In the early twentieth century, Russia, famous for its decorative enamel art and the lavishness of the czarist court, constituted an important stage in Cartier’s stylistic odyssey.

Enamel work and sculpted hardstone

Paris, 1900: Fabergé, the jeweler from Saint Petersburg, Russia, was featured at the Universal Exposition held in the French capital, which brought together wonders from the four corners of the earth. In the Russian pavilion, Fabergé exhibited fifteen of its famous enameled Easter eggs. Exposition-goers, who included Louis and Pierre Cartier, were dazzled by the delicate iridescence of the enamel work. Encouraged by their clientele, in the following years they sold accessories and other items decorated with translucent enamel: vanity cases, candy boxes, cigarette cases, perfume bottles, ink stands, travel clocks and other objects became incredibly popular. Cartier’s pieces differed from Fabergé’s in the wider variety of colors employed—in discovering the secret of enamel work, the Maison devised its own palette. Softer hues such as pink, mauve and gray were countered by brighter ones such as red, thistle green and royal blue. These color combinations reflected Louis Cartier’s influence, heralding his bold use of blue and green, which would prove so successful.

The Paris Exposition of 1900 also popularized little animals carved in hardstone, a range of which were produced by Cartier. Among the most popular were owls, storks, ibises, elephants and pigs. This adorable bestiary also made room for bulldogs, spitzes, chicks, parakeets, kingfishers, kangaroos, and penguins. Starting in 1907, the Maison extended its line of sculpted decorative objects to include flowers. Pots of stylized flowers, singly or in bouquets, were placed in crystal display cases. Cartier’s most emblematic flowers were irises, magnolias, hydrangeas and branches of cherry blossoms done in a range of stones notably including agate, pink quartz, aventurine, moonstone and lapis lazuli.

The Maison’s demanding standards of quality meant that it initially commissioned highly reputed Russian artisans to execute these items. Indeed, Pierre Cartier twice traveled to the czarist empire, in 1904 and 1905. The following year, however, a partnership was established with a French workshop to produce the carved animals.

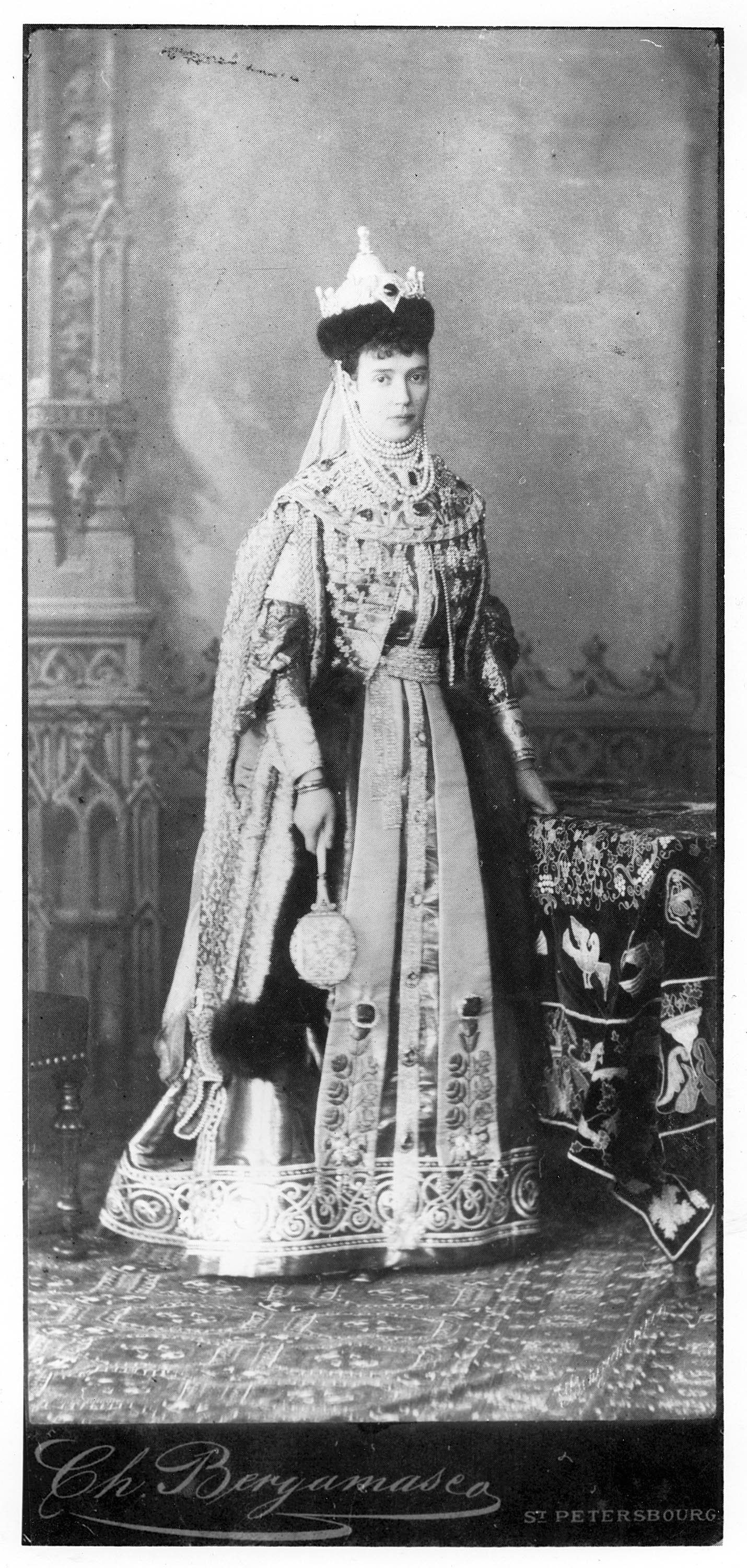

Kokoshnik tiaras

Equally emblematic of the “Russian style,” kokoshnik tiaras deserve their own chapter in Cartier’s history. Inspired by Russian folk headbands in the form of a forward-tilting crescent that crowned the head, they were particularly fashionable in Europe in the early twentieth century. Cartier’s innate sense of balance and clean lines leavened the traditional heaviness of these head ornaments, creating designs that were airy and shimmering, notably thanks to a pioneering use of platinum.

Cartier at the court of the czars

The first visit to Cartier’s boutique by a Russian client dates back to 1860. In subsequent decades, the Maison’s reputation extended to the most eminent aristocratic circles in Russia, including the czar’s imperial court.

In 1888, Grand Duchess Xenia had Cartier bring various items to her palace, and she bought a precious flacon that she gave as a Christmas present to her mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, a great collector of jewels, including famous Romanov sapphire. In subsequent years, the Russian elite would drop into the Maison’s boutique whenever they visited Paris. Company ledgers thus mentioned visits by Grand Duke Alexei in 1899, Grand Duke Paul two years later, and Grand Duchess Xenia in 1906. The books also mention Maria Pavlovna, the wife of Grand Duke Vladimir (son of Czar Alexander II), who presided over Saint Petersburg’s high society. Every winter, in her palace there she hosted grandiose parties for which she regularly ordered new jewelry.

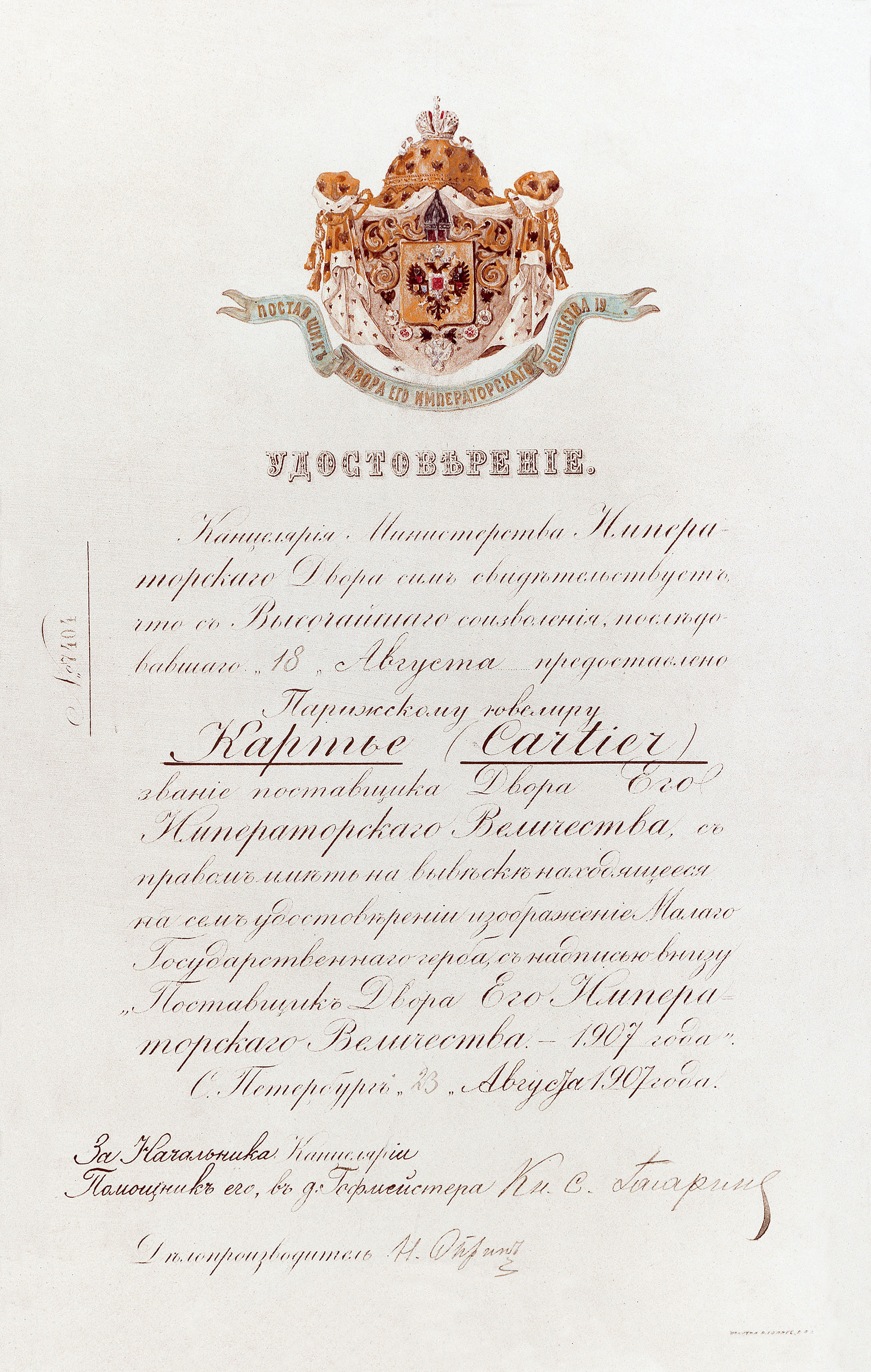

In April 1907, after a habitual sojourn in Biarritz, southern France, Dowager Czarina Maria Feodorovna passed through Paris, where she paid a visit to Cartier. Although she only bought modest gifts, her visit most likely played a decisive role in the history and the establishment of the Maison in Russia. A few months later, in August 1907, Cartier was granted a warrant of official supplier to the imperial court, delivered by Czar Nicholas II, Maria Feodorovna’s son.

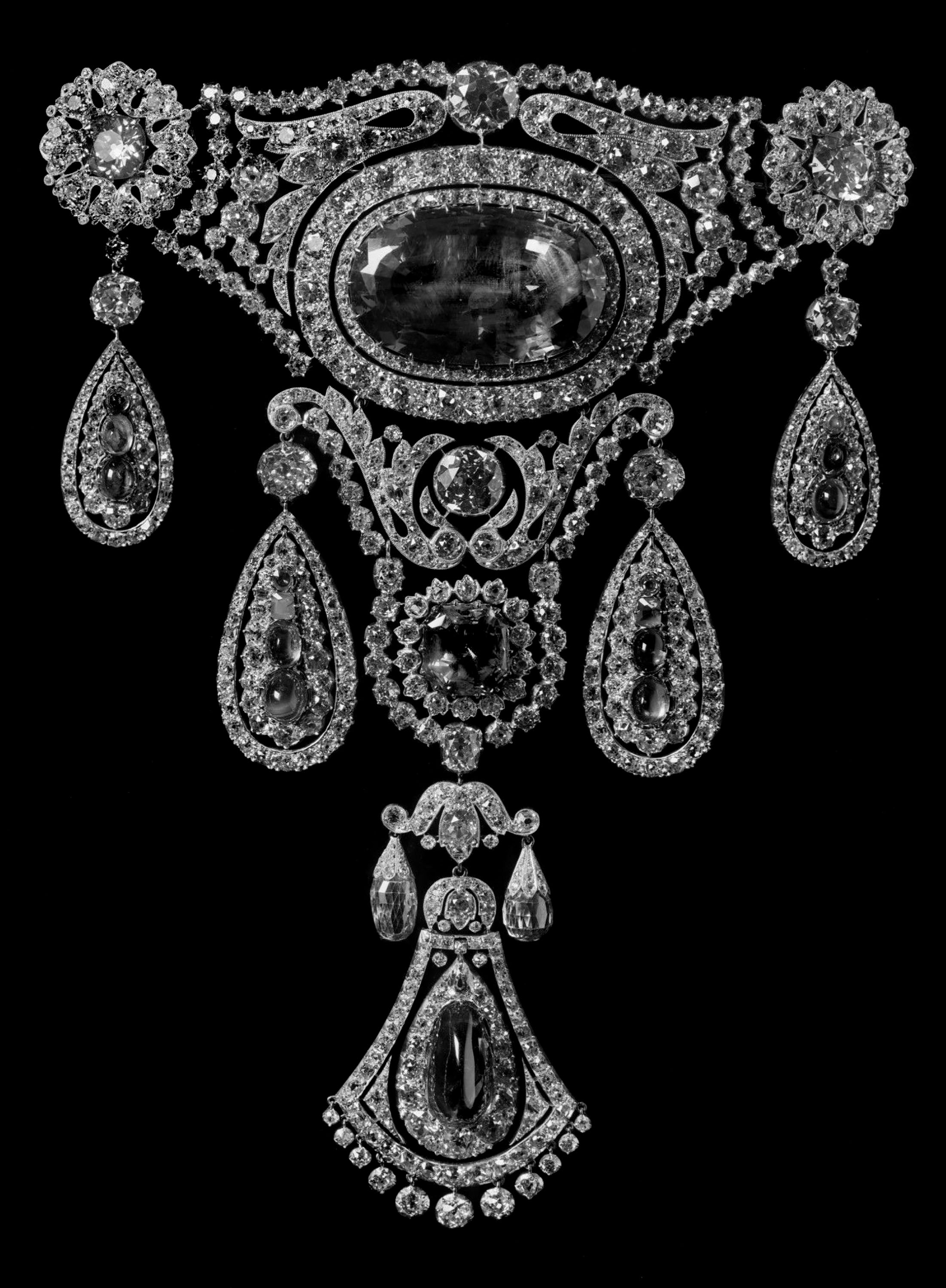

The following year, for Christmas of 1908, the jeweler organized its first Russian exhibition. Installed in a mansion on the quay of the Neva River, made available by Maria Pavlovna, the temporary boutique displayed a selection of platinum and pavé-set diamond brooches, diamond or ruby necklaces, corsage ornaments, Greek-key patterned tiaras, watches and clocks. No fewer than 562 written invitations were dispatched to the leading members of the Saint Petersburg elite.

In the years that followed, from 1909 to 1914, Cartier regularly organized sales exhibitions in Saint Petersburg, often at Easter or Christmas and usually at the Grand Hôtel Europe. Louis Cartier himself would also start traveling to Russia as of the 1910s. Russian clients showed up at each of these events, while others continued to visit the Rue de la Paix boutique during trips to Paris, notably Countess Sherbatov and Princess Lobanov.

Henceforth, well-placed within the imperial court, Cartier received increasingly magnificent orders. For example, in 1909, Maria Feodorovna commissioned the making of a tiara for which she supplied a 137.2-carat sapphire, followed a few months later by the purchase of a corsage ornament that featured an even larger sapphire weighing 162.24 carats. Three years later, Grand Duke Cyril, seeking a Christmas present for his wife, bought a sautoir (or long necklace) from which hung a star sapphire weighing a spectacular 311.33 carats. In 1914, Prince Yusupov purchased a tiara for his fiancée, Irina, whose family was said to be even wealthier than the Romanov dynasty.

In those days, Cartier could be considered the most “Russian” of French jewelers. Thus in 1912 the Paris city council, which wished to give Czar Nicholas II a gift that would symbolize the special relationship between the French capital and the Russian court, turned to the Maison, which proposed a sublime Easter egg. Made in purple and white enamel, adorned with the czar’s monogram, the egg opened to reveal a photograph of the czar’s young son, the czarevich. This marvel of refinement is now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, demonstrating that Cartier was thereafter the equal of Fabergé.

The First World War and the Russian revolution of 1917 put an end to the lavish czarist court and, by extension, to Cartier’s activities in Russia. The Russian aristocracy, exiled to western Europe—notably France—approached Cartier in order to negotiate the sale of its jewels. Loyal toward its former clients, the Maison bought some of them back, such as the Maria Pavlovna emeralds, which would be used in a set of jewelry made for Barbara Hutton. Cartier also acted as a go-between for the Yusupovs, notably concerning the sale of their famous Polar Star diamond.