Jade, an age-old semiprecious stone, was a prized substance in the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Americas as well as in China. In Western jewelry, jade came to the fore during the Art Deco period, although Cartier had begun using it in the late nineteenth century. In the 1920s, Cartier devised highly original designs around old jade from its stock of apprêts (trimmings or fragments of ancient decorative items). During that same period, jade was one of the stones that Cartier liked to combine with rubies, coral, sapphires or even onyx to create bold color compositions.

Properties

In fact, “jade” is two distinct minerals: jadeite and nephrite. Both are extremely hard—jadeite is 7 on the Mohs scale, nephrite is rated 6–6.5—and thus must be worked with suitable abrasives, saws, drills, and mills. When worked traditionally using these manual tools, jade requires much time and patience from an artisan, imparting all the more value and esteem to these creations.

A varied range of colors

Depending on the elements composing it, jadeite can occur in a wide range of hues—white, pink, brown, red, orange, black, mauve, blue, purple. If chrome is present, jadeite will take on an almost emerald-green color, one of the most desirable, and is called jadeite jade. The necklace for which Barbara Hutton asked Cartier in 1934 to design a ruby-and-diamond clasp, is one of the most precious examples: its twenty-seven beads of jadeite, of an intense green and outstanding quality, all came from the same block of stone. Hutton, an American heiress who was a great collector of Cartier jewelry, seemed to appreciate the stone and this color combination.

According to the Maison archives, her account during that period listed a large number of designs playing on this bichromatic effect: they included, among others, a ring set with a 37.67-carat jade cabochon surrounded by buff-top and caliber-cut rubies, ordered the same year as the necklace, and—the previous year—a bracelet composed of four strings of beads punctuated by two components of platinum, diamonds and rubies.

Nephrite also comes in a rich variety of colors, often veined, ranging from green to reddish brown via white, yellow, gray and blue. One of the most sought-after colors is white, called “mutton fat.” It can be seen, for example, on a plaque of carved white jade used as the dial of a large clock made in 1926, described as a “Screen” clock in the archives, and today part of the Cartier Collection.

Main sources

The main deposits of nephrite are found in Xianjiang (China) and Siberia, and also in Switzerland, New Zealand, Australia, Poland, Italy, Silesia, the United States, Canada and Brazil. Major deposits of jadeite were found, starting in the eighteenth century, in Burma, then later in the Yunnan region of China and in California and Guatemala.

Symbolism

In China, jade—whether jadeite or nephrite—is considered the most precious of gems. Right from the Neolithic period, Chinese tombs contained ceremonial weapons and religious objects whose meaning and precise use are no longer known. Shrouds composed of small plaques and tubes of jade sometimes entirely cover the body of the deceased, giving rise to the expression, “buried in jade.” Indeed, in Chinese culture jade has an aura unmatched by any other precious material. It is first of all ascribed with prophylactic qualities, even preventing bodies of the dead from decomposing, which would explain its presence in graves.

Crushed into a powder, jade was reputed to lengthen the life of the monarchs who ingested it. This tradition is reflected in certain pieces of Cartier jewelry: a pair of pendant earrings made in New York in 1926 and now in the Cartier Collection is composed of two jade disks flanking a stylized motif in red enamel that recalls the shu ideogram, meaning “long life,” and thus offering its owner a double promise of immortality.

In addition to such beliefs, jade embodied moral virtues associated with Confucianism, such as benevolence, wisdom, moral uprightness, modesty and loyalty, so that anyone who owned jade would be the better for it.

Cartier and jade

In the West, the use of jade in jewelry became widespread during the Art Deco period. Cartier’s use of it can nevertheless be traced back to the late nineteenth century—one of the stock ledgers still in the Maison’s archives lists a “jade bottle, gold mount, pink enamel stopper,” dated 1898. An art dealer, Bing, is mentioned as the supplier of the bottle. During the first decade of the twentieth century, many plaques of carved jade were listed. They were worked by Cartier, who mounted them, along with gemstones, on a setting of precious metal—at which point they were often placed at the tip of a pendant.

The 1920s were the heyday of such Asia-inspired designs in which an article of jade was set in a contemporary piece devised by Cartier’s designers, for timepieces and accessories as well as jewelry. When it served as the main feature, jade was almost always associated with designs of Chinese inspiration, although exceptions occurred, such as a Mughal-style necklace featuring a pendant of white jade from India, carved on one side and set with carved rubies and emeralds on the other. When jade was not the main component of a design, it was often used on little animal brooches to depict the creature’s body.

Color combinations

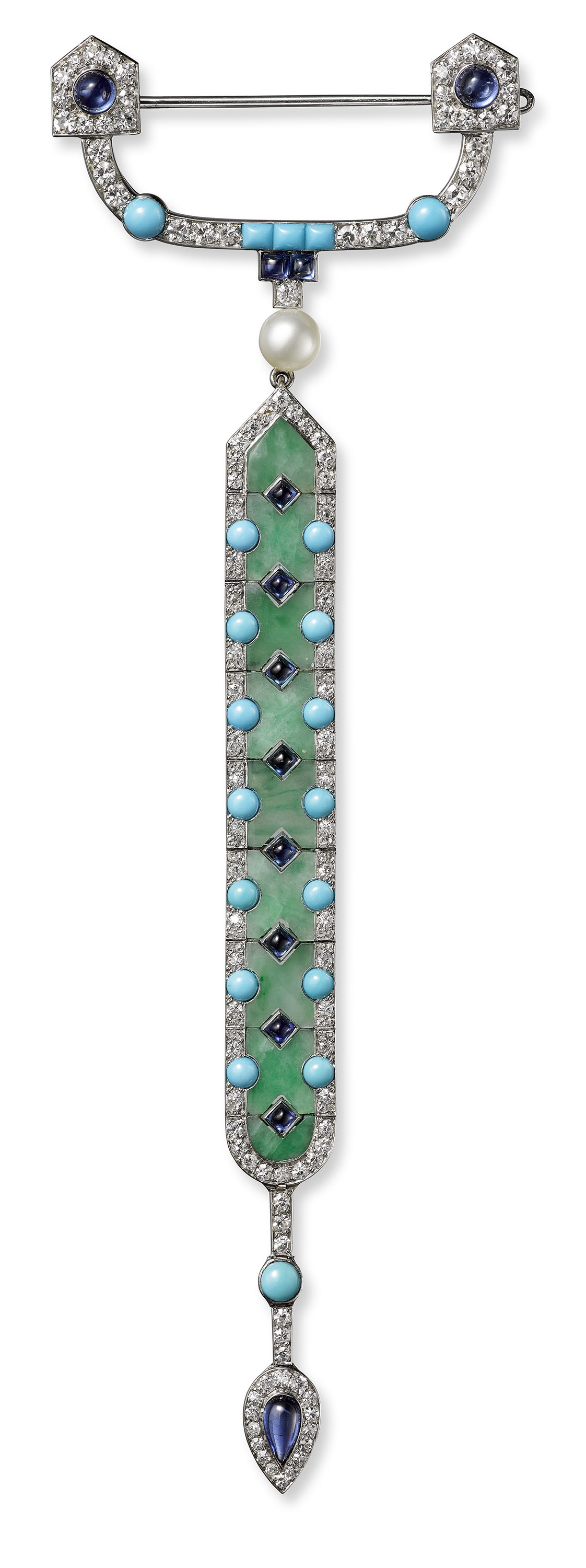

Like the above-mentioned items ordered by Barbara Hutton in the 1930s, Cartier’s many designs employing jade also testified to the play of colors that the Maison began exploring as early as the first decade of the twentieth century. Influenced by the Ballets Russes and their colorful costumes, Cartier proposed daring combinations of bold colors. Jade was among the Maison’s favorite materials, unhesitatingly combined with the blue of lapis lazuli, sapphires, or blue enamel, the red of rubies, the orangey-red of coral or indeed with the black-and-white of onyx and diamonds. A Persian-style pendant brooch of 1913 testifies to Cartier’s precocious use of jade in a green-and-blue combination even before it became popular during the Art Deco period. The pendant was composed of nine articulated plaques of jade rimmed with diamonds and alternately interspersed by lozenge-shaped sapphires or turquoise cabochons.

Apprêts

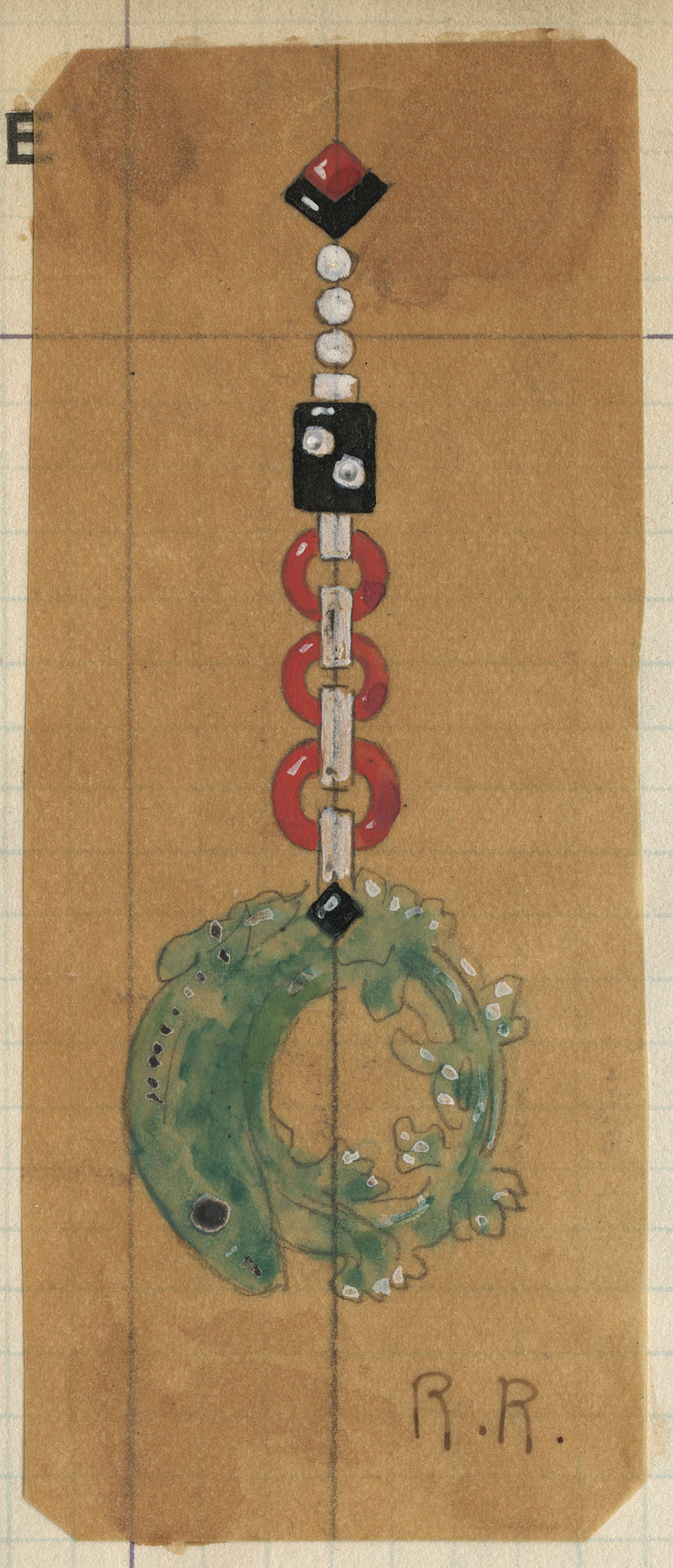

Most of the pieces of carved jade, whether large or small, fragmentary or not, came from Cartier’s stock of apprêts, or “trimmings,” which referred not only to several types of findings and components of jewelry, but also antique items purchased from dealers and gallery owners who specialized in the arts of Egypt, the Orient and the Far East (such as Mallon, Kalebjdian Frères and Vitali Fransès). These would then be incorporated into a Cartier design or sometimes sold to a client directly. Jade thus appeared in the form of batches of large or small plaques, belt buckles, bottles, hairpins, tiny animal figurines (such as Fo dogs), and traditional round coins with a square hole in the middle. These jade objects, typical of Chinese culture, inspired Cartier designers to come up with new ideas based on them. A Qing-period head ornament of white jade, decorated with floral patterns, was thus turned into a delicate letter opener, dotted with cabochon-cut rubies.

Two plaques of green jade carved with foliage and animals were edged with coral, black enamel and diamonds to serve as the two sides of a vanity case. The Cartier London workshop devised a belt from twenty-one disks of jade resembling traditional coins, filling the hole of each disk with a ruby—the belt was sold to Polish singer Ganna Walska. Sometimes the clients themselves would supply the antique feature, such as a belt buckle carved with two facing dragons, which Cartier transformed into a brooch. Finally, the dials of certain clocks were designed around what seems to have been a jade bracelet. Cartier continues to perpetuate this tradition, as witnessed by a box of pink gold with ebony finish, made from an ancient carved jade plaque, displayed at the Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris in 2010.

Mystery clocks

A special chapter in the story of Cartier’s use of jade is illustrated by mystery clocks. Between 1922 and 1931, the Maison devised a series of fourteen clocks decorated with animals or figurines: the dial was set on the animal’s back or on a base alongside the carved feature. The archives do not reveal the exact origin of these sculptures, but they are known to be of Chinese origin and to pre-date the twentieth century; some of them probably came from Cartier’s stock of apprêts.

Of those fourteen wondrous clocks, ones using a piece of jade sculpture are listed in the archives as “Mandarin Duck Clock” (1922) “Carp Clock” (1925), “Chinese Vase Clock” (1925), “Elephant Clock” (1928), “Lions Clock” (1929), and “Kuan Yin Clock” (1931). The Carp Clock, although not, strictly speaking, a mystery clock, is part of the group because two eighteenth-century gray-jade fish are set on an obsidian base-plate, swimming in mother-of-pearl “waves,” edged in blue enamel and dotted with cabochon rubies.

On the back of the larger carp is the fan-shaped clock dial. The movement of the Elephant Clock is hidden in a little pagoda on the animal’s body. Finally, the last in the series is the Kuan Yin (or Guanyin) Clock : the nineteenth-century jade sculpture shows the Buddhist deity Guanyin, spelled “Konan-in” in the ledger of apprêts. The fact that the figure holds a basket of fruit also associates it with a Taoist immortal character, Lan Caihe. A little Buddhist lion at the side holds a coral flower in its mouth. The clock dial is placed on a base of nephrite similar to the one used for the deity.

The technical feat of the mysterious movement was thus combined with precious materials and the ingenious re-use of ancient artifacts, turning Cartier’s mystery clocks into veritable marvels of clockmaking.

Creativity today

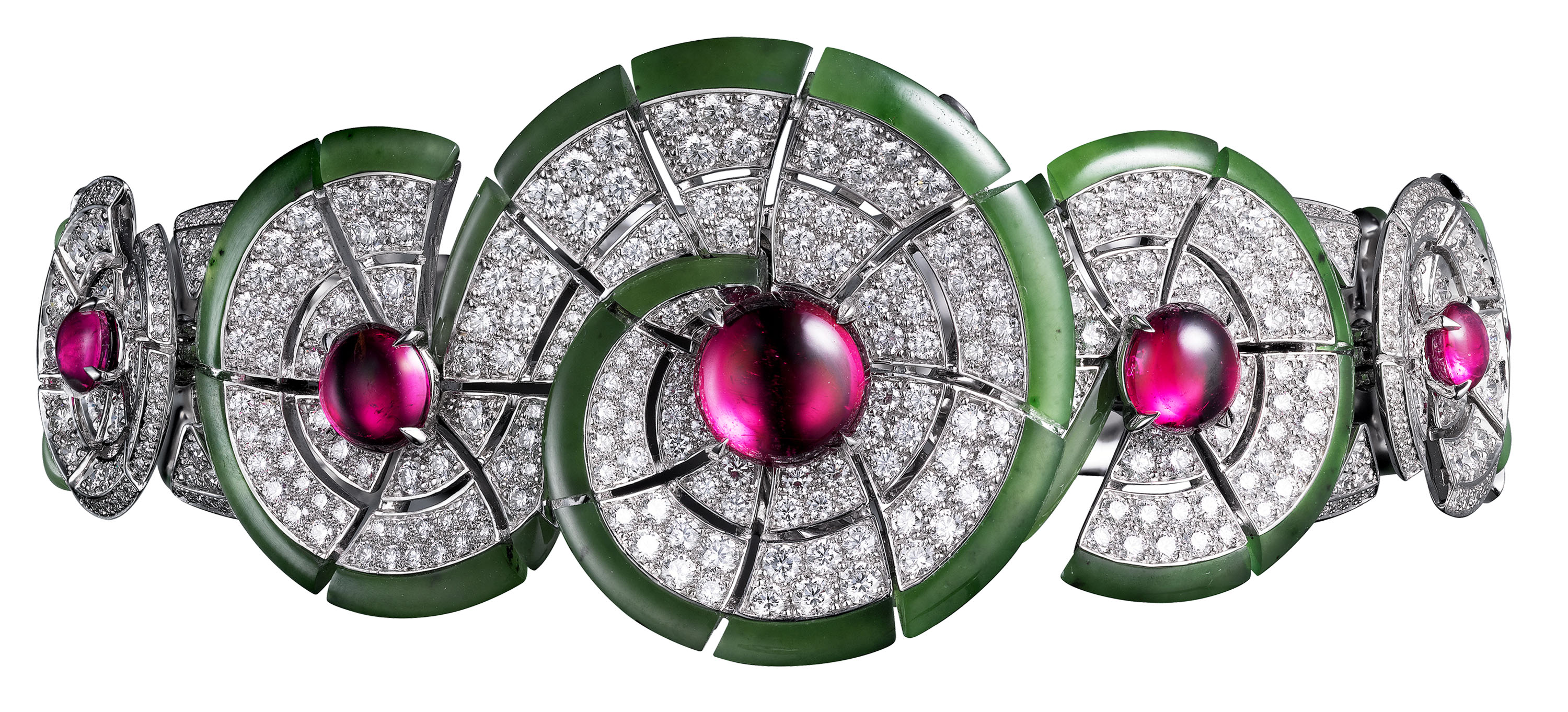

Cartier continues to explore bold color combinations today. A matching set of necklace, bracelet and pendant earrings depicts stylized lotus flowers in a nod to Asia as imagined by the jeweler. A cabochon rubellite marks the center of each flower, whose edges are indicated by green jade.

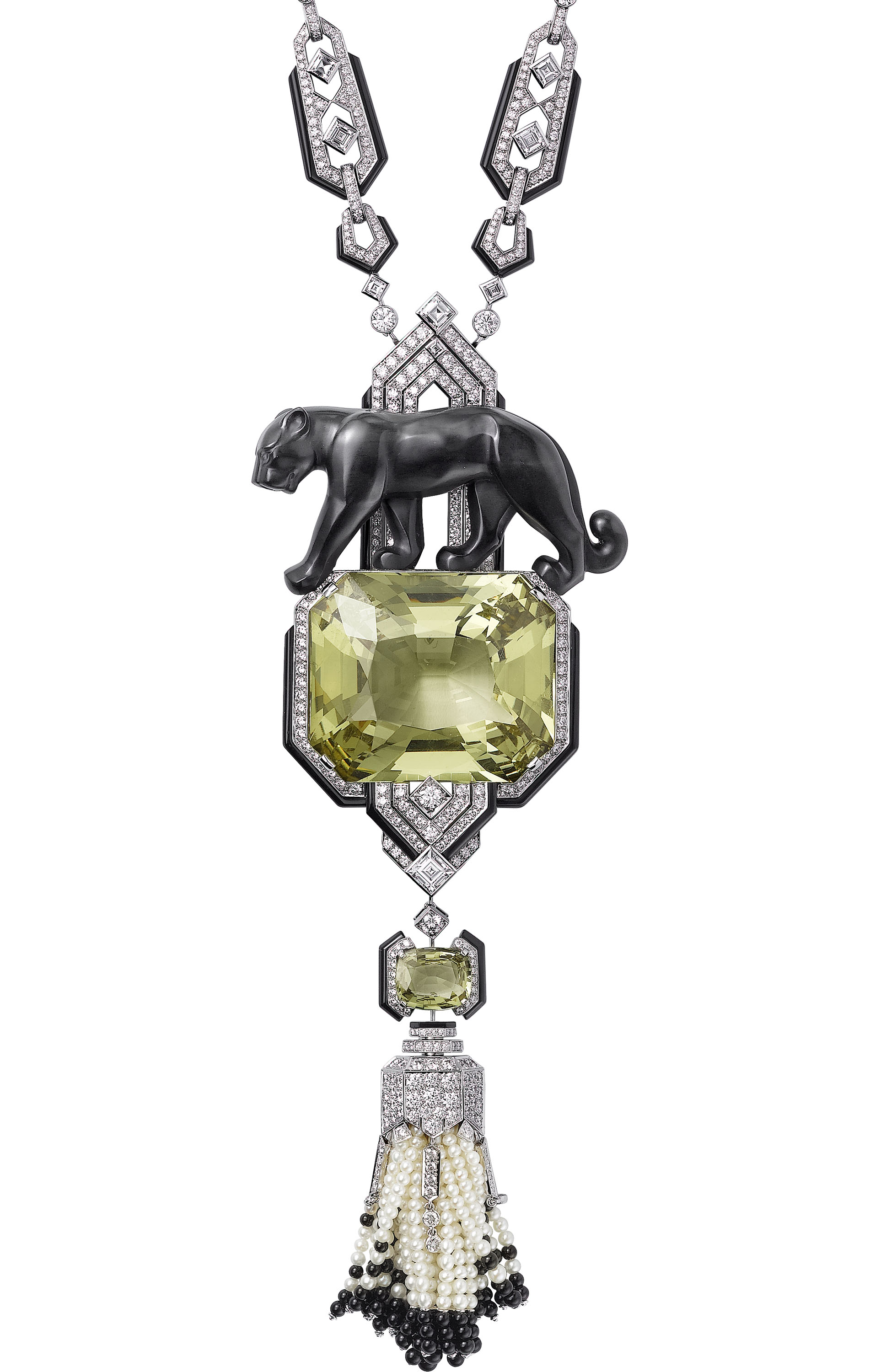

Contemporary jade designs come in many shades: sometimes black, or bluish-purple, or pale or dark green. This colorful approach is exemplified by rings featuring a panther which toys with a cabochon of multi-hued jade. A powerfully visual bracelet designed in 2014 plays on two shades of green—the pale green of chrysoprase and the stronger green of nephrite—in order to simulate the three-dimensional view of a veritable honeycomb structure.

Working in stone continues to be a real challenge for artisans. During the Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris in 2014, Cartier exhibited a necklace composed of a black jade panther carved by the Maison’s own workshop using ancient glyptics techniques. The big cat crowns a 121.81-carat yellow beryl.

Thus, ever since the late nineteenth century, Cartier has consistently employed jade for magnificent designs that pay tribute to the precious, age-old stone.