In the early twentieth century the Cartier brothers opened their designs to various non-Western influences, including the arts of the Islamic world. Mughal India, Persia, North Africa, and the Ottoman empire all subsequently fueled the Cartier imagination.

Right from the dawn of the twentieth century, the Cartier brothers showed an interest in the Orient. Louis not only visited museums and galleries on a regular basis, but was also a pioneering collector in this sphere. He is known to have attended a key exhibition of “Muslim arts” organized in Paris in 1903 by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. In 1912 he lent several items of his collection to the first retrospective of Persian miniatures to be held in Paris. Far from a Romantic taste for mere exoticism, Louis was seeking an inexhaustible new source of motifs and ideas that would help to forge the Maison’s stylistic identity.

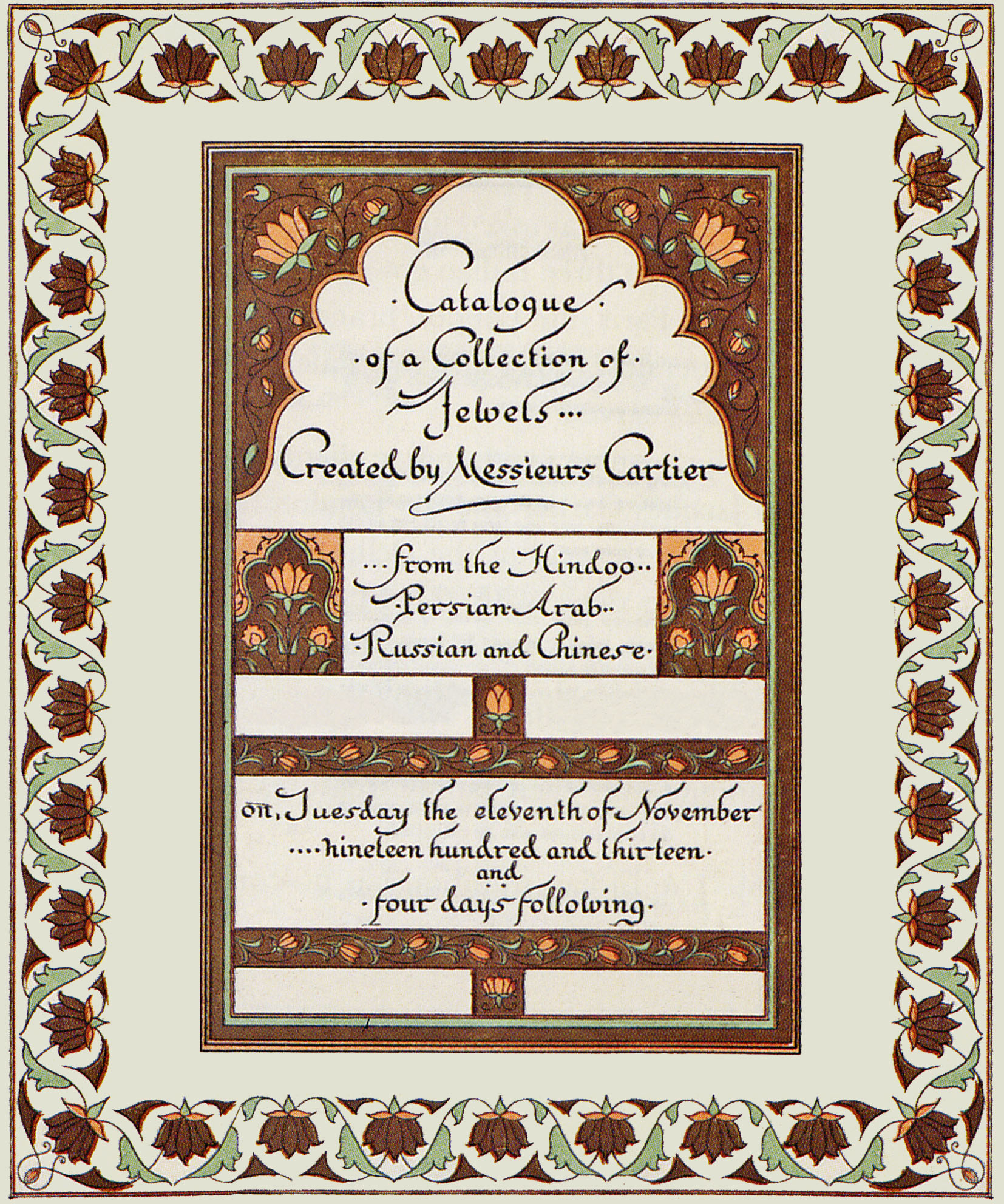

In November 1913, Louis, Pierre, and Jacques Cartier held an exhibition of A Collection of Jewels Created by Messieurs Cartier from the Hindoo, Persian, Arab, Russian, and Chinese in their Fifth Avenue showroom in New York, following an earlier presentation in their Paris premises.

While this title reflects unabashed eclecticism, a look at the designs reveals a subtle, profound knowledge of the artworks from which they drew inspiration.

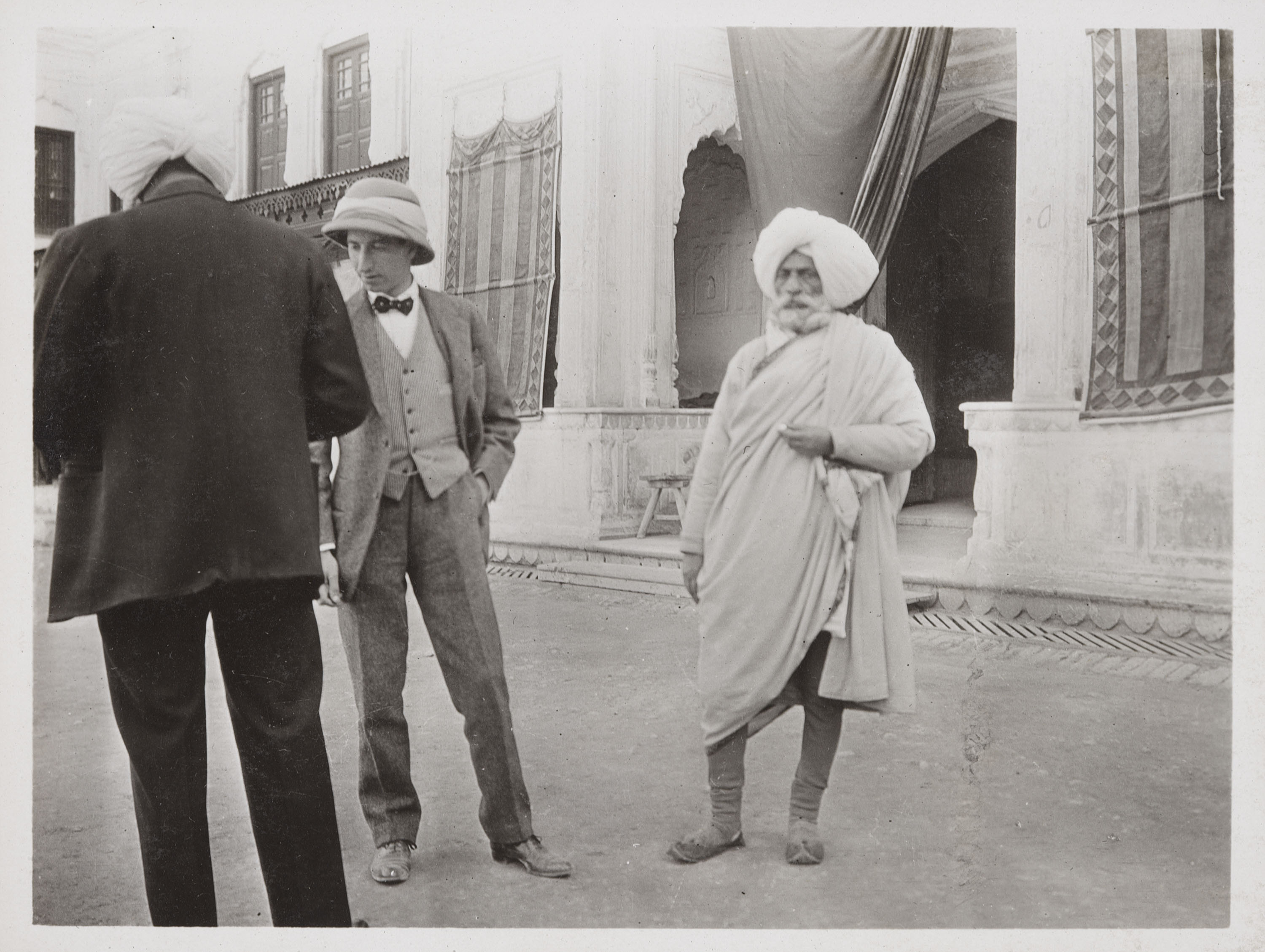

Jacques made several trips to the East in order to develop his knowledge of the terrain. As early as 1911 he visited the Persian Gulf and India, in time for the proclamation of George V as emperor of India. He met dealers in pearls and gemstones, visited glyptics workshops, watched traditional artisans at work, and encountered potential clients.

The Cartier archives refer to the still-vague categories used by early studies on Islamic arts, such as “Persian decoration” or “Arabic decoration,” failing to convey the variety of inspiration that a modern eye can detect in these historic Cartier pieces. While Persia and Mughal India were obvious sources, North Africa, Ottoman Turkey, and the Levant also influenced many Cartier designs.

The Mughal empire

Cartier maintained close ties to India, notably through its London branch, which Jacques Cartier headed from 1909 onward. Like his brothers, Jacques drew inspiration from both the Hindu and Muslim cultures there.

Based on jewels made in India (some of which were imported and sold by Cartier without alteration), house designers invented long necklaces composed of ruby, emerald, and sapphire beads. Those large Indian stones, sometimes baroque in cut or pierced to allow for a silk thread, were surprising to the eye of Western clients accustomed to smaller, faceted gems. Similarly, the profusion of stones and their color combinations launched a fashion far removed from jewelry of the time, one that enjoyed its heyday from the late 1920s to the late 1930s.

Yet Cartier’s great originality lay in the re-use of old gems in modern designs, notably large Mughal emeralds carved with floral motifs or lines of poetry, dedications, and quotations from the Koran. The purchasers of such pieces were both Western celebrities (Marjorie Merriweather Post) and Indian princes (the maharajah of Patiala). One item illustrating this trend is a pendant (later converted into a shoulder brooch) made by Cartier London in 1923, employing several emeralds probably engraved in India in the nineteenth century. One of the stones is inscribed with the name of a Persian monarch, Shah Abbas, which makes the jewel an extraordinary piece for both a specialist in Western jewelry and an historian of Islamic art.

Little enameled plaques decorated with birds and flowering branches, made in the Jaipur region in the nineteenth century, were another inspiration from traditional Mughal art. The plaques were set on Cartier cigarette and vanity cases, which they enlivened with hues of red, green, and white.

The Tutti Frutti style derived from these new trends, rapidly became a key element of Cartier style from the mid-1920s onward. Rubies, emeralds, and sapphires, were cut and carved in the shape of leaves and then assembled in branches that might be dotted with berries and fruit of precious stones. Here Cartier created a new style, grounded in its own day, although inspired by Mughal jewelry in the choice of gems, the cutting and carving of those gems, and the combination of the colors red, blue, and green. This interest in unconventional combinations of hues (blue and green or blue, green, and red) may also have been piqued by the Ottoman pottery that was highly fashionable among European collectors in the early twentieth century.

Persia

The revival of color that characterized Cartier designs as early as 1903 was reinforced by the establishment of Sergey Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris in 1909. The dance troupe triumphed there for the next decade. Its designer of sets and costumes, Leon Bakst, created an aesthetic shock that rocked the worlds of art and fashion. The lavish, intensely colorful atmosphere of the ballet Scheherazade notably struck imaginations of the day, reviving a “Persian” style. To accompany the evening gowns worn by elegant ladies, Cartier devised aigrettes directly inspired by male headdresses worn in the Islamic world.

The Maison also enriched its chromatic palette by employing semi-precious stones often found in Oriental jewelry—turquoise, jade, lapis lazuli, and coral—in bold and unusual combinations.

Beyond this mode for exotic touches, Cartier designers worked on detailed ornamentation that revealed their profound appreciation of Islamic art. Some motifs, such as arabesques, “entwined Ts,” and multifoiled cartouches could be found on brooches, cigarette cases, and vanity cases with decoration directly inspired by inlaid metalwork from Iran.

Finally, representational motifs common in Persian art, such as paisley leaf, cypress tree, and flying phoenix were borrowed as such. Louis Cartier would even go so far as to insert a fragment of a Persian miniature on a cigarette case of nephrite.

Other horizons

The art of Ottoman Turkey, although more discreet in Cartier designs (because subsumed under the label of “Persian art”), is equally apparent on certain items, such as a turquoise and pearl vanity case made in 1924, whose composition evokes an Ottoman binding. Then there was a 1932 enameled gold cigarette case featuring rabbits and gazelles against a scrolling ground very similar to the spiraling pottery made in Iznik in the 1530s and 1540s. A vanity case of 1936 that once belonged to Daisy Fellowes was decorated with a jade plaque adorned with stones in elaborate collet settings typical of Ottoman art. Diamond chokers dating from 1907 to 1909 employed wavy patterns that evoke the silks and velvets worn by the lords of Istanbul.

The influence of “Arabic” art on Cartier jewelry is simultaneously more discreet and more profound than that of India and Persia. One of the main movers behind this trend was Charles Jacqueau, a Cartier designer from 1911 to 1935. The many surviving sketches by his hand reveal his attraction to the geometric, abstract decoration found in North Africa.

It was above all the spirit of this artistic tradition that would imbue the new style devised by Cartier in the early years of the twentieth century. Simplified shapes, a pronounced bent for geometry and stylization, and the abandonment of representational decoration in favor of bold abstraction: this style, dubbed “modern,” would break with the conventions of jewelry at that time and was all the more surprising for being contemporary with the garland style then associated with Cartier. As early as 1904—keeping in mind that Louis Cartier went to the Muslim arts exhibition in Paris in 1903—a little brooch with straight lines and acute angles prefigured the aesthetic revolution that would lead to the Art Deco of the 1920s. As a pioneer, Cartier began making tiaras, headbands, brooches, and bracelets whose elegant sobriety was perfectly in keeping with the new ladies’ fashions of the 1910s, based on straight lines and loose fabrics.

Today

Still today, many Cartier designs reflect an artistry sensitive to Islamic crafts, such as bracelets with polygonal stars whose rigorous web of lines is softened by subtly shaded semi-precious stones, and cabochon rings imitating the shape of archer’s rings worn by Mughal princes. This gaze toward distant horizons continues to inspire Cartier designers.