Cartier, always interested in other grand civilizations, developed an early passion for Egypt. Pharaonic architecture, amulets, scarabs, and papyrus flowers have been enlivening Cartier’s stylistic repertoire for over a century.

Early contact with the kingdom of the pharaohs

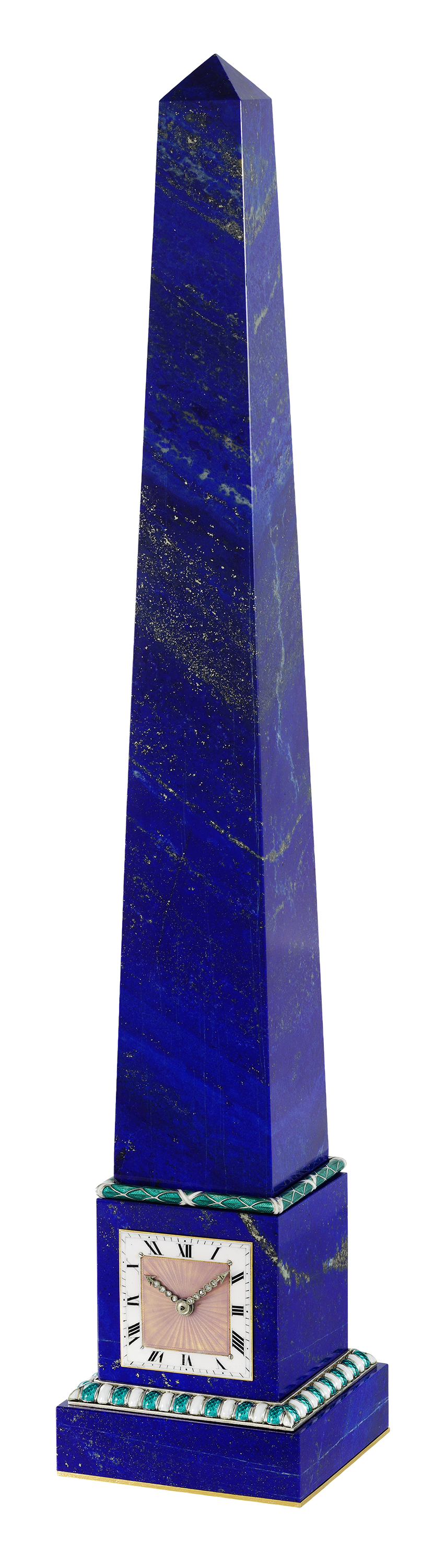

French infatuation with Egypt dates back to Napoleon Bonaparte’s military and scientific campaign there in 1798, and lasted throughout the nineteenth century, notably thanks to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. The ancient civilization on the Nile served as a major source of inspiration for the arts in general, and for fashion and the decorative arts in particular. In the realm of jewelry and timepieces, Cartier earned a reputation for its sophisticated designs, such as an 1873 châtelaine adorned with medallions showing four frontal heads of pharaohs wearing the Nemes headdress that symbolized their power. Another key Egyptian motif adopted by Cartier is the obelisk. Its slender shape, pointing proudly skyward, was perfect for certain decorative objects such as a thermometer made in 1906 and a clock made in 1908, both of which employed carved hardstones in wonderful harmony with refined enamel work.

Despite a Franco-Egyptian exhibition hosted by the Louvre in 1911, interest in Egypt went on the wane. But Egypt never disappeared from Cartier’s ledgers, for at the dawn of the Art Deco period the jeweler boldly evoked that influence in a more stylized way, by playing on geometric shapes and color. Such was the case, for example, of a 1920 clip-brooch, made of sapphires, coral, onyx, and diamonds, whose graphic design was freely based on the flabellum, a traditional fan composed of peacock feathers or lotus flowers attached to a long handle.

Egyptomania in the 1920s

The widely publicized discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in November 1922 revived Western curiosity about ancient Egypt. Europeans and Americans thronged to the Valley of the Kings in order to admire pharaonic remains that influenced fashion designers, architects, writers, and jewelers.

Eschewing a fancifully exotic image, Cartier stood apart from its counterparts by conscientiously respecting Egyptian architecture and iconographic repertoire. Pyramids, porticos, pylons, columns, lotus flowers, papyri, hieroglyphs, and friezes of hieratic profiles were emblematic motifs that Cartier designers copied into their sketchbooks during visits to the Louvre or while reading the books on Egyptology supplied to them. This inspiration proved highly fertile, for Cartier offered its clients a wide range of items—evening bags, accessories, and clocks decorated with scenes seemingly taken straight from the walls of a pharaoh’s tomb, plus “Sudanese” or “Egyptian” bangle bracelets, and brooches in the form of a temple or an oasis, not forgetting jewels decorated with lotus flowers or stylized papyri etched in fine lines of black enamel. New noble materials were also employed, such as lapis lazuli, woven into original color combinations that were perfectly synchronized with the Art Deco trend of the day.

Cartier’s authentic attachment to Egypt was capped in 1929 when the Maison was granted a warrant of official supplier to King Fuad I. That same year, Cartier participated in the French Exhibition in Cairo, where it displayed several pieces of jewelry.

A new life for antiquities

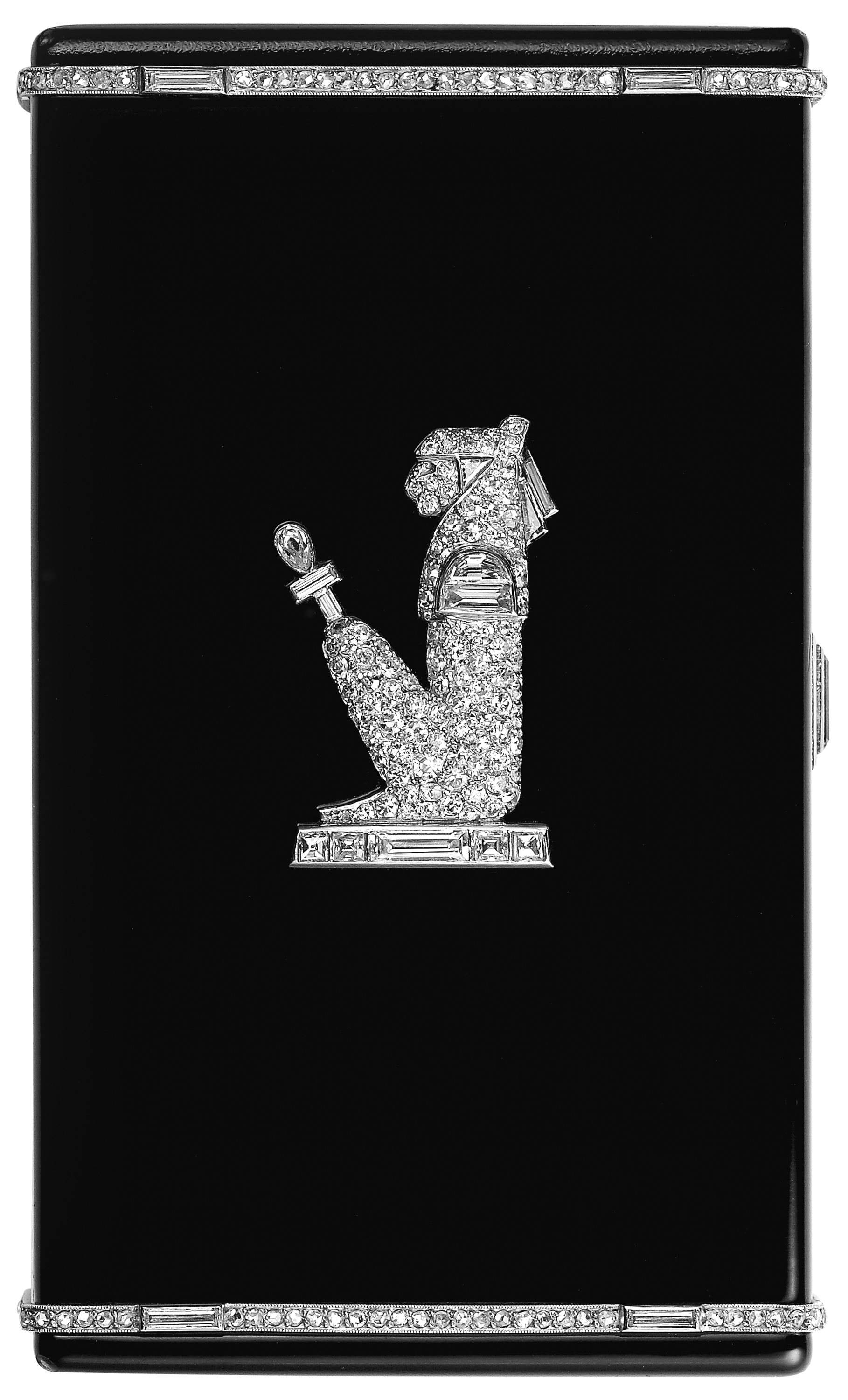

In the Egyptian vein, Cartier has been noteworthy above all for its original designs that incorporate fragments of ancient objects, listed as apprêts in the ledgers. Louis Cartier himself was an enlightened collector who, starting in the 1910s, acquired age-old artifacts from specialized dealers, in particular Kalebdjian and Dikran Kelekian, whose galleries on Rue de la Paix and Place Vendôme, respectively, were not far from his own premises. His frequent visits there often resulted in the purchase of small objects such as amulets and statuettes of gods, known in ancient Egypt for their talismanic properties. A blue faience scarab, probably used in a funeral rite to ensure that the deceased would be resurrected in the afterlife, thus became the central motif of a belt buckle; a small sculpture of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet was used on a brooch; a figurine set in a plaque of lapis lazuli—a lucky charm in its day—henceforth adorned a vanity case.

These modern settings underscore the value of archaeological vestiges all the more for respecting the patterns, colors, and visual codes of ancient Egypt. By way of example, the vanity case mentioned above, made in 1924, was etched with hieroglyphs accurately copied by Cartier artisans from the titulary of Pharaoh Thutmose III.

Egyptian influence on contemporary design

The Egyptian theme reached a peak in the late 1920s. While it was certainly more understated in subsequent decades, it continued to surface in exceptional items, such as a halo-shaped head ornament of 1934 that featured lotus flowers, and a clip-brooch of 1966 in yellow gold, coral, turquoise, and diamond that depicted a profile of a pharaoh crowned with a pearl. Above all, color combinations inspired by Egyptian antiquities—such as lapis lazuli with turquoise—survived by extending themselves into many other spheres of Cartier’s work.

In 1988, Cartier devoted a whole line of jewelry to the realm of the pharaohs. Their heavy pectoral necklaces were reinterpreted as women’s jewels in which yellow gold was boldly contrasted with white gold. Animal motifs predominated on matching sets of jewelry adorned with friezes of panthers and on necklaces bearing scarabs either clutching a turquoise or flaunting wings pavé-set with diamonds.

The beetle, henceforth emblematic of the Cartier bestiary, made a much-noted reappearance on a brooch in 2000: geometric lines evoking printed circuits and constrating material gave birth to a new, bionic animal that, on the threshold of the new millenium scrutinized the future.

When it comes to recent design, Egyptian influence is reserved for the most glamorous pieces. At the 2008 Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris, Cartier displayed an obelisk clock no less spectacular than its predecessors made in the early twentieth century. Composed of carved stone, rock crystal, and mother-of-pearl, it was embellished with a statuette of the god Osiris dating back to the 30th dynasty (380–342 BCE). Still in the realm of fabulous clocks, Cartier created a sensation at the 2017 Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie in Geneva with a bracelet-watch featuring a rare group of thirty-two emeralds set on a mount whose shape imitated a papyrus flower. Even as it flaunted its Egyptian inspiration, the design insisted on a resolutely abstract freedom of interpretation. This timeless item created a bridge not just between the ages but also between civilizations.