The American branch took root in New York in 1909 under the leadership of Pierre Cartier (1878–1964). The showrooms were initially located at 712 Fifth Avenue, until a mansion on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street was bought in 1917. The mansion at 653 Fifth Avenue, owned by Morton and Maisie Plant, was acquired in exchange for a two-strand natural pearl necklace. Cartier opened its new premises there in October of that year.

Initial contacts with American clients (pre-1909)

Although the New York branch did not officially open until July 1909, links between Cartier and American customers went back a long way. As early as 1853 Louis-François Cartier (1819–1904) received his first American client in Paris. In 1855, the jeweler’s account ledgers listed two new clients, both from New York.

While the existence of an American clientele might at first seem marginal, it became much less so once Cartier moved its store to Rue de la Paix in 1899: the likes of J. P. Morgan, Cornelius and W. K. Vanderbilt, and Madames Townsend, Astor and Whitney suddenly appear in the order books. Some of them resided in Paris—such as Mrs. W. K. Vanderbilt, who lived first on the Champs-Elysées and later on Rue Leroux, but many were just passing through the capital. So opening an American branch soon seemed an obvious move.

Early days (1909–1917)

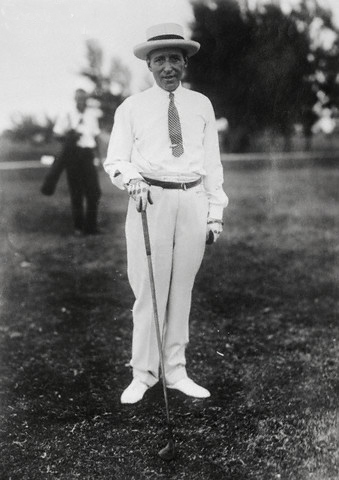

It is hard to say exactly when Pierre Cartier went to the United States for the first time. But the fact that he left the running of the London branch entirely to his brother Jacques (1884–1941) in 1906 suggests that the question of a transatlantic branch was already being explored. Opening a New York store was probably planned earlier, but the financial panic of 1907 hit New York bankers hard, and put a halt to the project.

When it came to looking for sales premises in 1908, Alfred Cartier (1841–1925) made the trip in person. He was sixty-seven when he crossed the Atlantic on the Océane, accompanied by René Prieur, secretary to his eldest son Louis (1875–1942). Alfred fell for a building that he described as “very French in appearance, being Louis-XVI style in dressed stone.” It was on the fourth floor of this building, at 712 Fifth Avenue, that Alfred decided to set up his New York offices.

Prudently, he did not open a whole boutique but just “one or two elegant salons, plus a repair workshop.” The American branch officially opened in July 1909, headed by Pierre Cartier, who was assisted by a sales manager, two salespeople, a head of workshop and a team of stonesetters.

The Cartier Mansion (1917)

Success was instant. Major transactions such as the sale of the Hope diamond established Cartier’s reputation in America. Given that situation, it soon became necessary to find new premises that would embody the Cartier image. As early as 1912 correspondence from New York mentioned the search for a “Cartier building.” It was not until 1917 that Pierre Cartier fell in love with a Renaissance-style mansion on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street.

Built in 1905 by architect Robert Gibson for banker Morton Plant, the building occupied a strategic plot in the Vanderbilts’ former preserve. A keen negotiator, Pierre acquired the property in exchange for a necklace of two strands of natural pearls (fifty-five and seventy pearls, respectively), valued at one million dollars and coveted by Morton Plant’s wife, Maisie. After a brief period of renovation, the new Cartier showroom welcomed its first clients in October 1917.

Workshops and creative design

Although grand items of jewelry were initially dispatched from Paris, the distance created obvious logistical problems. Furthermore, customs duties made the importation of finished jewels prohibitively expensive. That is probably why the New York offices had a small workshop right from the start, largely composed of stonesetters. Sketches, plaster models, and incomplete settings could be sent from Paris to New York, where the jewelry would be finished.

The original small workshop swiftly grew. By 1910 it boasted forty-five employees, including “a workshop manager, thirty workers, four polishers, eight setters, and a clockmaker.” Another sign of growth was the design team, which expanded very quickly. Thus Alexandre Genaille, who got his start in Paris, moved to New York right in 1909. He was joined by Maurice Duvallet in 1911, by Émile Faure in 1912, and by his own brother, George Genaille, in 1914.

In fact, the design studio remained a purely French affair until the arrival of American designer Alfred Durante in the 1950s. It was Durante who designed the emblematic New York pieces of the 1960s and 1970s, notably a necklace made for Elizabeth Taylor in 1972, featuring a pearl known as the Peregrina.

As to production of jewelry, it was not until the acquisition of the building at 653 Fifth Avenue that the New York branch had a substantial workshop.

Located on the fifth floor of the premises, American Art Works counted as many as seventy employees, supervised by Paul Duru; and in 1925 a second workshop opened, called Marel Works.

Although Cartier’s exclusive jewelry is all designed and made in Paris these days, the Fifth Avenue building still maintains a small workshop.

Famous clients and stunning sales

Right from the early years, the order books of Cartier New York included the glamorous names of Astor, Vanderbilt and Rockefeller. The people who largely contributed to the success of the Paris firm indeed remained loyal to Cartier after it moved across the Atlantic.

At that time, a large number of clients came from the banking and industrial sectors. Among the most constant was Mrs. Stotesbury (1865–1946), who had already made major purchases in Paris in the 1910s. Originally from Chicago, she lived in Philadelphia with her husband Edward Townsend Stotesbury, a banker close to J. P. Morgan, and she notably took a special interest in pearls and emeralds.

Another major buyer was Marjorie Merriweather Post (1887–1973), heiress to the Postum Cereal Company and founder of General Foods. The long list of her purchases reveals a veritable passion for jewelry, especially items with historic interest. In 1928 she had Cartier New York re-set diamond earrings that once belonged to Queen Marie-Antoinette. That same year, Post had a pendant of platinum, emeralds and diamonds—made in London in 1922—turned into a large shoulder brooch. Composed of seven Mughal emeralds dating from the seventeenth century, this brooch can now be seen at the Hillwood Museum outside Washington, D.C.

Having rapidly understood the importance of publicity for succeeding in the New World, Pierre Cartier became noted for his highly newsworthy sales. In a masterstroke, he managed to sell the Hope diamond to Evalyn Walsh McLean (1886–1947). Mrs. McLean, the daughter of a gold prospector and the wife of the heir to the Washington Post newspaper, had a colossal fortune and had just bought the Star of the East, a 94.80-carat pear-shaped diamond, from Cartier Paris in 1908. Then she fell for the famous blue Hope diamond, which was discovered by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier in 1669.

Nearly half a century later, the sale in New York of another extraordinary gem made the headlines. In 1969, Cartier outbid Richard Burton at the auction of a 69.42-carat pear-shaped diamond—it was the first time a diamond broke the symbolic record of one million dollars. Four days later, Cartier and Burton came to a deal: the jeweler agreed to sell the stone to the actor in exchange for the right to display it at its premises in New York and Chicago. In a matter of days, over six thousand people thronged to view the Taylor-Burton diamond on show in the Cartier Mansion. At the same moment, the Cartier workshop was making the necklace that Burton would give Elizabeth Taylor as a present.

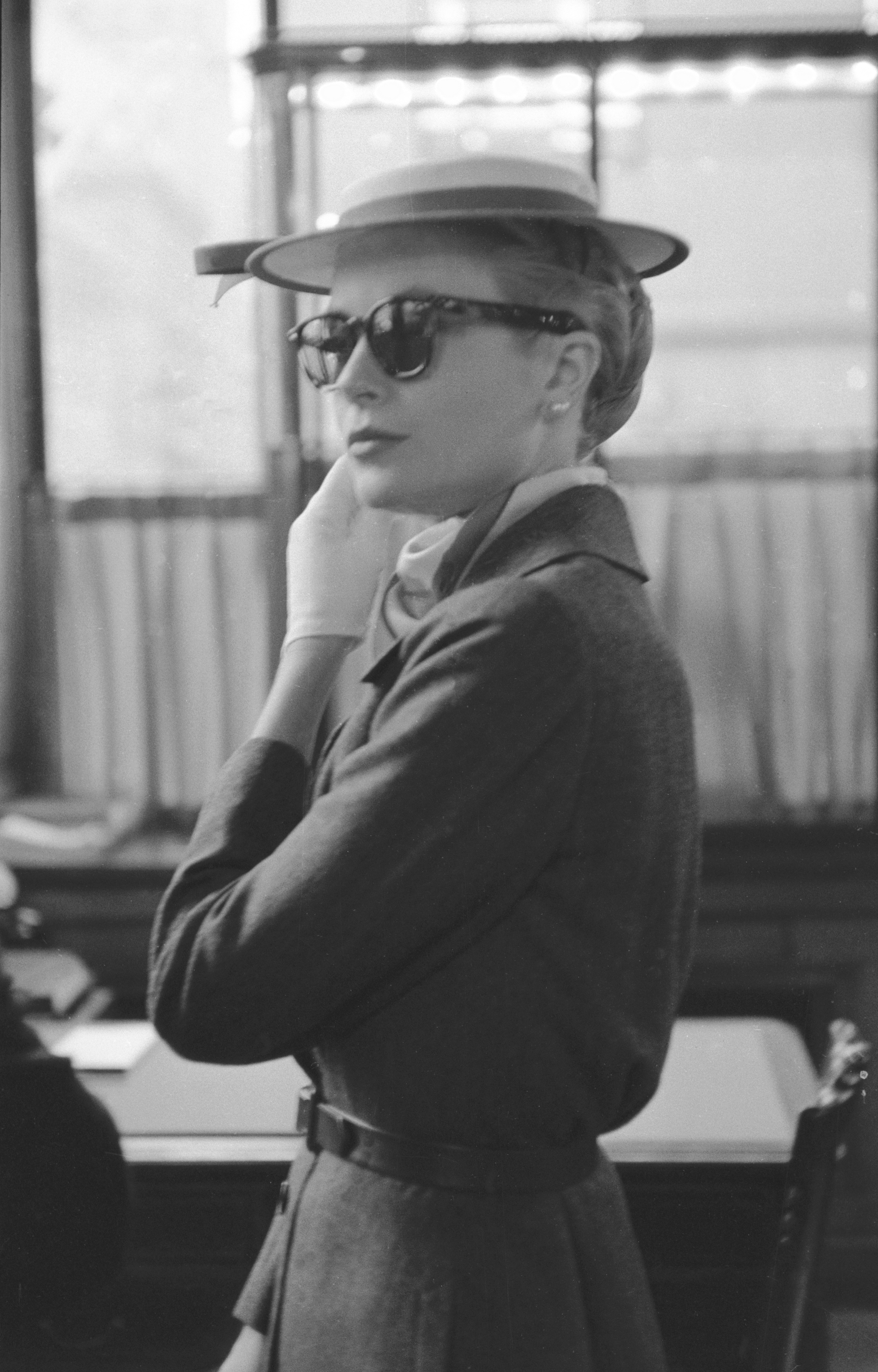

Hollywood clients have played a special role in Cartier’s history, as exemplified by jewels made for the likes of Elizabeth Taylor (1932–2011), Gloria Swanson (1899–1983) and Grace Kelly (1929–1982). Cartier and its famous “little red box” became a landmark of the movies. Scenes from several films were set in the Fifth Avenue boutique, such as Star! (1968) with Julie Andrews. And Mia Farrow was draped in Cartier jewelry when acting opposite Robert Redford in the film adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby (1974). Great names from Broadway were also loyal Cartier clients, from Fred Astaire (1899–1987) to Irving Berlin (1888–1989), whose purchases displayed a pronounced taste for emeralds, and Cole Porter (1891–1964), who gave his wife Linda Lee Porter splendid Tutti Frutti jewelry.

People: Pierre Cartier, Jules Glaenzer and others

The American branch was headed from 1909 to 1947 by Pierre Cartier (1878–1964), grandson of the founder. In 1908 Pierre had married an American woman from Saint Louis, Elma Rumsey, and became highly integrated into New York society. He adopted the pace of life of his American clientele and their seasonal migrations. He was thus in the right place at the right time. He went to Florida in the winter and spent most of his summers in France. As an accomplished businessman, he was aware of the importance of modern techniques of promotion in the New World.

Aware that he was representing the interests of a French firm on a distant continent, Pierre assumed an authentically political role as a representative of France abroad. He became vice president of the Alliance Française in New York, served as president of the French Chamber of Commerce from 1935 to 1945, and was president of the Franco-American committee for the international exposition in Paris in 1937, to mention just of a few of his offices. This political role was crucially important, notably enabling him insure good coverage for Cartier at the world’s fair hosted by New York in 1939.

Right from the early years Pierre surrounded himself with men he could trust, and who directly contributed to the success of the American branch. Most were French, and most had earned their stripes in Paris. That was the case of Paul Muffat, who became sales manager in New York in 1910. Muffat began his career in Paris, and participated in the second temporary exhibition held in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1908. He would return to Paris in the 1920s, going on to run the Saint-Moritz boutique in 1937.

Another crucial player was Jules Glaenzer (1884–1977), who joined Pierre Cartier in New York in 1910, becoming the key salesman of the Fifth Avenue boutique. Of French and American stock, Glaenzer cut a good figure in New York society and was on familiar terms with the leading names on Broadway and in Hollywood. Having begun his career as a salesman in Paris in 1907, he would rise to vice president of Cartier New York in 1927, then to chairman of the board in 1963, finally retiring in New York in 1966.

In 1947, Pierre Cartier sold the American subsidiary to Claude Cartier (1925–1975), Louis Cartier’s son. Claude headed the subsidiary until it was sold in 1962. The American operation was subsequently managed by various groups of investors until it was bought by Robert Hocq in 1976.

Cartier New York today

The New York branch gave birth to two leading creations in 1969 and 1971, when Italian designer Aldo Cipullo came up with the Love and Clou (Nail) bracelets, now two Cartier icons.

In 2009 Cartier New York celebrated its centenary with an exhibition at the Museum of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. Titled Cartier and America, the show recounted the story of a century of Cartier’s relations with its American clientele. Several major museums have also exhibited the Cartier Collection in the United States. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York organized the first major retrospective, titled Cartier 1900–1939, hosted first at the Met in 1997 and then at the Field Museum in Chicago in 1999. In 2005 Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts presented Cartier Design Viewed by Ettore Sottsass, while more recently, in 2014, Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art held Brilliant: Cartier in the 20th Century.

Indisputably, Cartier has now become a fully integrated feature of American culture. Two first ladies have chosen to pose with Cartier watches on their wrists: Jackie Kennedy, who constantly wore her Tank watch, was followed by Michele Obama, photographed in 2009 sporting a Tank Française for her official White House portrait.

In 2016, the premises at 653 Fifth Avenue underwent major renovation. The legendary New York boutique thus reopened bright and shiny to celebrate its centenary in 2017.