A member of the corundum family, the sapphire is one of the four recognized precious stones, along with the ruby, the emerald and the diamond. Although sapphires exist in every hue of the rainbow, the name used alone without specifying color only denotes the blue variety.

- Group: corundum

- Chemical composition: aluminum oxide

- Color: from deep blue to light blue

- Hardness: 9 (Mohs scale)

- Sought-after origins: Kashmir, Burma, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Madagascar

Etymology, myths and legends

The name sapphire appears to derive from the Sanskrit word saniprya, which evolved into sappheiros in Greek, a term that seems to have also designated lapis lazuli.

In ancient Egypt and Rome, the sapphire was considered to be the sacred stone of truth and justice. In various cultures, it also symbolized stability and strength.

Formation of the stone

The combination of intense color and exceptional vibrancy make the sapphire one of the most sought-after and employed gems in jewelry.

Corundum is allochromatic: in pure form, the stone is colorless, but this native form is very uncommon. The sapphire owes its color to traces of titanium and iron. The combined presence of these two elements in the stone produces its specific hue.

The sapphire is found naturally in a hexagonal bipyramidal structure that is more or less elongated, ending in a point or a flat surface.

Origins

A gemstone’s origin is not a guarantee of quality, although it is a recognized criterion in determining its value.

Color indications according to origin are based on assessments made by professionals and observations pertaining to a majority of high quality stones from that provenance.

It is customary to indicate the country of origin on gemological certificates. The mine location is rarely specified.

Many sapphire mines around the world have been explored for centuries, such as those in Burma and Ceylon, or, in more contemporary times, those in Kashmir, Thailand, Cambodia, Australia and even the United States. Even more recently, deposits in Africa have been mined: in Tanzania, Nigeria and, the latest addition, Madagascar. Of all these origins, Cartier gives precedence to those producing the highest quality gems.

Sapphires from Kashmir

A rich, warm color and a remarkably velvety aspect make the sapphire from the Kashmir region (presently India) an exceptional gem. Certain specimens display a very slight, characteristic blue-green tint which, in soft touches, increases the value of the stone (the famous Kashmir green).

Discovered in 1881 or thereabouts, these sapphire deposits are located at an altitude of over 4,500 meters, in a mountainous region of the Himalayas, and were intensively mined for only about twenty years, and then explored relatively sporadically until the middle of the twentieth century. The mines are reportedly depleted and the stones currently circulating are “pre-owned,” meaning that they are or have previously been mounted in a setting.

Sapphires from Kashmir may contain growth bands of various crystals, such as zirconia, tourmaline and feldspar, intersecting in a herringbone pattern; fingerprint-like fluid inclusions; and healed fractures (natural recrystallization inside an inclusion). Sapphires from Kashmir do not contain rutile.

Sapphires from Burma

Extracted from the Mogok mines, Burmese sapphires are appreciated for their deep, vibrant blue. Their color is even, with very little growth zoning. The most frequently seen inclusions are silks (small mineral needles of rutile) of varying density, negative crystals (following the contours of an included crystal that has since disappeared), and healed fractures (natural recrystallization inside an inclusion).

As a leader within the luxury sector, the Maison is committed to ensure it applies responsible sourcing practices. As a result, since December 2017, Cartier no longer sources any stones from Burma.

Sapphires from Sri Lanka

Mining dates back to Antiquity; the term Ceylon (the former name of Sri Lanka) is still used to designate sapphires from the country known as the “Resplendent Isle.” For centuries, this small island south of India was the source of the largest production of gem-quality sapphires.

Specimens with this origin typically display light saturation and sometimes an electric hue. Ranging from cornflower blue to a very pale blue, in pure colors, with a slightly violet tint that is especially visible in electric lighting, these sapphires are said to be mainly unearthed near the city of Ratnapura (literally “the city of gems”).

A wide diversity of inclusions characterizes Ceylon sapphires. The most frequently encountered types are butterfly wings (fluid inclusions made up of small wing-like drops that intersect and evoke the insect), negative crystals, silk and colorless zones.

Sapphires from Madagascar

In 1998, the first sapphire mine in Ilakaka, in the south of the island, was inaugurated. The stones were mostly fancy colored but also blue. Since then, Madagascar has become the world’s biggest producer of gem-quality sapphires. Stones are buried almost everywhere in its subsoil, and sapphire mines are located all over the island. Gem-quality specimens are found in large quantities in Madagascar, featuring a wide variety of qualities, ranging in color from very light to very dark. Some of their characteristics are similar to those of Kashmir sapphires.

Cuts and shapes

The high physical constants of sapphires – the hardest of natural gems (along with rubies) after diamonds – and their relative abundance, from pavé stones of a diameter of a tenth of a millimeter to cabochon or faceted sapphires weighing more than 100 carats, allow for a wide variety of cuts and shapes.

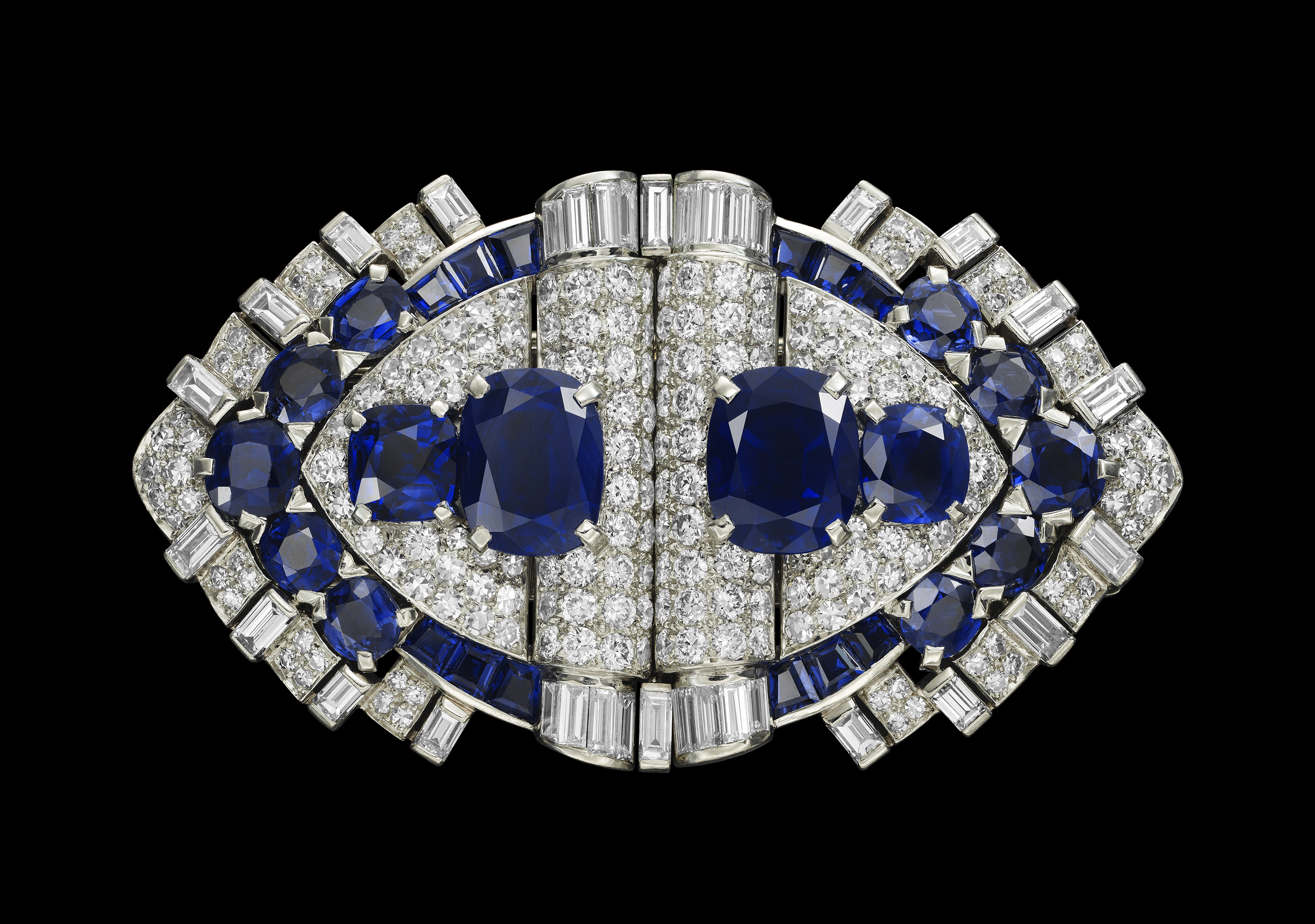

Due to the structure of rough corundum, lapidaries prefer oval and cushion shapes, the latter being especially favored for its elegant look. Sapphires are well-suited to be cut as cabochons, especially in a sugarloaf, but also teardrop or any other shape. Conversely, round sapphires and rectangular specimens with step-cut sides (called “emerald-cut”) are rare, especially if the stone weighs more than one carat.

Star sapphires are appreciated for the six-pointed star produced by the shimmering needles of rutile they contain. A pure-blue sapphire with a centered, visible star is a rare and prized find. The bottoms of star sapphires are traditionally kept unpolished.

Care recommendations

Although very hard, the sapphire is vulnerable to impacts, which can chip or even break a stone. Like all precious substances, sapphires must be handled with care. It is recommended to bring sapphire jewelry to a Cartier boutique for regular cleaning to avoid improper handling.

Ultrasonic treatment is safe for sapphires.

Cartier and the sapphire

As one of the four precious stones, the sapphire emerged early on as a favorite stone at Cartier. For more than a century and a half, it has appeared frequently in the Maison’s registers, which relate encounters of exceptional specimens and illustrious owners.

Some of the most celebrated stones having sojourned in the jeweler’s workshops, those whose exceptional qualities rival their prestigious provenance, are, naturally, the Romanov sapphire, that spectacular 478-carat gem acquired by the Queen Marie of Romania, and the cabochon from the 1949 panther brooch belonging to the Duchess of Windsor. Magnificent specimens also grace contemporary designs: the Cornflower Blue and the Andaman sapphires, which were, respectively, set in a ring for the 2014 Biennale des Antiquaires de Paris and in a necklace the following year, combine all the virtues of remarkable gems.

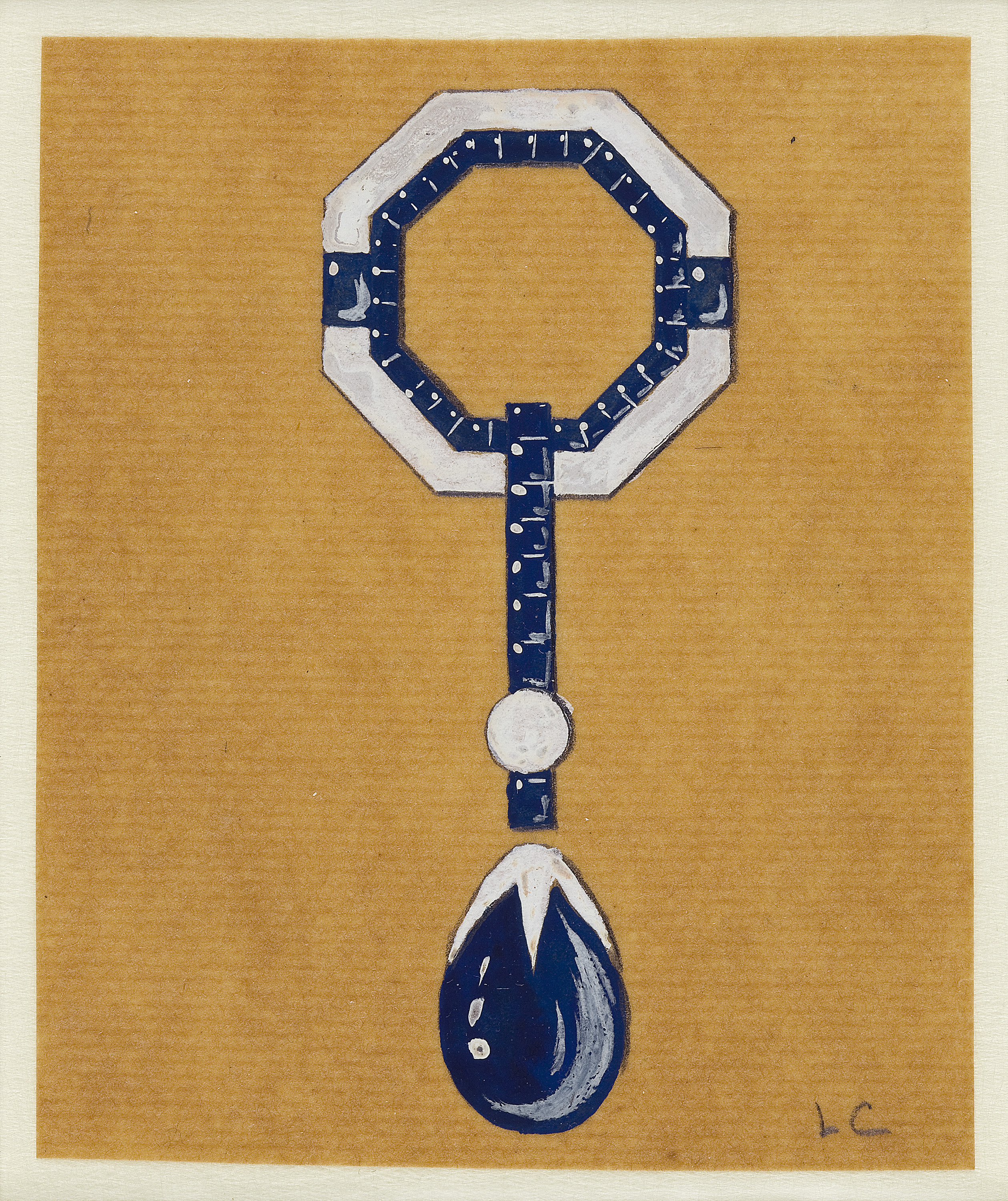

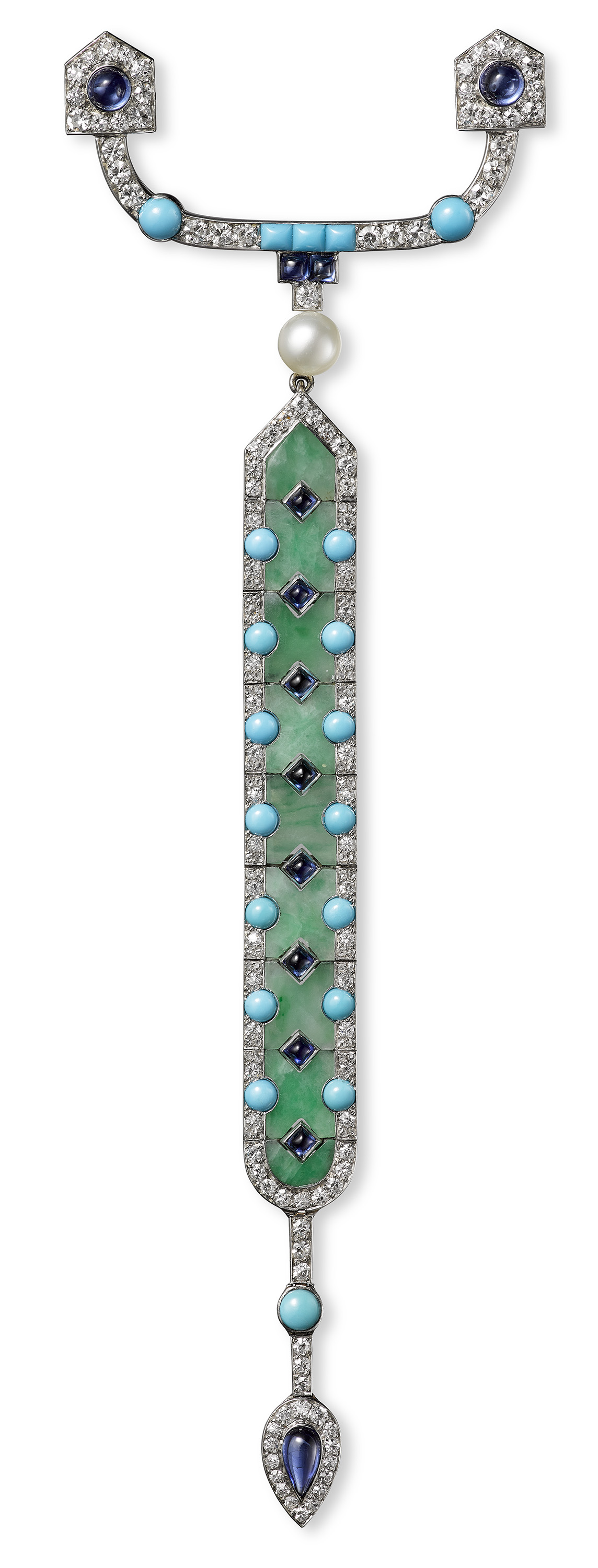

In addition to majestically showcasing these queen stones in special-order designs, Cartier is known for its distinctive use of sapphires in two unique ways. The first involves color palette. As of the early years of the twentieth century, the Maison boldly mingled sapphires and emeralds – or more rarely jade – to introduce a fresh mix of hues that had never been seen before in Western jewelry. Called the “peacock pattern,” this color combination did not initially appeal to the tastes of the time but quickly gained immense popularity and has since become a Cartier classic.

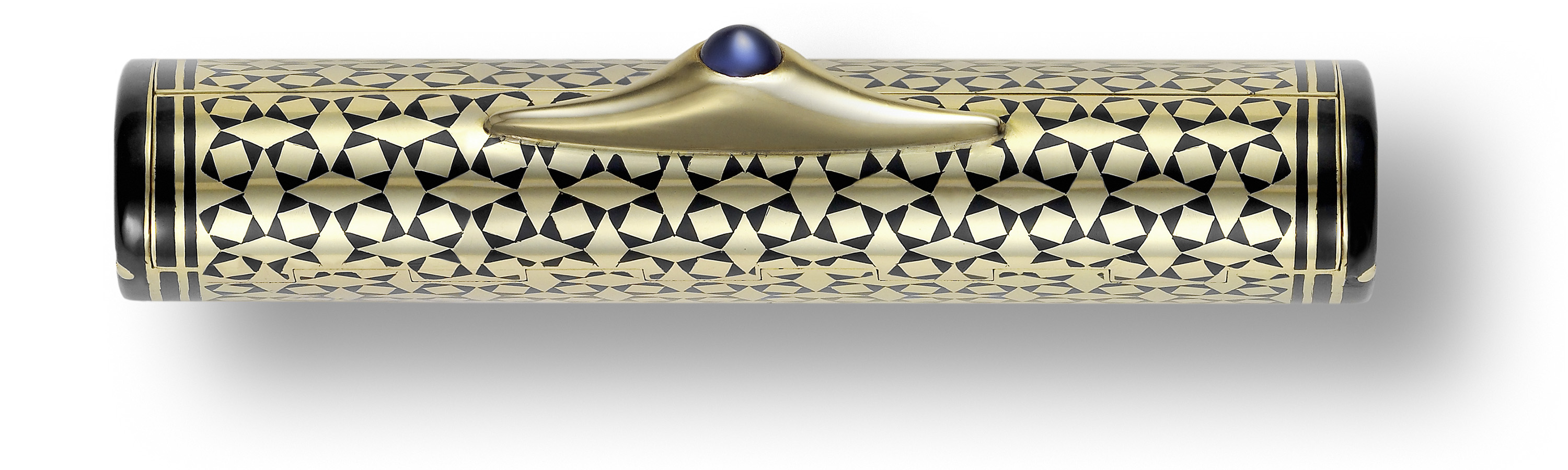

Cartier’s play with sapphire cuts is another distinctive feature. Each of the many cuts in the Maison’s repertoire is associated with an iconic look. As cabochons, sapphires add volume to jewelry, accentuate countless women’s accessories and adorn watch winders. In square or baguette cuts, they heighten the geometry of abstract designs, from the first modern style pieces to today’s understated creations. When sculpted and carved into leaf, bud and plumb berry shapes, it forms part of the trio of gems to be eternally associated with Tutti Frutti.