Depending on when it is made, sold and worn, jewelry may carry political connotations that convey a demand, a warning or a commemoration. A personal item of jewelry thereby becomes a living record of history. Cartier’s history includes two world wars that changed society and mentalities forever.

The First World War

On June 28, 1914, a Serbian nationalist’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, changed the course of history by plunging the world into a war with tragic consequences. Those four years of war were obviously not conducive to the making of lavish jewelry. The pace of work slowed in the Cartier workshops, where most employees were drafted into the military, including the three Cartier brothers, Louis (1875–1942), Pierre (1878–1964), and Jacques (1884–1941). Echoing the tragedy rocking Europe, the tone in the workshops became more serious.

This context gave rise to designs that diverged from traditional jewelry. Items such as brooches and charms often adopted a representational form and played on patriotic themes. Charms were usually modest in size and featured only smaller stones. They might soberly display the colors of the French flag, in the form of a red, white and blue cockade, or else reflect a military theme: there were airplane, machine-gun, bayonet, and even Red Cross charms. The Belgian king himself bought similar items with the colors of his nation’s flag. Designs that previously had no martial connotation were also reinterpreted—little bow brooches were retooled as “propeller” brooches and became highly popular when they were sold during the war years.

Then came the joyful period of victory, when Cartier jewelry celebrated French pride. The Arc de Triomphe was often featured, and colorful stones returned to the fore. In 1919, a brooch with that motif was made of gold, platinum, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, topazes and sapphires. Sapphire cabochons symbolized the helmets of the soldiers in the grand victory parade down the Champs-Élysées on July 14, 1919.

It was not just the French clientele who appreciated this kind of jewelry. The maharajah of Patiala, who fought on French soil under the British flag, bought a banner brooch made in 1919. This period also gave birth to the first items alluding to Franco-American friendship, symbolized, for example, by a brooch that combined the two flags and by a pin that mimicked “Uncle Sam’s” hat.

The war left its scars. Jacques Cartier was gassed in battle and thereafter had frail health, as did designer Charles Jacqueau, who was granted the special status of being allowed to work at home while undergoing treatment.

The Second World War

The war that broke out in Europe in 1939 had serious organizational and structural consequences for the family-run Cartier. This was notably true of the Paris branch, which continued to function during the four years of German occupation. Although the Paris boutique temporarily shut in June 1940, the German occupiers ordered it to reopen just a few weeks later. The company headquarters, however, was reorganized in Biarritz, in the unoccupied zone of France. That is where two Cartier brothers, Louis and Jacques, sought refuge in the hope of reaching the United States, given their frail health. Neither one, unfortunately, lived to enjoy the happy days of liberation. Each died far from their Paris home—Jacques in Dax, southern France, in 1941, and Louis in New York in 1942.

The staff that remained in Paris, including Jeanne Toussaint, reorganized as best it could. Many artisans and salesmen were drafted; the pace slowed in the workshops; most stock was sent to the unoccupied zone. And yet this period remains interesting from the standpoint of jewelry designs that explored patriotic feeling in an extremely complex situation.

Indeed, rebellion against the occupying army could not be expressed openly, as it had been in the early months of the war—an example of which were brooches with the French rooster wearing an army helmet, made in the workshops just a few weeks before German troops arrived. By June 1940, patriotic jewelry had to be more discreet. Apparently cheerful designs were made to carry messages more political than they seemed.

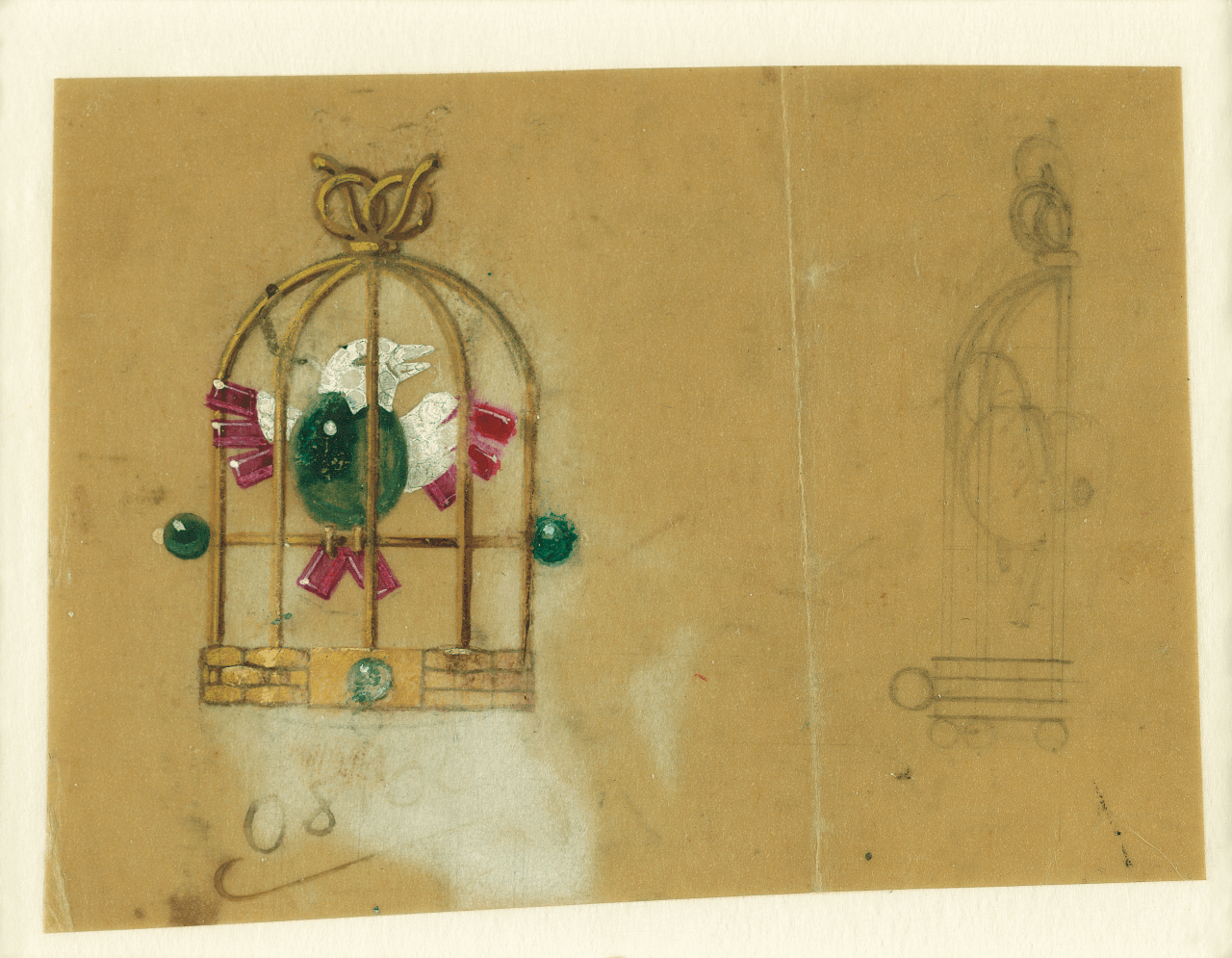

One emblematic item of Cartier jewelry during the war was the Oiseau en cage (caged bird) brooch made in 1942 at Toussaint’s initiative, to a design by Peter Lemarchand. These little brooches were symbolically placed in the display window of the Paris premises. Although seemingly naïve—some cages were topped by little bows, for instance—the image of the caged bird in fact embodied a lively protest against the occupiers. When the Liberation came, newer designs delivered a message of hope, such as bird brooches made in November 1944 with the slogan “1945 Will Be Better” and other flower brooches in patriotic colors, suggesting that sunnier times were on their way.

Across the Channel, the London branch mobilized to support the war effort. In the absence of Jacques Cartier, it was headed by the sales manager, Étienne Bellenger. Bellenger entered into a contract with the British government to convert part of the company workshops in order to make precision parts for the aeronautic industry. In addition to a desire to help the war effort, this decision limited the number of jewelers who were drafted, thereby saving the loss of highly qualified staff.

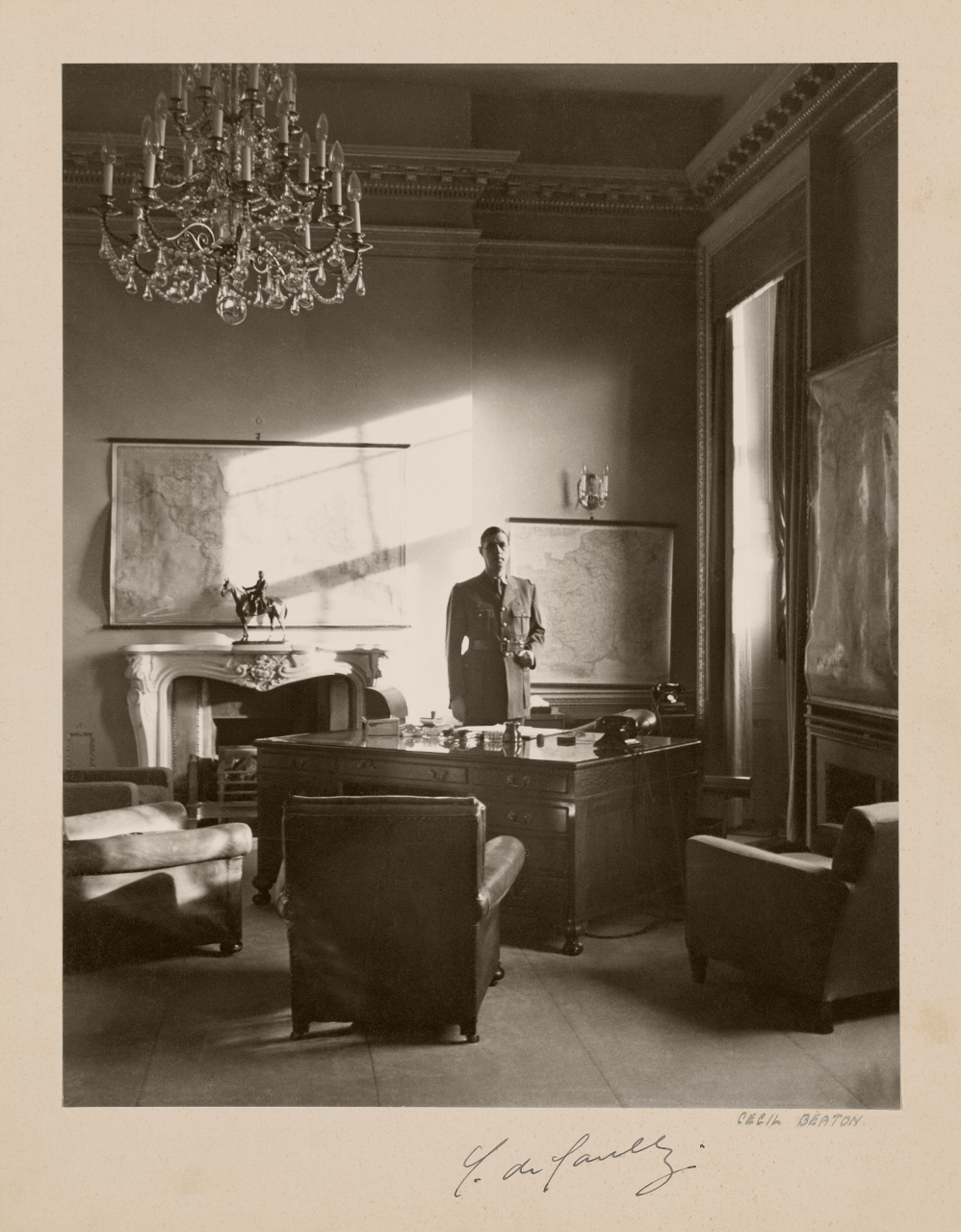

When Charles de Gaulle arrived in England in June 1940, he was welcomed by Bellenger himself, who housed the general’s family in his own home in Putney, southwest London. The general, who was not yet very well known, came to England with one clear goal—to take the helm of the Free French Forces in Britain. Bellenger acted as an intermediary, organizing dinners and private meetings, thereby introducing De Gaulle to influential people who could help him attain that goal.

Brooches and pendants designed by George Charity to feature the Cross of Lorraine (symbol of the Free French Forces) soon became popular in London. Like the ones ordered by Lady Ashley, most were set with rubies, sapphires and diamonds. Entirely gold versions were also made in Paris in the weeks following the Liberation. De Gaulle himself bought ten identical ones in 1945.

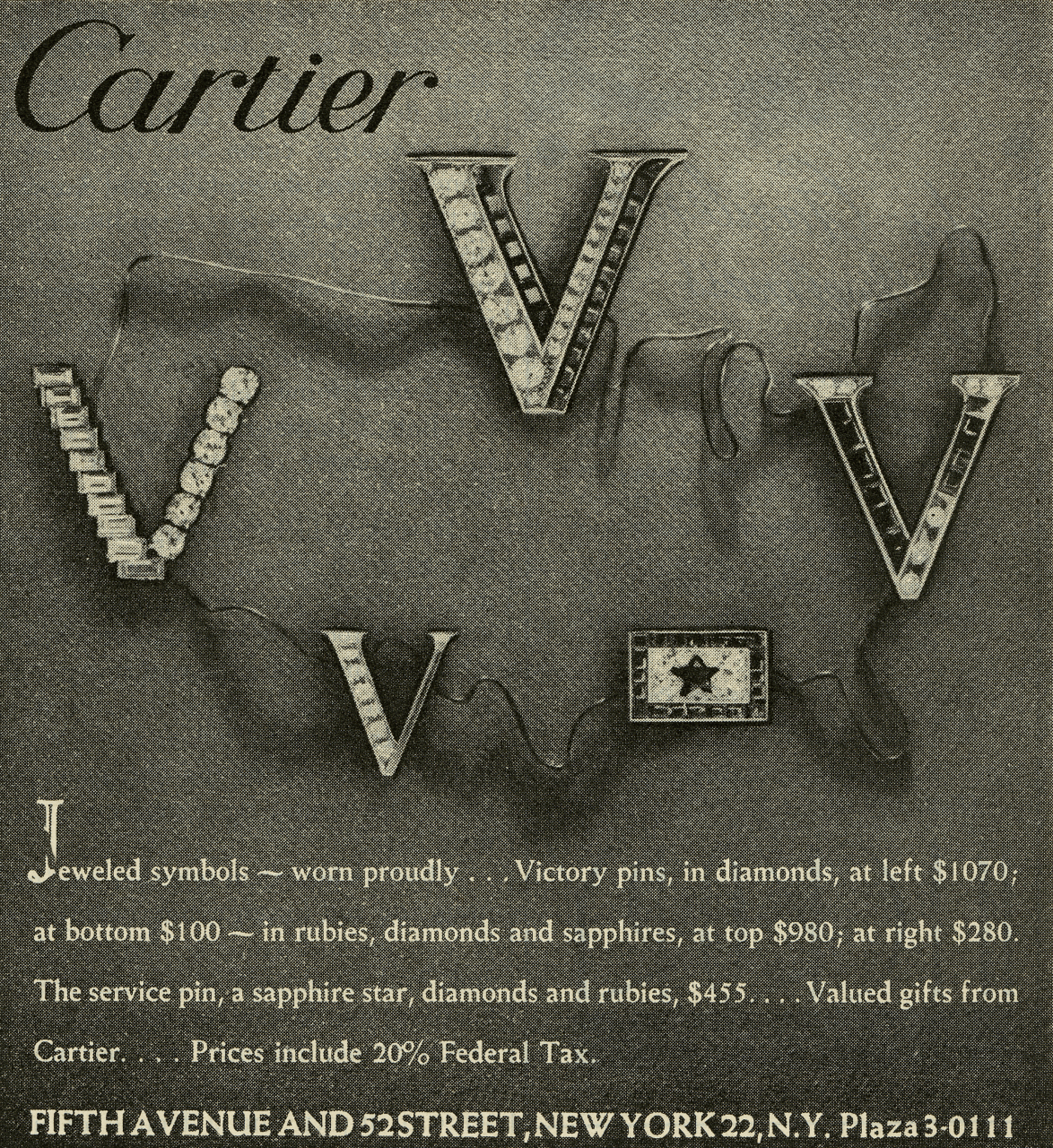

In America, little brooches bearing the V for victory became popular. Pierre Cartier was in regular contact with Bellenger, and provided financial support for the cause, as witnessed by a telegram now in the Cartier London archives. Dated July 29, 1940, the cable documents Bellenger’s request to Cartier for funds to aid roughly two hundred French soldiers who had arrived in England, as well as to pay for surgical equipment.

Meanwhile, Pierre and his wife Elma fulfilled various official functions, even appearing at the White House. In fact, Pierre usually sent a Christmas present to Franklin Delano Roosevelt every year. In December 1943 he gave the American president a desk clock that told the time in five different time zones. It’s base was inscribed with a dedication in French that could be translated as: “The hour of worldwide victory. In tribute to its architect, the president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

The hour of victory was indeed near. It would be celebrated by emblematic Cartier pieces such as the Oiseau libéré (free bird) brooch. The little bird that symbolized the years of occupation could finally leave its cage and fly.

A client who symbolized the Resistance

While Cartier’s design decisions during the war years fully reflect the jeweler’s ability to move with the times, occasionally it is the less well-known items that provide the most moving testimony.

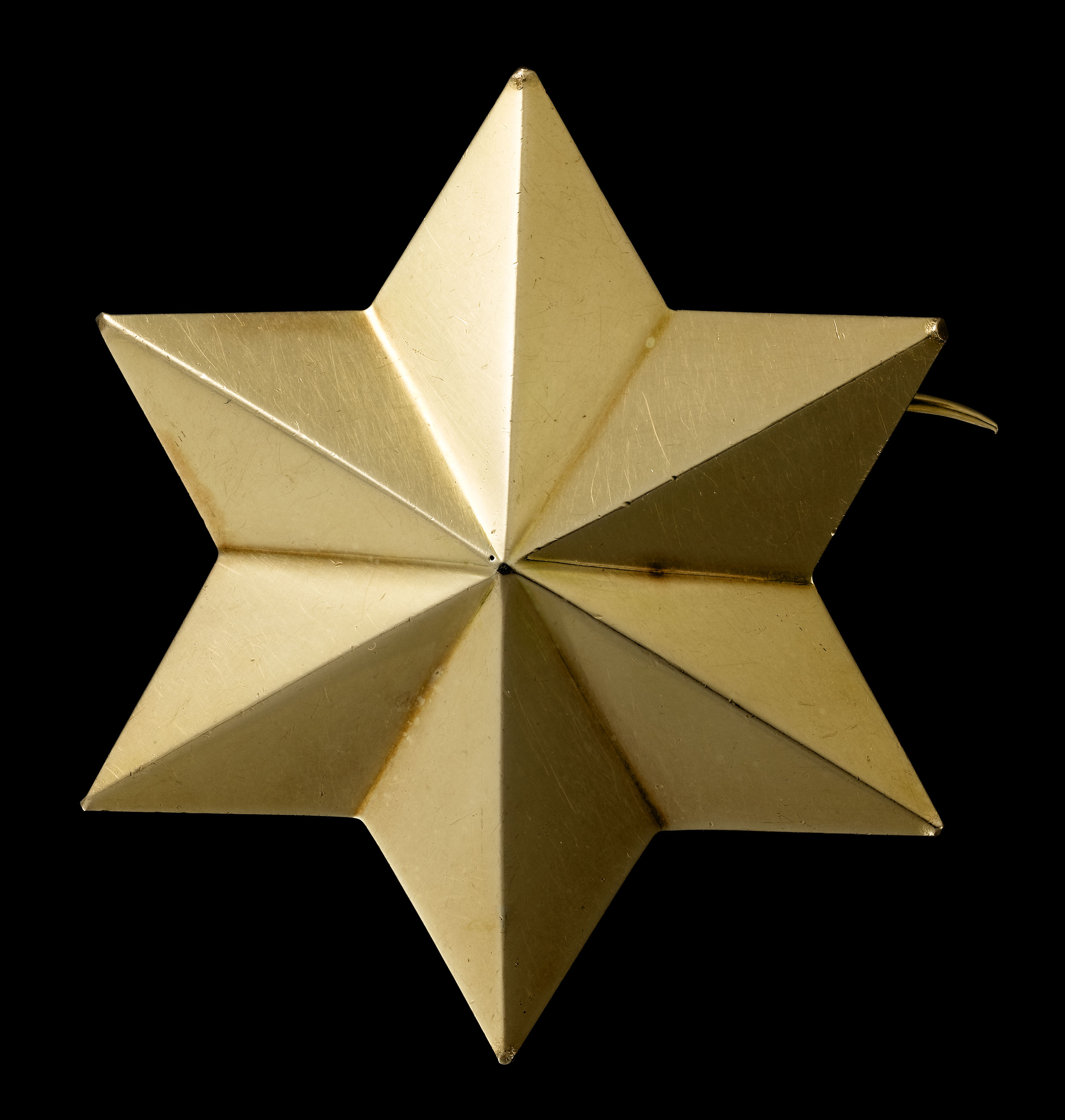

Thanks to the heirs of one client, Cartier recently learned the full story behind a gold star ordered in 1942 by Madame Françoise Leclercq (1908–1983). Coming from an affluent, traditionally Catholic family, Leclercq joined the Resistance in 1941. Many clandestine meetings were held in her home on Rue Montpensier in Paris, where she also housed people sought by the Gestapo.

Horrified at the round-up of thousands of Jews in Paris and its suburbs, and at the decree that all Jews in France must wear the yellow star, Leclercq went to the Cartier boutique in September 1942 carrying her baptismal and first-communion medals, which she had Cartier melt down in order to make a star. She wore this yellow star publicly in the streets of occupied Paris.

Alongside her numerous actions with other members of the Resistance, Leclercq’s decision to order this yellow star was a personal initiative: as a gesture of solidarity with persecuted Jews, wearing this item of jewelry was a highly moving, very personal act of resistance.