The emerald is a green variety of beryl. It is one of the four recognized precious stones, along with the sapphire, the ruby and the diamond.

- Group: beryl

- Chemical composition: beryllium aluminum silicate

- Color: from light green to dark green

- Hardness: 7.5 (Mohs scale)

- Sought after origins: Colombia, Zambia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Brazil

Etymology, myths and legends

The word emerald in English, émeraude in French, smaradg in German and many other similar names derive from the Latin smaragdus, itself borrowed from Greek.

The emerald’s appeal is due to its beauty and rarity – embodying the wealth and power of its owner – but also to the virtues attributed to it. It symbolized life and immortality for the pharaohs, fertility for women in Antiquity, and it is also the emblematic color of Islam.

The emerald has given birth to many legends. One of the most astounding examples recounts that the cup of the Holy Grail, used to catch Christ’s blood, was cut from a single emerald. Some authors say that the gem adorned Lucifer’s forehead and fell from it during his battle with the Archangel Michael. In addition to the therapeutic powers attributed to the emerald in ancient times, the stone is also believed to offer protection. In Mughal India, holy verses were carved on emeralds then worn as talismans. Native Americans believed that emeralds could heal the body, heart and soul.

In his encyclopedic work entitled Natural History, Pliny the Elder (23-79) wrote about the emerald: “Indeed there is no stone, the color of which is more delightful to the eye ... no green in existence of a more intense color ... this is the only one that feeds the sight without satiating it.” He also highlighted their soft brilliancy and unchanging colour, regardless of the intensity of the light.

Cleopatra liked to wear jewels, especially when set with emeralds, for which she is said to have had a deep passion. The mines bearing her name, which were once believed to be only mythical, were rediscovered in the nineteenth century. They are located near Sikait, between the city of Luxor on the Nile and the Red Sea, and were probably explored between 3000 and 1500 BCE. Emeralds simply cut from the rough and pierced with a hole in their center were worn on necklaces during that time.

Pliny wrote that Nero used an emerald to watch circus games, which has given rise to many different interpretations and controversies.

Formation of the stone

The emerald belongs to the beryl family, of which it is the most precious variety. Its green hue results from the replacement of aluminum atoms in the mineral’s structure by chromium and vanadium. Geologically speaking, these elements are theoretically incompatible, so their encounter can only be accidental and therefore rare.

Beryl crystallizes in the form of elongated hexagonal prisms that are smooth or streaked.

The colour of the emerald is a balance of blue and yellow, which mix to produce a green of varying intensity, ranging from very light to very dark. The emerald’s dichroism accentuates either the blue or the yellow tint, depending on the angle from which the stone is observed. Colour is not always evenly distributed, and some parts of the gems could be less or more colored.

Origins

A gemstone’s origin is not a guarantee of quality, although it is a recognized criterion in determining its value. Colour indications according to origin are based on assessments made by professionals and observations pertaining to a majority of high-quality stones from that provenance. It is customary to indicate the country of origin on gemological certificates. The mine location is rarely specified.

The earliest known mines were explored in ancient Egypt by the pharaohs, and then in the Habach Valley in Austria by Celts and Romans, but the unearthed gems seem to be few and of mediocre quality.

It was at the end of the fifteenth century that the abundant deposits of Colombia, which the indigenous Indians attempted to keep secret, were rediscovered and mined by the conquistadors. They supplied large quantities of gem-quality emeralds to European courts and filled the treasure chambers of the Middle East and Asia, probably via the Silk Road. It was on Mughal jewelry, and later that of the maharajas, that emeralds were the most abundant. In the early twentieth century, fascinated by Cartier’s modernity, Indian sovereigns would bring a considerable number of these gems to the bold and visionary jeweler.

Many other deposits were discovered in the modern era, notably in Russia (the Ural Mountains) in 1830 and in Africa. Those in western Asia—Tajikistan, Pakistan and Afghanistan—may be no more than rediscovered mines already worked in Antiquity.

The quality of emeralds from the age-old deposits in Egypt and Austria and the more recent sources in the Ural, India, Australia and Nigeria is not high enough for selection by Cartier.

These days, the largest emerald deposits are located in Colombia, Brazil, Zambia and, more recently, Ethiopia. Smaller deposits also exist in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

South American mines

Colombian emeralds

The main Colombian production sites are the historical mines of Chivor and Muzo and, more recently, Cozcuez and La Pita. The best-known, the Muzo emerald, boasts a deep, luminous green, while a Chivor specimen is lighter and bluish, often with very few inclusions. , According to a 2011 survey, Colombia produces 55% of the world’s emeralds.

The formation of Colombian emeralds is unique and not found anywhere else in the world. The crystals grow to significant sizes, sometimes resulting in cut stones weighing more than 100 carats.

The three-phase inclusions seen in Colombian emeralds, for many years believed to indicate origin, are jagged-edged fluid inclusions of an infinite variety containing gas, salt crystal and solid crystal. They continue to be typical of Colombian stones. Solid inclusions, such as calcite or pyrite crystals, partially or fully healed fractures (recrystallizations of fractures during the formation of the stone), two-phase inclusions, and parallel growth zones can also be found.

Brazilian emeralds

Of significantly older formation and geologically different from Colombian stones, Brazil’s emeralds only supply gem-quality crystals of a relatively small size. They are mainly used at Cartier for pavé settings or for eyes in animal designs, and much more rarely as central stones, mostly oval-shaped. They are characterized by a very large variety of two-phase crystals and inclusions as pyrite, mica, growth tubes, colour zoning, and open or healed fissures.

Asian mines

Pakistan and Afghanistan provide very high-quality gems but in relatively small quantities.

Emeralds from Pakistan

In Pakistan, the Swat Valley mines located in the north of the country are known to produce emeralds of high quality, of an intense, luminous green with very few inclusions. The stones are geologically very close to Colombian gems and display the same types of inclusions. A cut stone weighing more than 2 carats is a rare find.

Emeralds from Afghanistan

Afghan emeralds have been mined in the Panjshir Valley since 1970. Studies are underway to determine if these are the same mines that were described in Antiquity in this part of the world. The formation of Afghan gems is similar to that of Colombian emeralds. Multi-phase fluid inclusions containing a series of salt crystals, gas and solids are, along with pyrite crystals and other minerals and the presence of growth zoning, indications of Afghan origin. Whether faceted or polished, the best specimens of Panjshir emeralds can reach weights of 20 carats, with outstanding color and exceptionally well-formed crystals.

African mines

The African continent is home to significant emerald deposits, often quite recently discovered and mainly located along the Indian Ocean coast. Ethiopia, Zambia and Zimbabwe are among the largest producing countries.

Emeralds from Zambia

The production of Zambian emeralds near the Congo border has been increasing since the deposits began to be mined in 1969. Their green colour often has a bluish tint and ranges from light to dark. The jewelry-quality emeralds rarely weigh more than 6 carats; they can be cut in round or oval shapes as well as step-cut, faceted or cabochon. Tourmaline and spinel crystals, among many other substances, may be present in Zambian emeralds.

Emeralds from Ethiopia

Pliny sang the praises of Ethiopian emeralds in ancient times, before these mining regions fell into oblivion.

New gem-bearing areas in Ethiopia began to be probed in 2012 and are reported to offer a great deal of potential.

Emeralds from Zimbabwe

Called Sandawana emeralds after the name of the mine, emeralds from the country formerly known as Rhodesia have provided small but very beautiful gems with vivid, saturated color. These mines are reportedly depleted.

Oiling of emeralds

Emerald oiling, a lapidary process already recorded in ancient times, has been practiced ever since. It involves allowing a liquid, traditionally a colorless oil, to penetrate the stone and make an optical connection between the two walls of any fractures that were initially empty or filled with water vapor or air. Because the refractive index of these substances is different from that of emerald, light is reflected in a sub-optimal manner. The refractive index of oil being more similar to that of the emerald, this phenomenon is mitigated.

Through various analyses, laboratories determine how inclusions have been filled by quantifying the filler and identifying its nature if possible. The most common classification categorizes the “presence of a colorless substance in fractures” as “insignificant,” “minor,” “moderate,” or, something that is extremely rare at Cartier, “significant.” A very small number of emeralds reveal no filler and can be categorized as “none observed.” In the latter case, some laboratories distinguish between emeralds with no surface fissures (rare) and those that have fissures that could be filled at a later time.

Every detail of these descriptions should be carefully examined when the stones are not being supplied by Cartier, and experts should be consulted to ensure proper understanding.

Oiling is a reversible procedure that does not harm or modify the stone. To date, Cartier does not accept any fillers other than oil.

It is recommended that emeralds be cleaned and re-oiled after a few years.

Emerald “garden” (jardin)

Solid or liquid inclusions and open or healed fissures characterize the majority of emeralds. Different types of fractures in the gem reflect the complex formation of the stone. Inclusions and fractures intersect in the emerald, in relatively random proportions and no specific patterns. The descriptive term jardin, which is French for garden, uses imagery to describe all of the emerald’s visible inclusions. Rather than detract from the stone’s beauty, they add vibrancy and character.

“Gota de aceite” emeralds

Some Colombian emeralds are described as “gota de aceite” (drop of oil). This is because of the syrupy crystallization that can be seen under magnification, giving the stone a characteristic velvety appearance and significantly heightening its appeal.

“Old mine” emeralds

Much debate surrounds the use of the term “old mine” in the gemstone community. Does it describe emeralds from medieval treasure chambers and the magnificent emerald collections of India, Persia or Turkey? In that case, it could also refer to emeralds from Asia and perhaps Panjshir and Pakistan, since their existence has been attested prior to the discovery of Colombian emeralds.

It is therefore customary in the gem trade to describe gems with very fine crystallization, usually relatively flat and with a warm, vibrant colour, as “old mine.” This is the subjective qualification of a professional and has no scientific basis. The term should not appear on a certificate and should be used sparingly.

“Trapiche” emeralds

A gemological curiosity of exclusively Colombian origin, the “trapiche” emerald somewhat resembles a wheel with a hexagon core and six trapezoidal spokes separated by black composite areas. Hexagonal or cabochon crystals are cut to enhance this star-like effect in the stone.

Cuts and shapes

The emerald cut, which is a step-cut rectangle or square, is the most common cut for central faceted emeralds. This cut is determined by the hexagonal shape of the rough stone. Depending on the direction of the cut, the blue or yellow tint will be emphasized.

Although less frequently, emeralds are also shaped into ovals and other forms used in jewelry: round (for small stones), pear or drop, facetted, cabochon, and briolette. The emerald is especially suited for carving, to create intaglio or cameo designs as well as Mughal flower motifs. Sculpted into leaves or beads, it is a key ingredient of Tutti Frutti.

Care recommendations

Emeralds must be handled with care to avoid scratches or chips.

Neither rhodium not ultrasonic treatments are safe for emeralds.

It is recommended to bring the emerald jewelry to a Cartier boutique for regular cleaning to avoid improper handling.

As previously indicated, emeralds should be cleaned and re-oiled on a regular basis after a few years.

Cartier and emeralds

The emerald occupies a special chapter in the history of Cartier.

It begins in India in 1911. During a trip to this country, Jacques Cartier discovered extraordinary emeralds carved with floral motifs or inscriptions of verses from poems or the Koran, according to a tradition dating back to the seventeenth century. Steeped in history and covered with a veil of mystery, they originally adorned ceremonial jewelry worn by Mughal sovereigns and were believed to have talismanic powers. Although the carved emeralds were first mounted singly in jewelry, Cartier quickly mingled them with other gems: starting in the 1920s, for example, it combined them with sapphires and rubies sculpted into leaves to create fresh new jewelry compositions which would later be called Tutti Frutti.

In addition to using contemporary engraved stones, Cartier is known for its revisiting of antique gems, such as the Bérénice emerald. Weighing 141.13 carats and featuring a natural hexagonal shape, it was probably carved in India in the seventeenth century. After being the central stone of a trio mounted in a shoulder ornament in 1925, it was removed from the setting the following year to be mounted first in one brooch and then a second brooch in 1927, before reappearing in Cartier's history decades later.

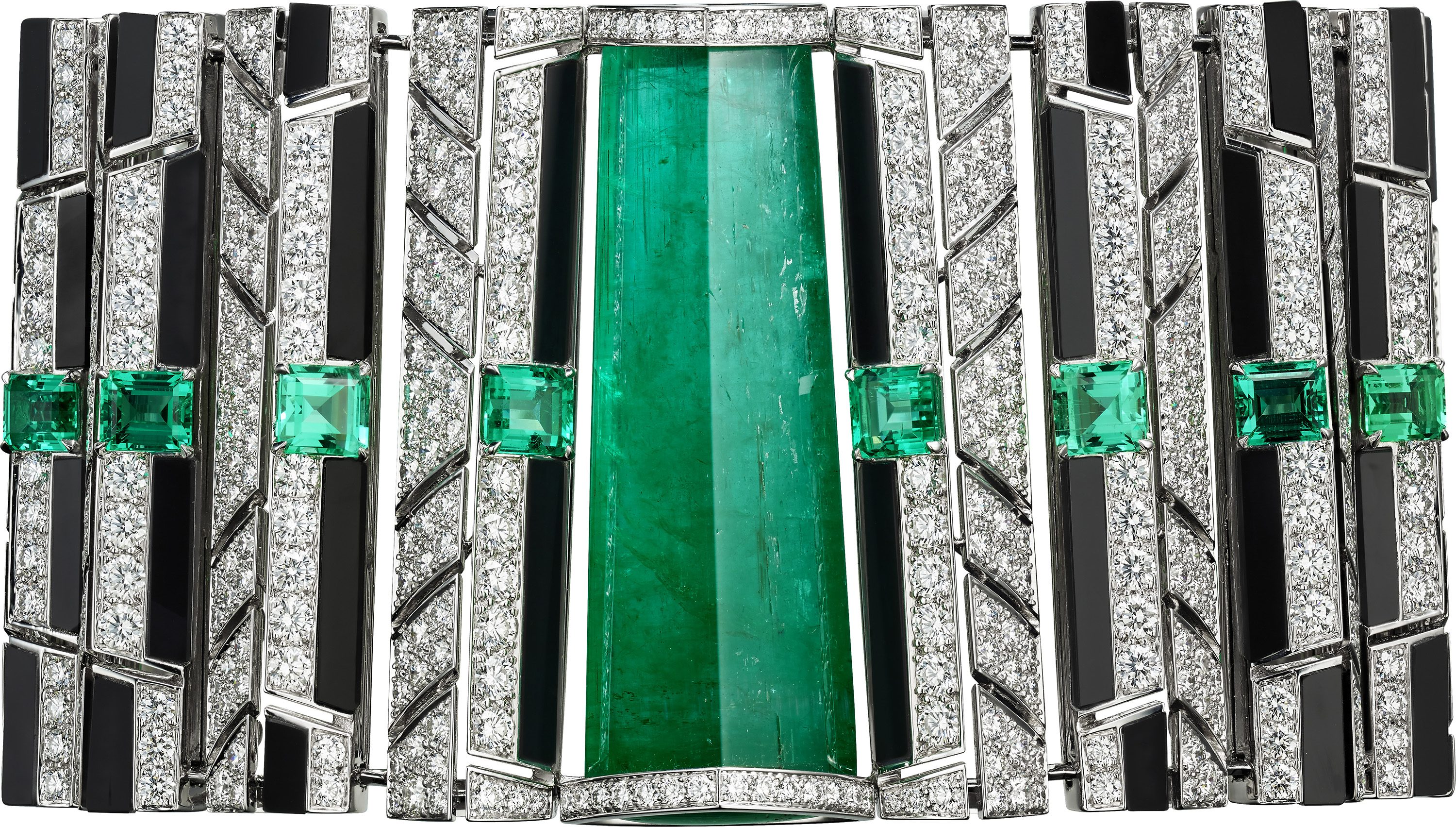

Over the ages, the emerald has played a predominant role in the jeweler’s colour palette. In the 1910s, Cartier combined it with the sapphire, promoting a bold colour contrast for Western decorative arts. The emerald has also been associated with the ruby, coral, and onyx ... This mingling of materials continues to guide the Maison: today, the pairing of emerald with the graphic black of onyx or lacquer has resulted in unexpected kinetic designs.

Cartier also innovates in its choice of emerald cuts: baroque for the necklace created for actress Merle Oberon in 1938 and in a 2018 set; pentagonal for a 1923 pendant brooch; hexagonal with uncommon volume for a 2015 bracelet, and even rough for a ring in 2018 … By breaking from jewelry standards, the Maison offers original designs and inimitable character.

From past to present some of the world’s most beautiful emeralds have sojourned in Cartier’s workshops: the Romanov emeralds belonging to Maria Pavlovna, which were set in a parure for Barbara Hutton; the spectacular Chivor quintet; the emeralds in the Orinoco parure; the gems in the Hyde Park pendant earrings and the Amazonie ring… Although many of these emeralds are of Colombian origin, the jeweler has also raised awareness of more recent sources, such as Zambia, from which remarkable specimens are showcased in contemporary designs.