The ruby is the red variety of corundum. It is one of the four recognized precious stones, along with the sapphire, the emerald and the diamond. The fiery intensity of its red color, its exceptional vibrancy and its rareness combine to make the ruby one of the most highly coveted gems, which is why it is commonly called the “queen of precious stones.”

- Group: corundum

- Chemical composition: aluminum oxide

- Colour: pinkish red to deep red

- Hardness: 9 (Mohs scale)

- Sought-after origins: Burma, Mozambique, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Thailand

Etymology, myths and legends

Its current name comes from the Latin ruber, which means “red.”

Rubies were known to the Greeks and appear in documents from 315 BCE. In ancient Rome, rubies did not have a distinct name and were included with other red stones, such as garnets, in the generic group carbunculus, named in reference to the red glow of embers.

In his encyclopedic work entitled Natural History, Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) already wrote about the ruby. He highlighted the vigor and brilliance of the gem, of which some specimens were as transparent and pure as a flame.

It would appear to be in India that people first understood that rubies and sapphires were (differently colored) varieties of the same mineral. This fact was demonstrated scientifically at the very end of the eighteenth century. Nonetheless, for many years the ruby would still continue to be confused with the garnet and, especially, the spinel (often called a “balas ruby”).

A plethora of legends about rubies exist. One, taking place in Burma in time immemorial, recounts that the Earth’s largest, oldest eagle flew over a valley one day. Gleaming on a slope was a huge piece of fresh meat. Its color was blood-red. The eagle tried to pick it up, but its talons could not grasp it. After several attempts, at last the bird understood: this was no piece of meat, but a unique and sacred gem made from fire and the very blood of the earth. That stone was the world’s first ruby; the place was Mogok, the legendary Valley of Rubies.

Formation of the stone

Like all corundum, rubies are allochromatic. If pure, the stone is colorless, but this native form is very uncommon. Rubies owe their color to the presence of traces of chromium.

The complexity of the environment and elements that form a ruby explain the gem’s scarceness in terms of both quantity and weight. A ruby of more than 3 carats is a rare find. Above that weight, a stone’s value increases considerably. A high-quality ruby of more than 20 carats can be considered to be an exceptional specimen.

Rubies crystallize in an often relatively compact bipyramidal hexagonal structure.

Origins

A gemstone’s origin is not a guarantee of quality, although it is a recognized criterion in determining its value.

Color indications according to origin are based on assessments made by professionals and observations pertaining to a majority of high-quality stones from that provenance.

It is customary to indicate the country of origin on gemological certificates. The mine location is rarely specified.

Rubies from Burma

For more than 800 years, rubies from Burma were generally considered to be the world’s most beautiful. The best-known mines are those in Mogok, a mountainous region in northern Burma. Rubies from this provenance can be recognized by their rich color, ranging from pink to a very intense red, and the pure redness of the flashes they produce, which resemble embers when the stones are held against the light.

Rubies from Burma often display various types of inclusions, mainly of crystals such as calcite, and sometimes an uneven distribution of color. Needles of rutile, called “silk,” form geometrical patterns and, when slight, give the ruby a velvety look. Rubies from Burma may display other more or less visible inclusions.

As a leader within the luxury sector, Cartier is committed to ensure it applies responsible sourcing practices. As a result, from October 2007 to January 2017, Cartier did not source any ruby from Burma. Since December 2017, Cartier no longer sources any stones from Burma.

Other Asian rubies: from Vietnam, Thailand (Siam), Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Pakistan

Similar in color to rubies from Burma, Vietnamese rubies appeared in the 1980s, but their production quickly became limited.

Thailand has produced relatively dark red, well-formed and intensely brilliant stones, referred to as Thai or Siamese rubies, mainly between the 1970s and 2000s.

Ceylon rubies have a fresh color that can be described as cherry-red. There are very few high-quality Ceylon gems.

Long-known deposits in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan produce very few stones of high quality.

African rubies

In the past few decades, large quantities of magnificent stones have been sourced not only from Asian mines, which for many years exclusively produced the world’s most beautiful rubies, but from the African continent. These new deposits are located along the eastern coast of Africa: in Tanzania, Kenya, Madagascar and, recently, Mozambique. They supply rubies in varying quantities depending on the source, whose best specimens are highly prized and extremely valuable. The Winza mine in Tanzania provides rubies of very high quality, but of very limited quantity.

African rubies have a characteristic orangey-red secondary color, which heightens the gems’ flashes in addition to a relatively intense bluish-red primary color.

Mozambique rubies

Ruby deposits discovered in Mozambique in 2009 and their mining are currently the biggest sources of gem-quality rubies, together with those from Burma.

As is typical of East African gems, rubies from Mozambique develop hues that lean toward both blue (purple base) and yellow (orangey-red fire). The stones are often relatively flat.

Cuts and shapes

The high physical constants of rubies – the hardest of natural gems (along with sapphires) after diamonds – allow for a wide variety of cuts and shapes.

Round rubies and rectangular shapes with step-cut sides (called “emerald-cut”) are rarely seen with weights of more than 1 carat and are hard to find. Most cabochon-cut rubies are oval, occasionally in sugarloaf shape, but other shapes such as pear or teardrop can also be found.

Star rubies are appreciated for the six-pointed star produced by the shimmering needles of rutile they contain. A pure-red ruby with a centered, visible star is a rare and prized find. The bottoms of star rubies are kept unpolished to heighten this asterism.

Pigeon-blood rubies

This name refers to classifications originally introduced by the Burmese in the Mogok Valley, which were based on the color of the blood of various animals. The designation has no scientific basis and describes well-formed rubies of the highest color quality, i.e. neither light nor dark, with no sub-tint. These stones are exceedingly rare.

The use of this term by many laboratories should be considered with care. There are no purely rational criteria enabling a ruby to be classified as pigeon-blood; when it appears on a certificate, the term should be understood as no more than the opinion of the issuing laboratory.

Care recommendations

Although very hard, rubies are vulnerable to impacts, which can cause chips or even a break. Like all precious substances mounted in jewelry, rubies must be handled with care.

Ultrasonic treatment is not safe for rubies.

Cartier and the ruby

From past to present, the ruby has held a special place in Cartier’s stylistic journey. Although it first appeared only occasionally, the ruby has played a star role since the 1920s, especially in Indian-inspired creations.

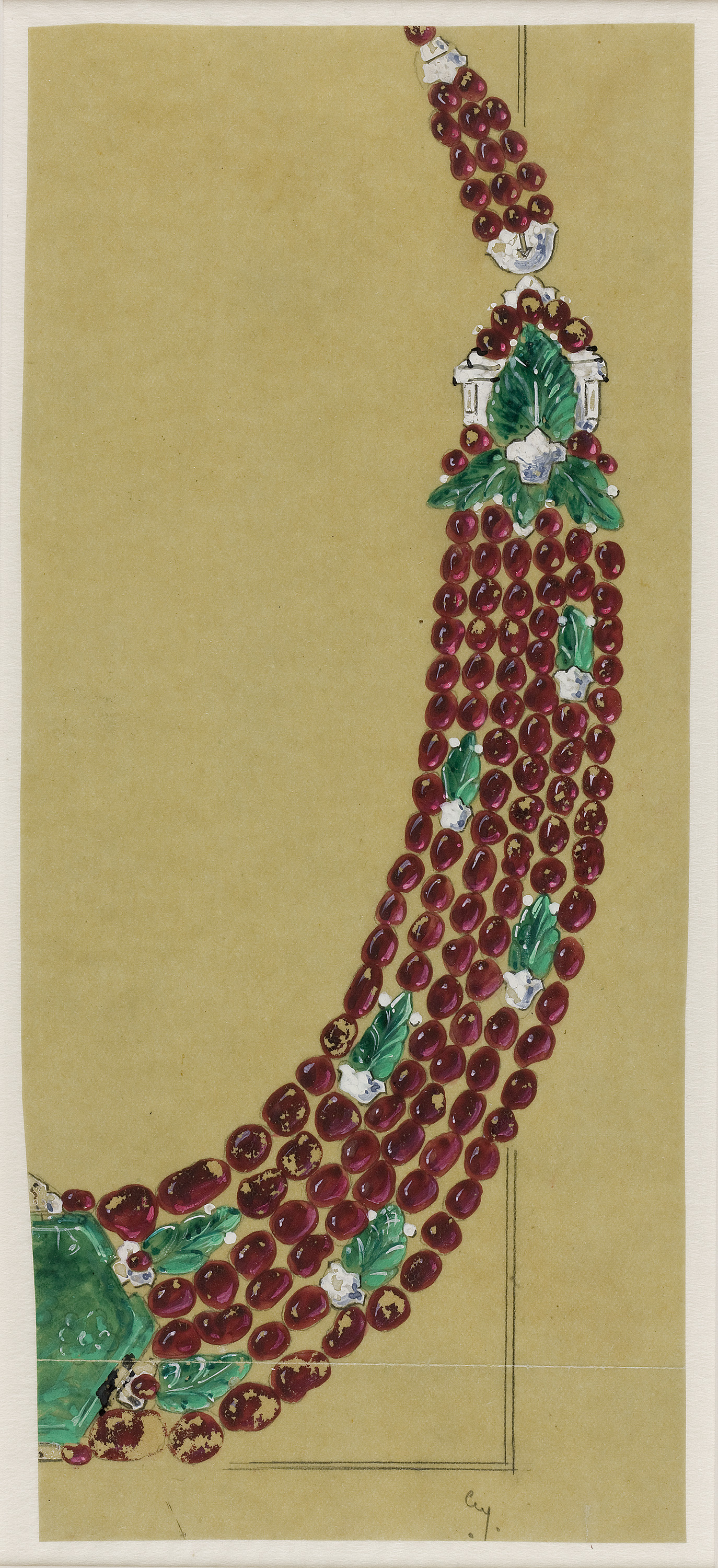

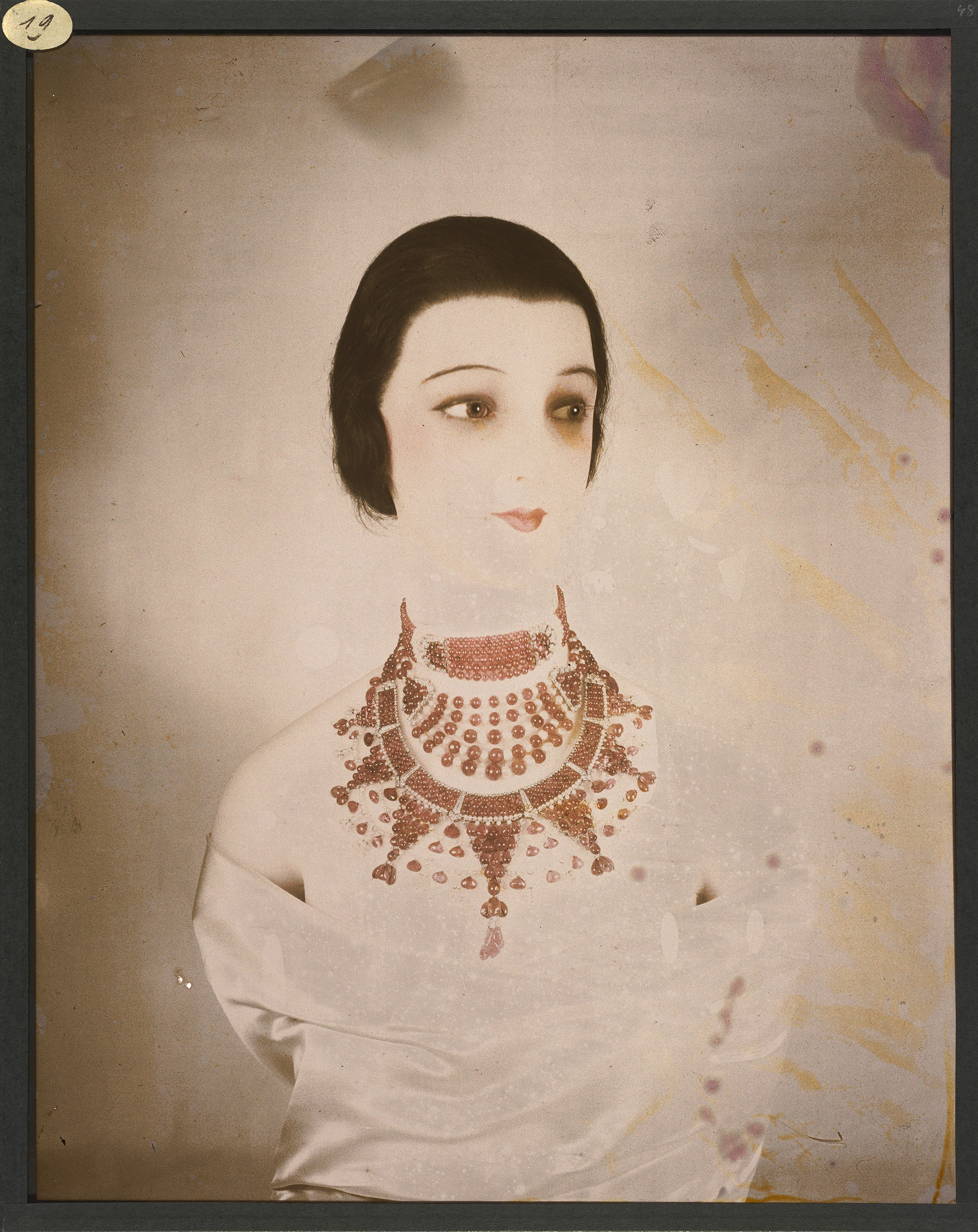

As a demonstration of wealth and symbol of power, the ruby was a favorite stone of maharajahs. They rivalled one another in the wealth of their collections, counting myriads of gems among their treasures. The rarest and most coveted rubies, those that distinguished the most eminent monarchs, originated from Burma. Several of these sovereigns brought their gems to Cartier to be magnified in beautiful settings. In the 1930s, Jam Sahib Digvijaysinhji, the Maharaja of Nawanagar, entrusted no fewer than 119 Burmese rubies to the jeweler. From this exceptional assortment, the Maison imagined a strikingly modern necklace, whose structured design of baguette-cut diamonds reflects that era’s taste for geometric looks.

Around the same time, Cartier received an equally spectacular order from the Maharaja of Patiala: a composition of three necklaces for one of his wives, the Maharanee Bakhtawar Kaur Sahiba. Inspired by traditional Indian jewelry, the design bridged the gap between the West and the East while introducing elements of Art Deco. It was also a feminine counterpart to the ceremonial jewelry of maharajas.

In the wake of World War II, while the naturalistic style enjoyed a revival, Cartier released rubies from the confines of ceremonial attire, incorporating the gems into delicate, elegant pieces. Featuring arabesques, scrolls and so on, the designs had a classic spirit but offered flowing volumes. Jewelry gave even more allure to elegant women, such as Lady Deterding, who ordered a suite of rubies adorned with palmette motifs in 1951; Elizabeth Taylor, who was given a necklace, a pair of pendant earrings and a bracelet, all set with rubies and festoons of diamonds, by Michael Todd in 1957; and Princess Grace of Monaco, who wore three ruby and diamond clips on a tiara for her official portrait. As clusters of small beads in yellow-gold settings, rubies also graced rings and bracelets of a more accessible luxury during that time.

Inspirations from Indian ceremonial jewelry and sensual femininity combine in exceptional contemporary creations, such as the Reine Makeda necklace. In this design presented in 2014 at the Biennale des Antiquaires de Paris, a spectacular cascade of diamonds streams from a 15.29-carat ruby from Mozambique.

Truly a queen gem, the ruby is also majestically presented as a central stone. The Pourpre and Fleur de Lotus rings come to mind, which magnificently showcase very rare 10.17-carat and 8.38-carat specimens, respectively, from the legendary Mogok mine in Burma. Clean lines, subtle geometric play, dazzling effects ... This “nothing in excess” reveals the essential: the splendor of rubies.