A Cartier fetish animal since 1914, the panther is an enduring icon that has accompanied developments in society and the Maison’s style through the decades.

The panther has always been a source of inspiration in the arts, especially the decorative arts. Emerging from the African savannah and the Asian rainforests, the wild cat lent its spotted pattern to late-eighteenth-century sack-back gowns and would decorate Empire-style interiors a few decades later. At the turn of the twentieth century, wild cats were a resounding success in the art world, with artists seeking to evoke their power and grace. The sculptors François Pompon and Rembrandt Bugatti, and the painter and sculptor Paul Jouve chose the panther as an object of study, trying to represent it in the most realistic manner possible. They took their easels and spent a great many hours in zoos to faithfully capture the big cat’s various attitudes.

At Cartier, the book Études d’animaux by the illustrator Mathurin Méheut (1882–1958), part of the historical library of the designers and now kept in the Maison’s archives, provides excellent testimony to the jeweler’s interest in animal representations, especially the panther—as we can see by just how dog-eared the pages are that bear images of the big cat.

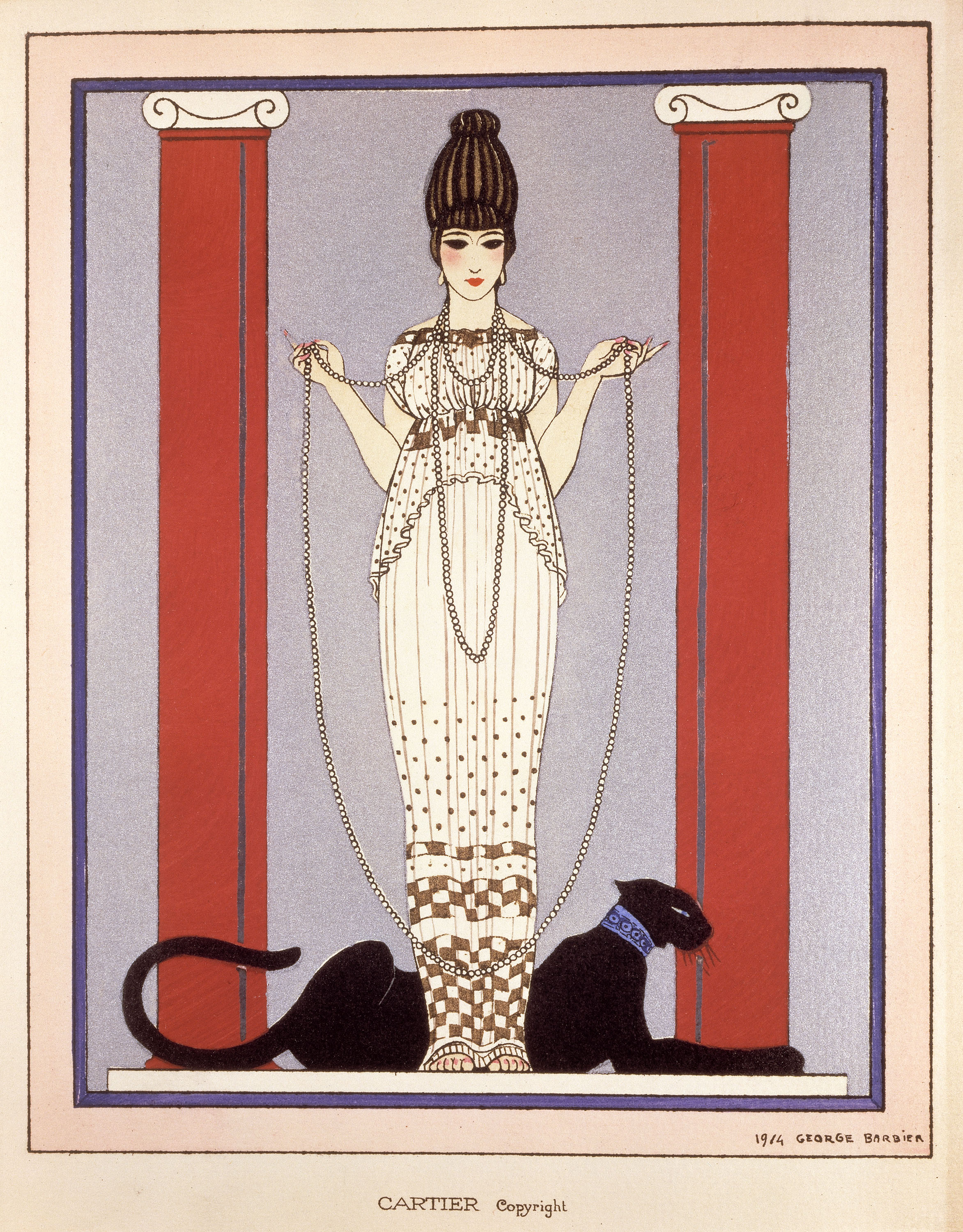

In 1914, the panther’s spotted coat made its debut as rose-cut diamonds and onyx on the case of a women’s watch. This creation was the first representation of the motif in modern Western jewelry-making. That same year, the Maison commissioned the great French illustrator George Barbier (1882–1932) to design an invitation featuring a “lady with a panther” to accompany the display of a collection of pearls and jewelry with an antique theme. This sealed the bond between the jeweler and the feline: the panther-spot motif enjoyed a lively success in the following years in many pieces of jewelry and accessories.

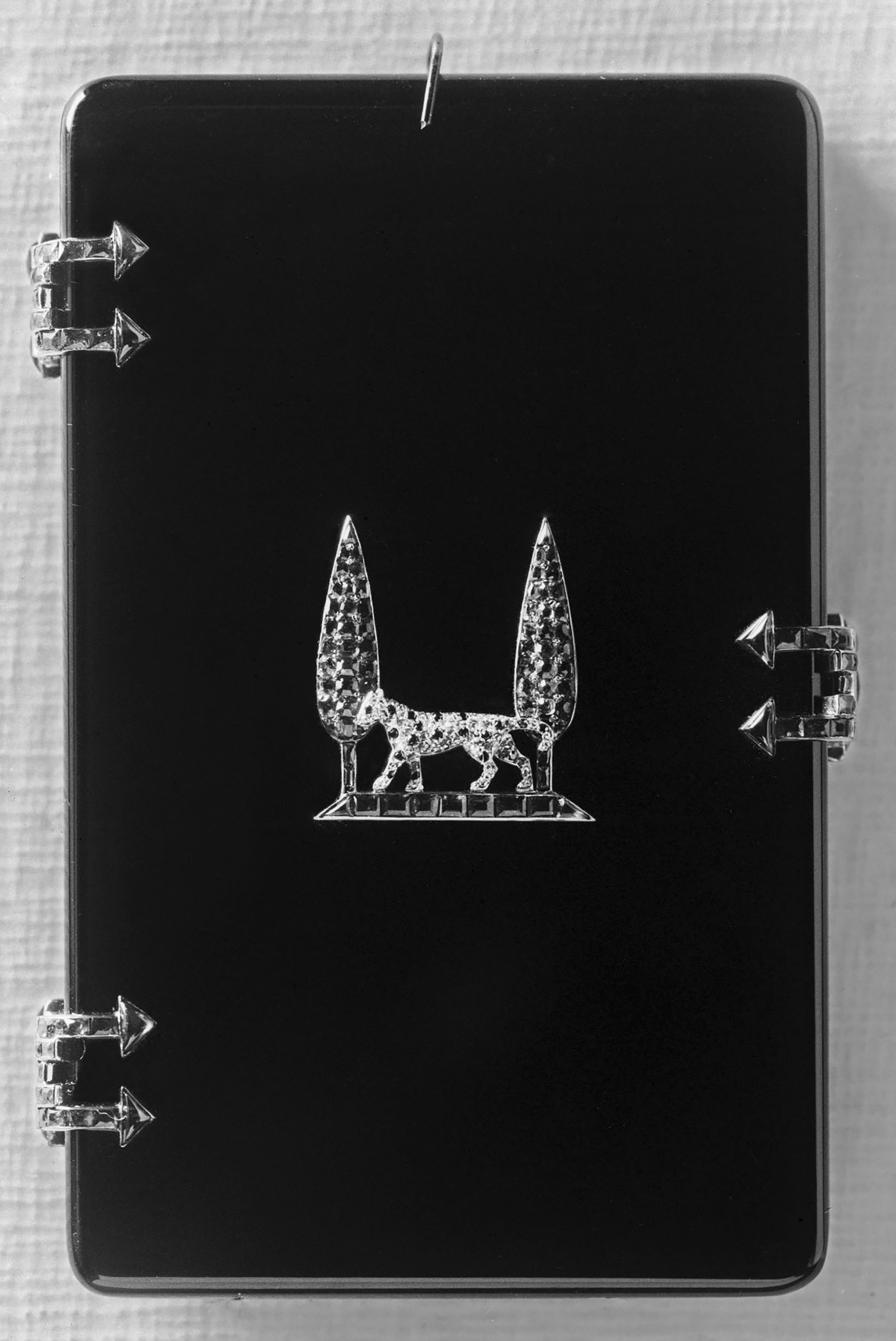

The panther made its first full appearance on a cigarette case in 1917, depicted walking in profile between two cypresses. A gift from Louis Cartier to his friend and future colleague Jeanne Toussaint, this object heralded the destiny of the animal at Cartier under her stewardship. Her attraction to the panther was clearly manifested in both her personal commissions and her stylistic choices for the Maison, where she became Creative Director in 1933. She felt a deep connection with the feline—her nickname was “the panther”—and was committed to making the panther a symbol of independent women.

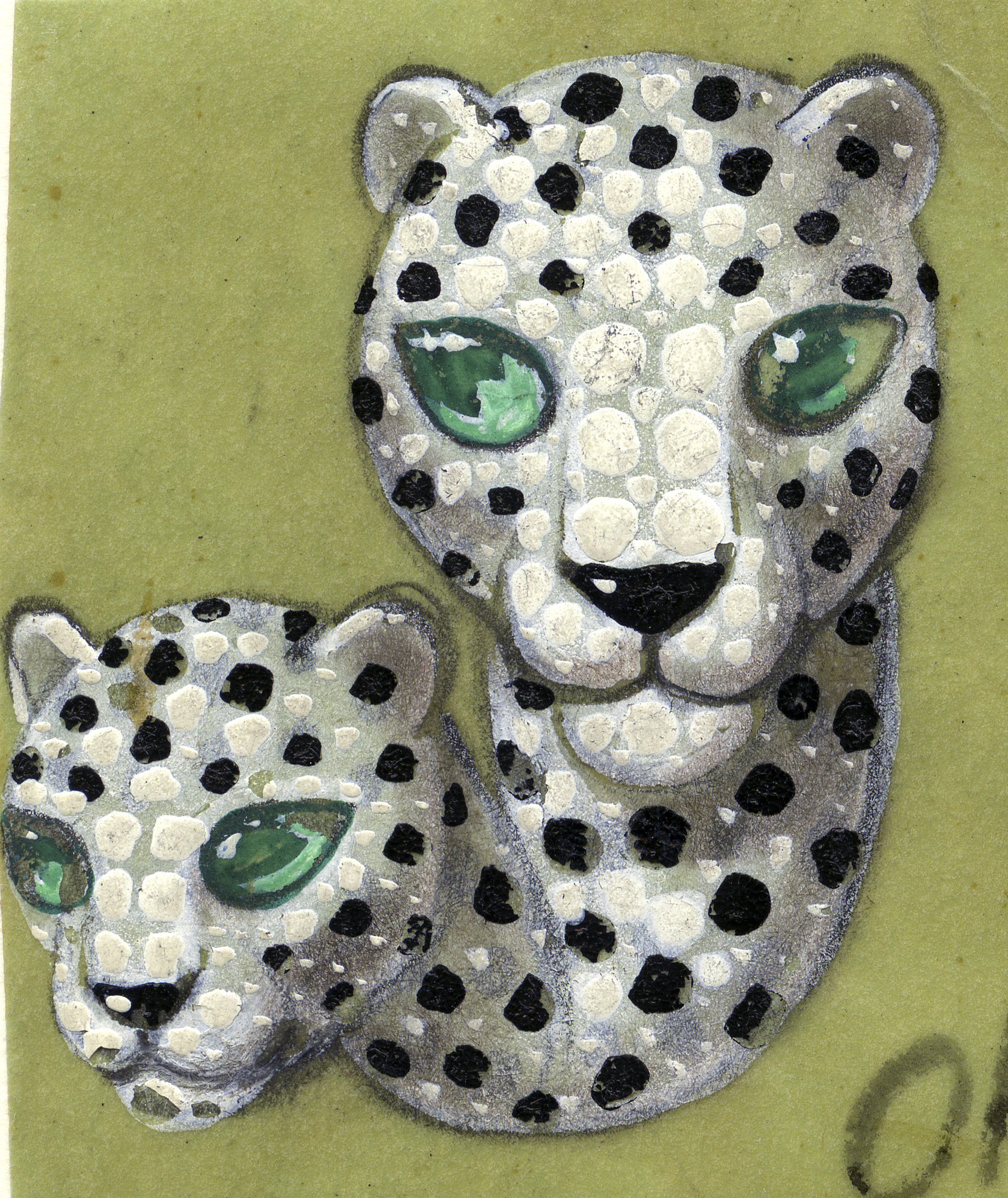

In 1935, the felid was interpreted for the first time in three dimensions for a ring. The upper bodies of two panthers face off in a mirror-image composition with a red-pink sapphire held between their legs. The emphasis on the animal’s muscles also marked a turning point in its representation. Jeanne Toussaint applied herself to give to the panther all its power and vivacity, with the help of the artist Pierre Lemarchand, who rendered the feline in a more sculptural form.

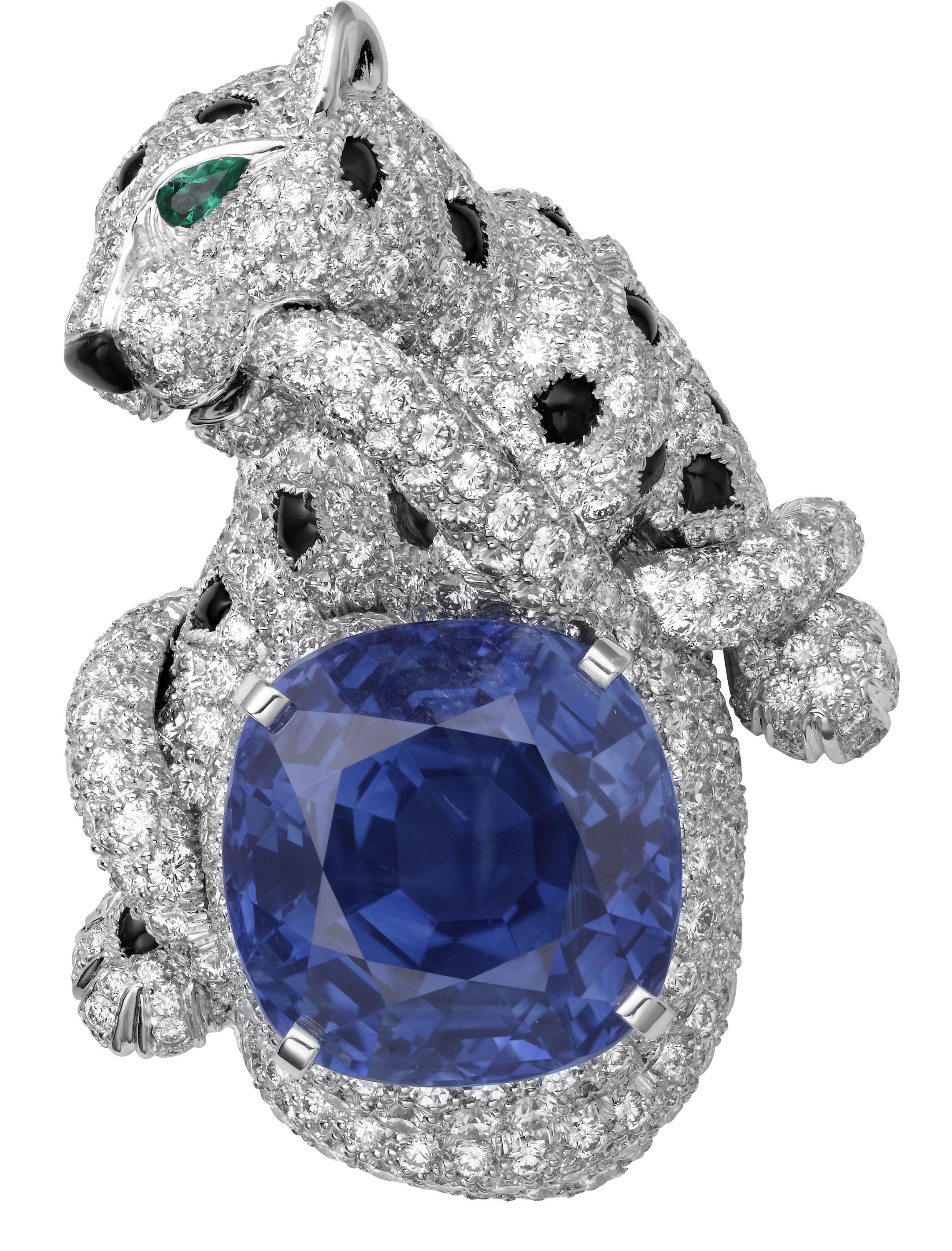

In 1948, a panther in yellow gold speckled with black enamel was featured on a brooch, standing guard over an emerald. This was the first time ever that the panther was shown in its full three-dimensional form. The piece was ordered by the Duchess of Windsor, known for her audacious character. Cartier created another similar brooch one year later, with a cabochon-cut sapphire. Introduced as a stock item by Jeanne Toussaint, the brooch would also be purchased by the Duchess, who had taken the animal as an emblem of her own personality. Other important clients of the Maison would become enamored of it in the following decades, including Daisy Fellowes, María Félix, Marella Agnelli, Nina Dyer and Juliette Gréco. The panther became an alter ego for women, accompanying them toward emancipation, standing as an alluring symbol of liberty.

Now emblematic of the Maison, the panther has gained an unchallenged stature in both jewelry and watches. In 1980, its silhouette was rendered on a brooch in a novel fashion as a double, intertwining Cartier C, with two stylized cats in diamonds, sapphires and emeralds. Three years later, its supple silhouette freely inspired the bracelet of a yellow-gold watch, dubbed Panthère, and would become a reference point in the Maison’s timepiece creations.

The introduction of lost-wax casting in the early 1980s profoundly enriched the panther’s range of expression. Up until then principally made of hammered gold, it could now be sculpted in wax, and then cast in the precious metal. This allowed its anatomy to be reproduced with greater detail, delicacy and naturalism. The innovative use of this time-honored casting technique in jewelry-making opened new paths of expression for the designers: they envisioned the panther in a range of unprecedented attitudes, each one more realistic than the last. Prowling, leaping, watchful, resting languidly, playful, cuddly… The range of postures and attitudes has continued to grow to this day. In 2017, the Résonances de Cartier Collection featured a necklace where the panther is literally plunging into a precious cascade of aquamarines in a scene bursting with life.

Parallel to the naturalist vein, Cartier also explored more stylistic, even abstract, territories for this icon. The panther began to be represented in more forthrightly geometric designs. Its morphology was evoked in a more architectural structure, moving away from the realism otherwise so dear to the Maison. One example is a ring from 2005 crafted in yellow gold, peridots, onyx and black lacquer. The same ring with its snarling mouth was represented in 2014 for a wired architectural composition, found again on La Panthère perfume bottles in 2016. One year later, the panther appeared on a clutch bag, its head outlined geometrically thanks to differently colored facets, like the pieces of a mosaic.

Cartier also continued to develop the panther’s spotted fur motif. Staying true to that first watch of 1914, two rings, made in 2005 and 2008, took stylization a step further. The round spots of the former convey a more sensual idea of the animal, while the more angular ones of the latter evoke its predatory nature. In the new millennium, the animal’s silhouette has progressively dissolved into a pixel-like pattern or metamorphosed into a myriad of precious stones. This abstract aesthetic changed the codes of representation of the feline, as is seen in many collections. For Cartier Royal, presented in 2014, cadenced stylized spots on a bracelet in white gold, onyx and diamonds give a feeling of movement, as if the panther were leaping off the wearer’s wrist.

Naturalistic or stylized, realistic or abstract, 2D or 3D, predator or tender, but always noble, the panther is inseparable from the Cartier style.