The archives are a unique reference source on the Maison’s history and design right from the very beginning.

The three departments of archives reflect Cartier’s expansion abroad, with the opening of a first branch in London in 1902 and another in New York in 1909. They thus record local production of the Maisons in London and New York as well as Paris. Several types of documents are carefully preserved in these archives.

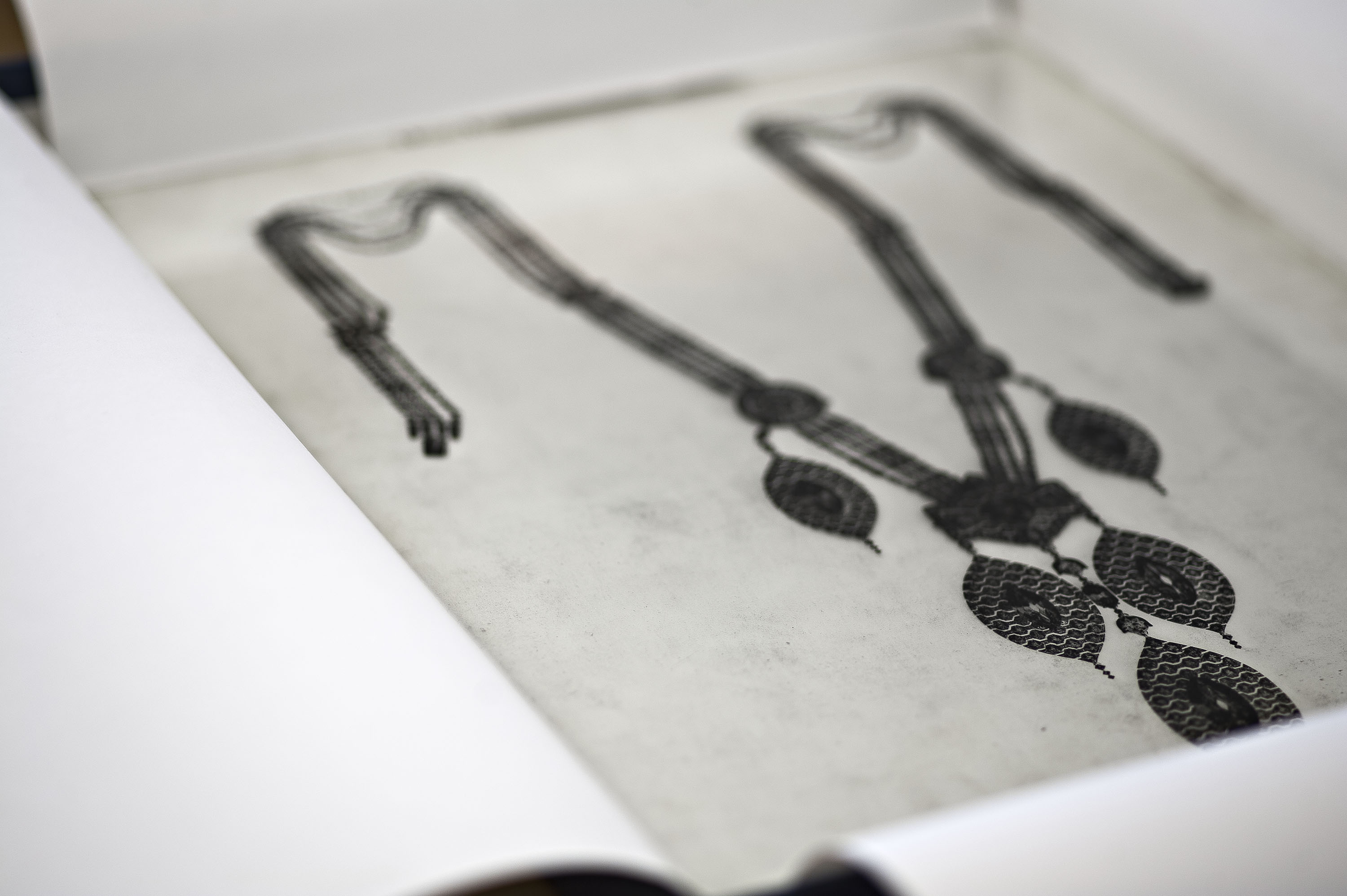

To begin with, the drawings: from initial rough sketches to finished execution drawings, the archives boast extremely rich visual material. Designs were traditionally drawn on tracing paper and colored in gouache, details being underscored in graphite. Items were always drawn life-size, a crucial requirement in so far as artisans would rely on the drawing to bring the jewel to life.

The archives sometimes point further back, to the very source of inspiration. Indeed, the Maison has kept the notebooks in which Louis Cartier and his designers recorded ideas, sketches and creative notes. The notebooks bore evocative titles such as “idea book” and “new ideas.”

They now enable us to grasp the creative process employed in the past. Included, for example, are not only references to the Musée Guimet, where the designers often went to look at Oriental artworks, but also certain publications that provided inspiration. Indeed, Louis Cartier had acquired numerous books on the history of art and architecture, which he placed at the disposal of his designers, spurring their creativity and enlightening them on various ancient or distant civilizations that might fuel new designs. This library is still conserved by the Maison.

Cartier began using photography as early as 1901. A photographer was hired by the Maison to document jewelry as soon as it left the workshops. Although only major pieces were selected at first, by 1907 everything was being photographed. As with the drawings, the rule was that photos must be life-size in order to document the pieces with the greatest accuracy. In addition to this wealth of visual material that helps to understand the development of the Maison style, a collection of negatives sheds light on the evolution of photographic techniques. The Paris archives, for example, boast nearly 40,000 glass-plate negatives (with a silver-bromide gelatin emulsion) as well as a fine collection of Autochrome plates, the ancestor of color photography (which became standard at Cartier in the 1980s with the extensive use of Ektachrome).

Older pieces were sometimes cast in plaster as well as recorded photographically. These casts were made from finished jewels, providing a unique, three-dimensional record of Cartier designs. Conserved in Paris at the Rue de la Paix premises, the casts look like raw jewelry stripped of its precious gems—an almost archaeological vestige of certain jewels that no longer exist, because lost or later disassembled.

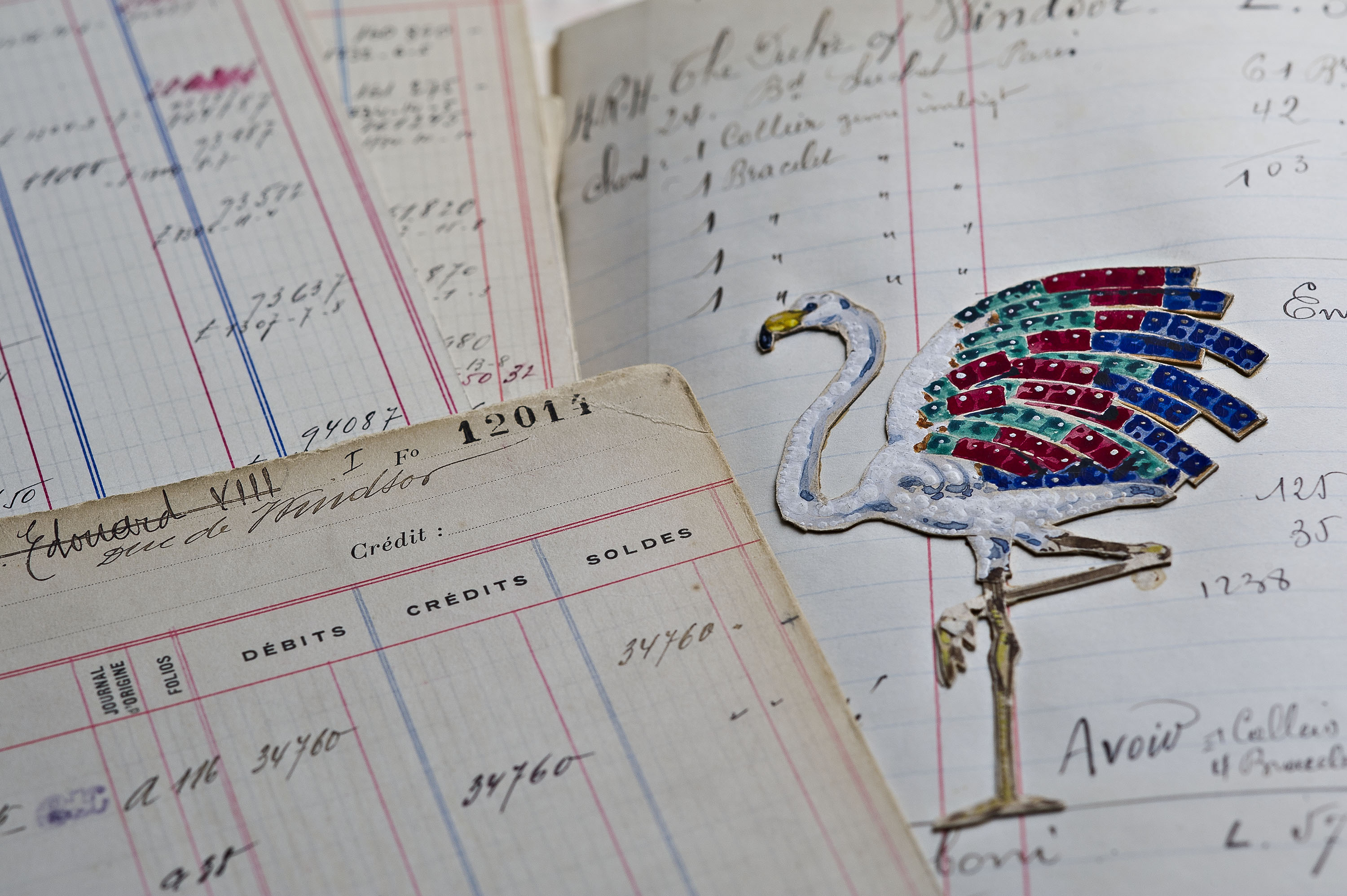

Finally, the archives contain Cartier’s account books: stock ledgers, order books, sales ledgers, client accounts and so on. Every piece made in the past is individually described with precision, from the day it left the workshop to the moment it was sold. These ledgers provide information on the exact date an item was finished (corresponding to the date of delivery by the workshop) as well as an accurate description and, above all, a detailed list of its components. They also record the details of sales; and it is because they contain information on clients that these particular archives remain confidential and off-limits to the public. Only material related to design and production can be consulted, internally, by house designers or by experts assessing old jewelry that resurfaces on the art market. Like a catalogue raisonné of an artist’s oeuvre, these archives not only confirm the authenticity of Cartier jewelry but also guarantee its value on the art market.