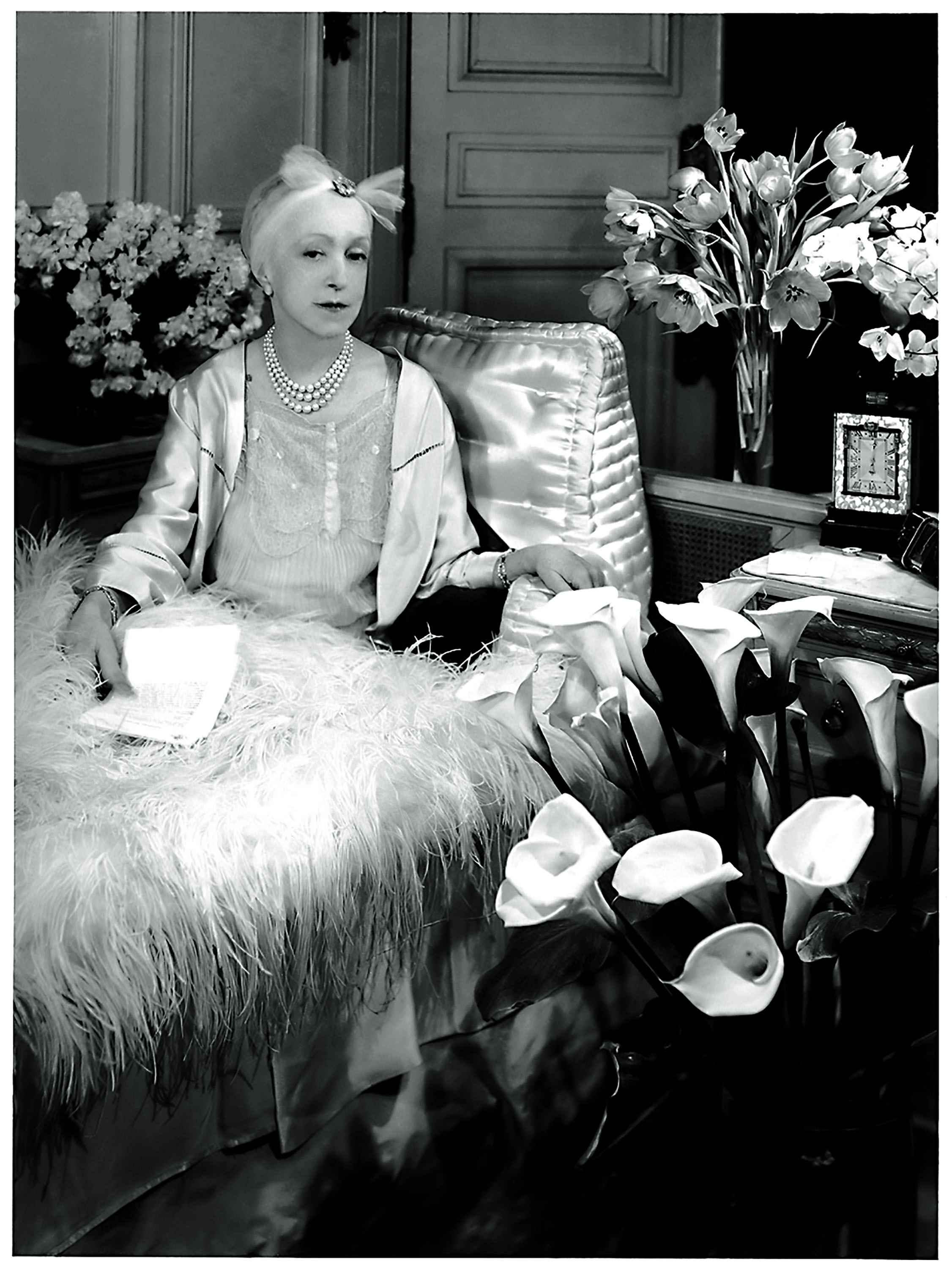

Elsie de Wolfe (1865–1950), pioneering American interior decorator, was a woman of character, boldly affirming her choices throughout her life, even when they came up against the conventions of the time. A woman of taste, sensitivity and refinement, she was a devoted Cartier client.

Elsie de Wolfe, née Ella Anderson de Wolfe, was born on December 20, 1865 in New York. The daughter of a doctor, she grew up in an affluent household complete with private tutors and high-society gatherings. At the age of 17, her parents sent her to Scotland to live with her mother’s family. There, she came into contact with British high society, and was even introduced to Queen Victoria in 1883.

Elsie returned to New York the following year and developed a passion for theatre, enthralled by the work of young amateur theatre companies. In 1890, she had to cope with the death of her father, an inveterate but unlucky gambler, who left her nothing more than heavy debts. Rather than looking to marry some rich suitor, Elsie made a daring choice for her time: she decided to go to work. Driven by her love for the stage, she envisaged becoming a professional actress and realized her first successes thanks to the support of a friend, the impresario Elisabeth Marbury. Their friendship soon metamorphosed into something more intimate. Transgressing established customs and scandalizing New York high society, the two women set up house together in 1892 in a residence on Irving Place. Elsie took charge of the decoration. She did not hesitate to replace the furniture and drapes to suit her tastes. She painted the walls a sober beige or other pale tones and installed large mirrors and chaises-longues… Comfort above all—a revolutionary concept at the end of the nineteenth century.

Much impressed, those close to Elsie urged her to give up theatre and dedicate herself to interior decoration, a profession up to then the exclusive domain of men. Her social connections, as well as her much acclaimed interior design for the Colony Club—opening in 1907 as the first women-only private club—allowed her career to develop quickly. Morgan, Frick, Vanderbilt, Condé Nast, all the New York elites clamored for her services. Her reputation also spanned the Atlantic: in 1938, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor commissioned her to decorate the Château de la Croë on Cap d’Antibes.

Now retired from her acting career and fully committed to interior design, Elsie de Wolfe was constantly sought after, whether for the renovation of a villa or for decorating advice, and she had the idea of writing a book for a broad audience. Published in 1913, The House in Good Taste was an immediate bestseller. An entire generation of Americans were influenced by her modern vision of décor, which may be summed up in four principles: uncluttered space, light colors, luminosity, comfortable furniture.

Dividing her time between the United States and France, Elsie was a key figure admired as much for her good taste as for her eccentricity. A woman of character and independent spirit, she surprised everyone by marrying Sir Charles Mendl in 1926. Already rich and famous, at the age of 60 she obtained something that she still lacked: a title. With her husband, Lady Mendl hosted sumptuous parties at Villa Trianon, a country house not far from Versailles that she had purchased and remodeled at her own expense in the early 1900s. In 1938 and 1939, she gave two balls, among the most sought-after events of the day, in homage to her friend the fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli.

Elsie de Wolfe certainly admired Parisian Haute Couture, but she was even more taken by the fine jewelers. A loyal Cartier client, she would cultivate this passion throughout her life with innumerable purchases: an aquamarine tiara, necklaces, medallions, brooches, a three-gold bracelet, as well as timepieces, evening bags, an automobile console and other refined accessories. More than a taste for luxury, Elsie de Wolfe and Cartier shared a similar vision of elegance and style.