragonfly brooch created in 1953 are mounted with a tremored setting, each one attached to the body of the insect by a spring, thus allowing the wings to flicker.

The dragonfly looks like it’s about to take flight. Other articulated systems were developed after that, giving some freedom of movement to the animals’ bodies, such as the tiger of the pendant earrings made for Barbara Hutton in 1961. Another example is the snake necklace ordered by María Félix in 1968, a true technical prowess demanding months of work in the Parisian workshops. Its body is composed of individual rings linked via a complex mechanism, giving the necklace a suppleness close to that of the actual animal.

The spread of lost-wax casting at the beginning of the 1980s profoundly enriched the expressive registry of animals. Previously crafted in hammered gold, they could now be sculpted in wax and then cast in the precious metal. This technique made it possible to represent anatomies and postures in a very detailed and precise way, further enhancing the sense of naturalism.

Stylization and abstraction

Parallel to the naturalist vein, the Cartier bestiary has also ventured into stylization and abstraction in increasingly original creations.

Fur and skin are the favorite motifs. Since the nineteenth century, the archives testify to the presence of pieces with reptile scale motifs. In 1914, panther spots joined the Cartier repertoire, followed in subsequent decades by tiger or zebra stripes. At the turn of the new millennium, animal fur was stylized to the point of abstraction: panther spots gradually pixelated into a cascade of gemstones flowing into a prolongation of their bodies on necklaces and bracelets. The composition exploits optical effects to magnify the feline’s vitality and movements. In other, even more abstract creations, the definition of the animal gives way to the graphic power of the design: in a 2013 bracelet, the zebra inspiration is evoked simply by vigorous stripes of onyx that give rhythm to a design vibrating with energy.

Animal bodies offer a large field of expression for the Maison’s artisans. The sinuous bodies of reptiles, the musculature of wild cats or the graceful curves of birds lend themselves perfectly to stylized interpretations. In 1952, a snake was evoked by the suppleness and scale pattern of a gold bracelet. This stylization is also expressed through a greater geometricization of forms, moving toward a more architectural design. Rings with panther or tiger heads, created in the first decade of the new millennium, present very expressive faceted profiles, conceding little to the realism otherwise so dear to Cartier.

Cartier has taken stylization all the way to abstraction. The details of animal anatomy are suggested in daring designs that reveal their aesthetic power through combined effects of form and material. For example, a 2014 bracelet paved with diamonds and sapphires evoking panther spots, is centered around a composition of baguette-cut sapphires creating a wholly novel rendition of the feline’s eye, underlined with black lacquer. Three years later, two timepieces pushed the abstraction even further: one is inspired by the hexagonal motifs on the belly of a snake in a geometrical composition that is as architectural as it is graphic; the other is a chameleon whose roving eye is suggested by a secret watch placed under a rounded-shaped pivoting tourmaline, while its hue-shifting skin is subtly evoked by a mixed palette of tourmalines, turquoise and onyx.

Animals as alter ego

Humans have often likened personality traits and sentiments to the animals around us. These expressions can be found in the Maison’s representations of animals. In the early twentieth century, Cartier began making small sculptures of animals in pietra dura. Dozing pigs, chicks emerging from the egg or huddled together constitute a delicate bestiary of various attitudes.

A few decades later, ducks made an appearance—with a certain sense of irony—for brooches created using a great variety of stones. These birds sport hats, walking sticks and other accessories in a humorous tone. A clip brooch created by Cartier London in 1925 dubbed “The magpie goes to the ball” is a perfect illustration of this mischievous vein.

Parakeets, poodles and other pets entered the Cartier bestiary during the 1950s. These small figurines captured the heart of Princess Grace of Monaco, whose collection was particularly endowed with brooches representing dogs and birds. One of them, a poodle brooch, is notable for the small pearls covering its body to mimic its cottony fur.

Other Cartier clients also fell in love with fetish animals, which became their alter egos. Like Jeanne Toussaint, the Duchess of Windsor is known for her liking of felines, the panther in particular. She purchased two brooches portraying them and later, in 1952, acquired a fully articulated panther bracelet. Barbara Hutton was also quite fond of these animals, her favorite being the tiger, which she sported on earrings, a brooch and a bracelet. Lastly, crocodiles and serpents were the prerogative of María Félix, who collected them in quite a variety of forms.