Cabochons have been a hallmark of the Maison’s style for over a century, whether highlighted as a central feature, applied to the crown of a wristwatch, or as an embellishment on a precious accessory.

An ancient cut, emblematic of Cartier

The word “cabochon” describes a gemstone that is polished rather than faceted, usually round or oval, flat underneath, and with a domed top surface whose curvature can vary in depth. If the stone is of especially conical shape, it is called a “sugarloaf”—a type of cabochon that is especially prized among connoisseurs. Although the cabochon dates back to ancient times, it has never ceased to spark the interest of jewelers throughout the ages.

Cabochon-cut stones have held a significant place in Cartier’s stylistic vocabulary for over a century. Probably inspired by Russian jewelry, the Maison first used them on decorative enamel objects in the early 20th century, applying cabochon-cut sapphires to highlight the lines of a design or to embellish the corners and clasps of ladies’ nécessaire.

A signature jewelry touch

From that period on, Russian-influenced timepieces also began to be set with cabochons. They were used to adorn clocks as well as the crowns on pocket watches and necklace-watches. Cabochons also featured on bracelet-watch designs from around 1906, as well as on some of the earliest models of the Tonneau watch. The cabochon soon became a signature jewelry touch on Cartier timepieces. Following the launch of the Tank watch in 1919, the cabochon-cut sapphire became a recurrent and characteristic adornment on the Maison’s watches.

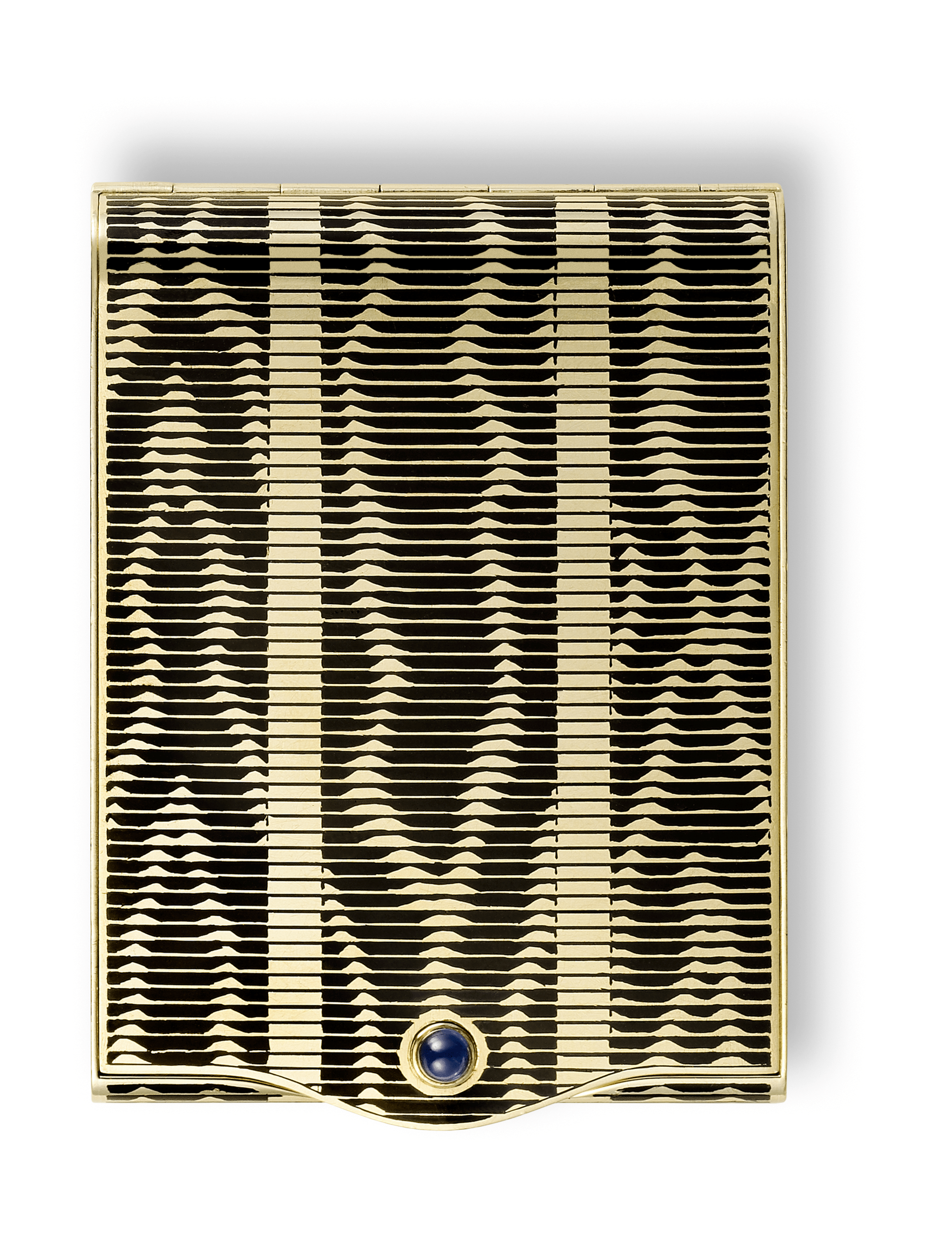

Throughout the 1920s and ‘30s, cabochons were also an embellishment of choice on accessories. Crowning pens and razors, adorning cigarette cases and handbag clasps, they added a jeweled touch to Cartier objects.

The Cartier cabochon, past and present

In the jewelry of the 1910s and the subsequent Art Deco period—which Cartier helped usher in—faceted and calibrated stones were much in evidence, and these were instrumental to the pared-down aesthetic that was then in vogue. Round shapes, especially cabochons, would occasionally be set as center stones; they add a certain tension, injecting dynamism into pieces of primarily geometrical design. They were also widely used in novel chromatic compositions. Applied in little accents, emeralds, rubies, onyx and all kinds of fine gemstones served to heighten the Maison’s new color palettes, which were bright, but balanced.

Cabochons were also especially favored for pieces inspired by the world’s different cultures, a very popular theme of that era. The organic aspect of cabochons made them well suited to the Maison’s compositions of colored stones reminiscent of India (later baptized Tutti Frutti), to interpreting Asian motifs like Chinese vases or the phoenix, and for dotting Persian-influenced designs.

From the 1930s on, Cartier went in for figurative design again more than ever. Cabochons were the first choice for pieces inspired by flora and fauna. Jeanne Toussaint, who was appointed creative director in 1933, liked using them to render the bodies of birds, a favorite theme of hers as much for their symbolism as for their design possibilities.

She also showcased round stones, in a more stylized register, on very sculptural pieces. Cabochons—in rich profusion, in a wealth of colors, of ample volume, and often combined with the sunny gleam of yellow gold, were ideal for generous, architectural compositions that nonetheless retain a sense of fluidity and are comfortable to wear.

Cabochons feature in many of today’s designs, ranging from tributes to the Maison’s stylistic heritage to new, contemporary interpretations. They may be foregrounded on High Jewelry rings, combined in rich abundance on the naturalistic pieces in the Cactus collection, or dotted across boldly graphic Neo Art Deco designs.